Emeritus adj (from verb) to earn, deserve, serve

–Webster’s

When Henry Steiner ’55 and Detlev Vagts ’51 published the first edition of “Transnational Legal Problems” in 1968, the collaboration marked a milestone in the field of international law. The casebook, currently in its fourth edition, is widely regarded as the leading compendium of materials for scholars and students in the field. “Together, [Steiner and Vagts] exemplify a commitment they placed on the first page of their joint casebook and reiterated in every edition thereafter,” said Professor David Kennedy ’80 in a recent testimonial: “‘The inescapable decision in the contemporary world is to participate in the life of the international community.'”

Steiner’s focus has been predominantly on human rights, and a huge part of his continuing legacy will be the law school’s Human Rights Program, which he founded. Vagts, too, has been an outspoken proponent of human rights, but he is also one of the world’s foremost experts on transnational business problems and the laws affecting international commerce.

This summer, the two colleagues shared another milestone: retirement from the Harvard Law School faculty. In tribute to these teachers, who served on the faculty for a combined 89 years, the Bulletin asked two of their former students and protégés for summations of these two extraordinary careers.

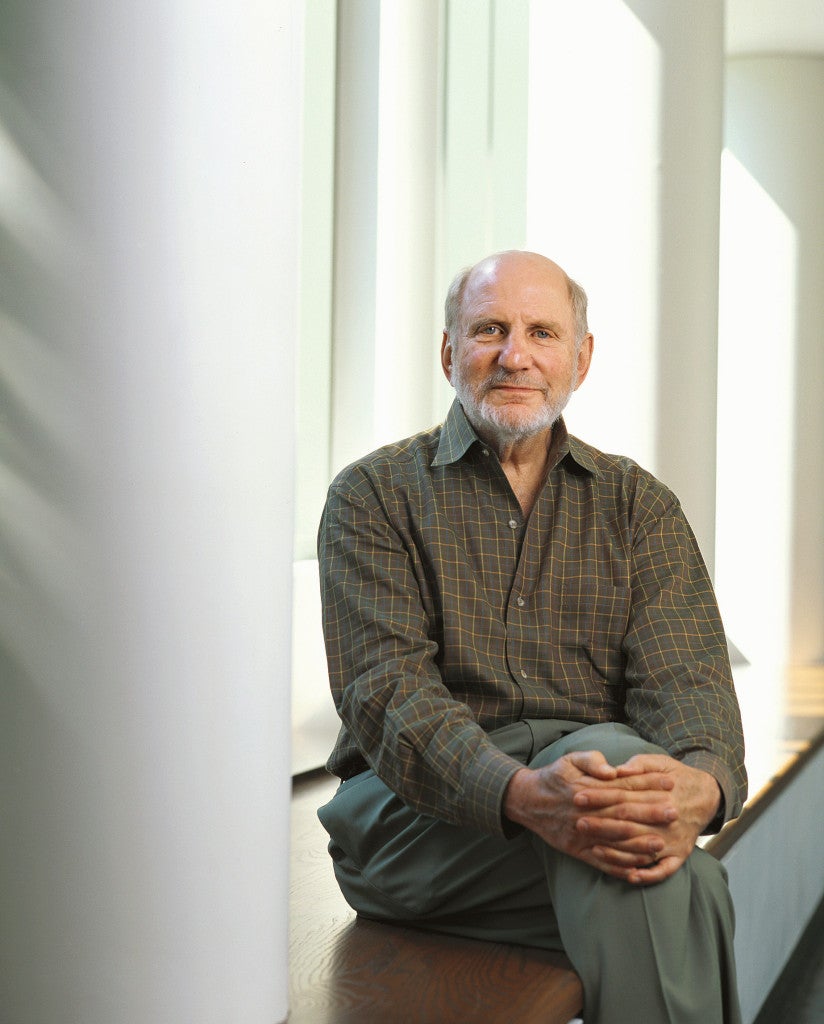

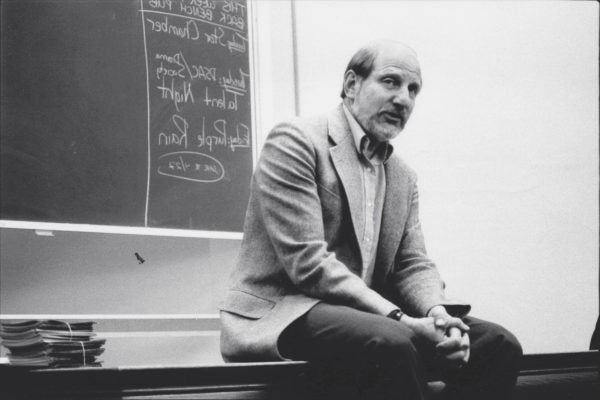

Henry Steiner ’55

Pioneer, scholar and mentor

by Makau Mutua LL.M. ’85 S.J.D. ’87

Today, the power and language of human rights are ubiquitous. But this was not always the case, even a scant two decades ago. This is an idiom whose ubiquity is the direct result of a select few men and women who have dedicated their lives to its propagation. There is no doubt in my mind that Henry Steiner must be counted among them. Because of his singular vision and dedication, the Human Rights Program–now a leading forum in the field–has transformed legal education at Harvard Law School.

I first met Henry in 1984, the same year that a sketch of a human rights program was barely off the drawing board. Little did I know that this Harvard professor with a patrician bearing would carve out a significant niche at the law school for arguably the most critical idea of the modern era. But he did so, and with such a powerful imprint that it is impossible to imagine the law school today without HRP.

Henry believed, almost from the start of the program, that since human rights involves a language of power–of material for battle by the powerless–its legitimation in hallowed institutions was essential to its success. But he also knew that such a program in the academy had to meet exacting standards of excellence. That is why he emphasized HRP’s academic mission. It was on this pillar that all the program’s activities were built: coursework, research, internships, speaker series, visiting fellowships, clinical work and the Harvard Human Rights Journal. Henry correctly believed that HRP was above all a place for academic inquiry.

As a teacher, Henry challenged his students–myself included–to understand human rights as a discipline and to dare question its orthodoxy. Although he holds fast to its humanist and political ideals, Henry has never taught human rights as a religion. Even so, he has often revealed a belief that, far from being an antidote to human catastrophes, the study of human rights can offer a glimpse of the good society. It is this duality of the believer and the skeptic that has allowed Henry to mentor a wide and diverse college of students. These range from the most bracing Third World critiquers of human rights discourse to the most unabashed advocates of the ideology of human rights.

Henry’s book written with Philip Alston, “International Human Rights in Context: Law, Politics, Morals,” captures the open texture with which he approaches human rights. There are no sermons in it. Instead–and this is why I think the book will long remain the standard–he refuses to succumb to the mentality that the classroom is a congregation, and the law school a church. There is much to stir the mind of the idealist and to inspire the student to reach for a higher human intelligence. To achieve that combination is both Henry’s enigma and enduring identity.

Henry has a seductive mind and the wit of a comedian. But his penchant for excellence is unparalleled. Although he has been a mentor of mine–and I credit him with a selfless guidance of my career as a law professor and human rights scholar–he has never himself ceased to be a student. This is one of his most admirable proclivities. He is forever learning, pushing himself to understand other cultural milieus, to better comprehend the complexity of our universe. In August 2003, at an international conference on a truth commission in Nairobi, Kenya, he seemed to learn as much as he gave back. I know this will not change.

HRP would not have been possible without the foresight, commitment and hard work of this deeply complex man. He took a possibility and made it into a reality. There is nary an important human rights institution across the globe that is not inhabited by a person who has been touched by Henry or HRP. That legacy can only grow further, even as HRP enters a new phase. In the academy, he leaves a more expanded political space in which the voices of dissent are less likely to be viewed as wild and dangerous. He has legitimized the difficult question in human rights circles.

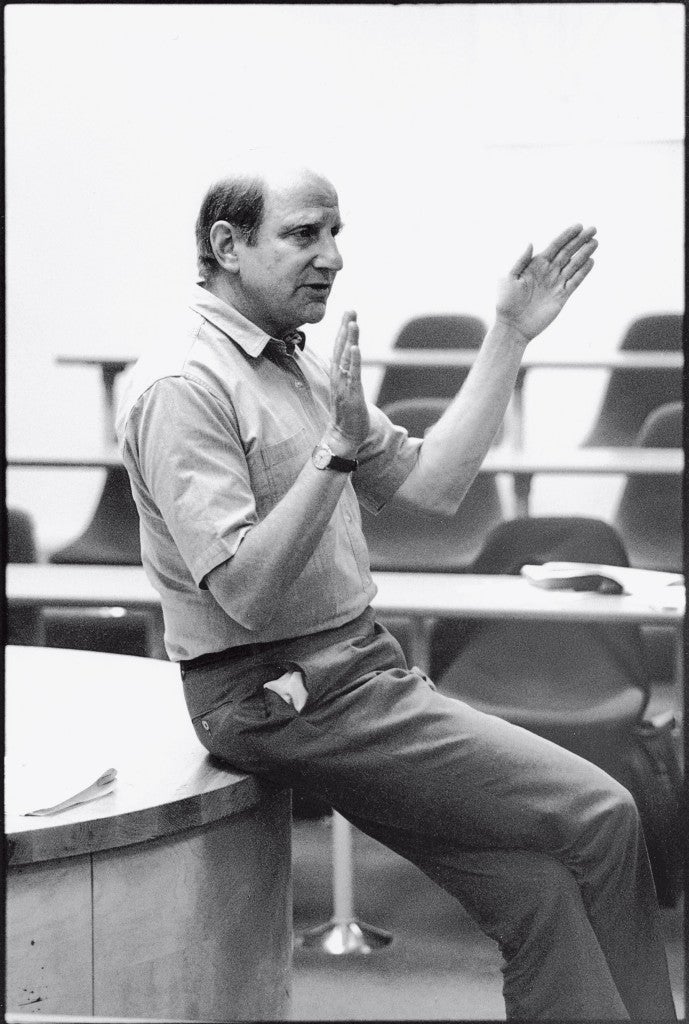

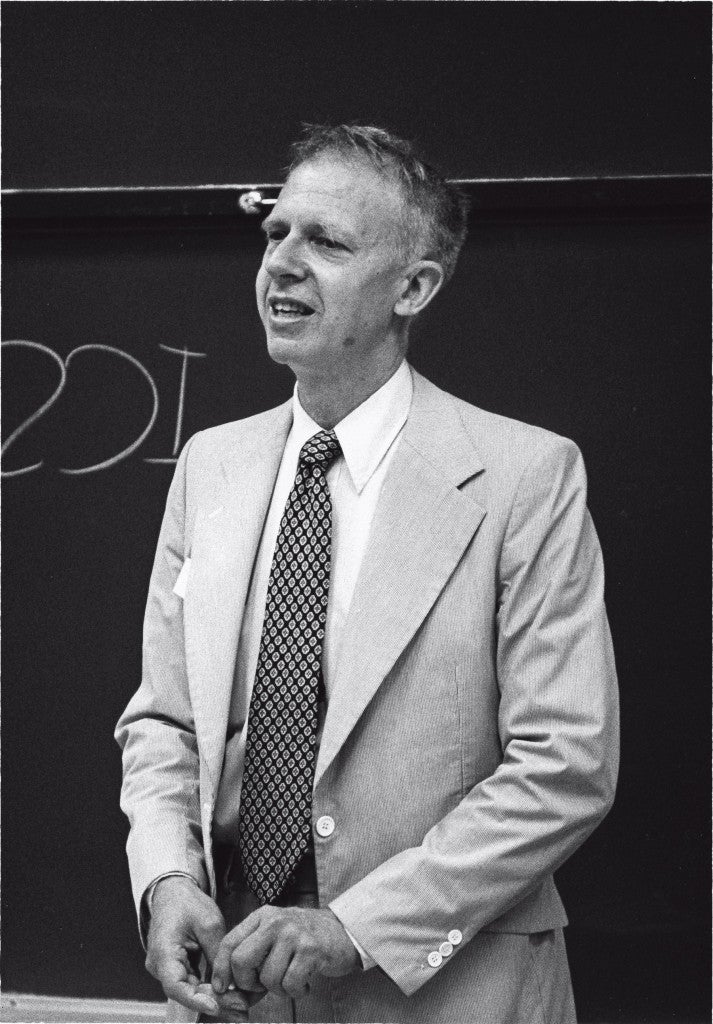

Detlev Vagts ’51

Reflections on the retirement of a gentle giant

by Pieter H.F. Bekker LL.M. ’91

I was privileged to be a student of Detlev Vagts’ while I was obtaining my master’s degree and to work with him as his research assistant after graduating in 1991. Several years later, Vagts served on my Ph.D. committee at my alma mater in the Netherlands. Consequently, I feel myself to be in a good position to attest to the legacy of this gentle giant.

Vagts’ career at HLS spans a whopping 46 years, a half century in which the law school underwent many changes. Having received his education at both the college and the law school, he is truly a “Harvard man.”

Born of an American mother and a German father who fled Nazi Germany, Vagts grew up in Washington, D.C. After his graduation from HLS in 1951, he entered private practice with Cahill Gordon & Reindel in New York City. He sometimes reminisced about his days on Wall Street in his Corporations class, predicting his students might be confronted with this or that question in their offices overlooking the Hudson River in the wee hours of the morning. I remembered this when I had that very experience as a fledgling attorney in New York.

Vagts was recruited by HLS the old-fashioned way. One day, he received a call from Dean Griswold inviting him to join the faculty. And so he became an assistant professor of law in 1959 and received tenure in 1962. He has been Bemis Professor of International Law since 1984.

The breadth of Vagts’ expertise is truly amazing, ranging from public international law to comparative lawyering and professional responsibility, and from international business transactions to securities regulation and corporate law. He has co-written two coursebooks from which teachers and students will profit for many years to come: “Transnational Legal Problems” and “Transnational Business Problems.” In a legal world that has come to be dominated by specialization, Vagts has managed to remain a formidable generalist.

Vagts’ articles have also contributed greatly to legal thinking. “The International Legal Profession: A Need for More Governance?” (American Journal of International Law, 1996) has been particularly influential. It addresses problems pertaining to professional behavior in international litigation. The article’s powerful plea for regulating international lawyers (including arbitrators) continues to influence today’s debate.

A likely highlight of his career was his 1993 election as co-editor in chief of the American Journal of International Law, the leading publication in the field. He served with great distinction.

His works and teachings show the marks of a fine comparative law tradition. In the face of strong U.S. unilateralist and even isolationist tendencies, Vagts displays an unwavering belief in the rule of international law, and the notion that no nation can claim to be above it.

My favorite recollection among the many moments that we have spent together remains the visit that he and his wife, Dorothy, paid to my native Holland in connection with the formal defense of my doctoral thesis in June 1994. He thoroughly enjoyed the pomp and circumstance associated with doctoral ceremonies at Leiden University–especially the nightly festivities at my fraternity. In the thank-you note that I received from him afterward, he commented that he had not experienced such excitement since V-J Day in 1945!

While he certainly is “part of the pantheon of godlike leading citizens who define the Harvard Law School,” as former Dean Clark once described Vagts’ late international law colleague Abram Chayes, he is anything but an ivory-tower person. He is revered, especially by the foreign students enrolled in the LL.M. program, for being a warm and modest person.

Like so many of his students over the years, I experienced his kindness many times. When I was still single and working for a Wall Street law firm, he contacted me one day and invited me to spend the Thanksgiving holiday with his family at his lovely house in Cambridge. In the past 14 years, I have made it a habit of looking him up, either at his Hauser Hall office or at home, whenever I am in the Boston area. This has resulted in a special friendship that I will cherish forever.

It is to be expected that Detlev Vagts’ retirement will not mark the end of his remarkable career. I am confident that it will not silence his voice–a voice of reason and passionate commitment to the belief that international law and institutions are the greatest hope for peaceful resolution of conflict. It is a voice the world needs to hear, and to heed.