The portrait of Elihu Root in the Harvard Law School Library depicts him as he looked in 1903, when he was 58 and secretary of war under President Theodore Roosevelt. Root wears a thick tie and full vest and morning coat. He is standing, with rimless glasses in his right hand and his left hand in a pants pocket. With graying brown hair parted in the middle, somber brown eyes, and a thick moustache, he is the embodiment of the lawyer-statesman—the idealized lawyer who is a skilled legal technician but, more to the point, a person of practical wisdom and exemplary character. The portrait hangs at the library’s south end, outside a room named for him.

Even a frequent visitor to the Root Room should be forgiven for thinking he was another distinguished graduate of the law school recognized for his accomplishments. The library assumes his eminence, without explaining who he was. He was from an old American family. “My maternal grandfather, with whom I passed much time as a child,” Root wrote in a letter to a historian, “was the son of the man who commanded the Americans in the fight at Concord bridge on the nineteenth of April in 1775.” He was certainly accomplished.

In 1913, when he was a United States senator from New York, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, for advocating that major conflicts between countries be settled by arbitration instead of war. After his chapter at the War Department and before being elected to the Senate, he was Roosevelt’s secretary of state. In that job, he negotiated bilateral treaties with 24 countries, which each committed to using arbitration to resolve disputes. That led to the creation of a world court, officially the Permanent Court of International Justice, which existed until 1946. Root was a kind of godfather to the group of men responsible for the Kellogg-Briand Pact (1928), which failed to end all wars, as it was supposed to, but, by changing the rules of war, all but ended wars of conquest—the lion’s share of wars until then.

The Root quotation on the wall of the room begins, “He is a poor-spirited fellow who conceives that he has no duty but to his clients and sets before himself no object but personal success.” Lawyers more often quote another piece of wisdom from Root found in his authorized biography: “About half the practice of a decent lawyer consists in telling would-be clients that they are damned fools and should stop.”

“About half the practice of a decent lawyer consists in telling would-be clients that they are damned fools and should stop.”

Elihu Root

Still, Root didn’t attend Harvard College or Harvard Law School. He graduated from New York University School of Law, in 1867. The opening of the room in 1939 was the result of a gift to Harvard from Henry L. Stimson, who attended Harvard Law School for two years before becoming Root’s protégé and then partner at his law firm in New York City. (In those days, membership in the New York Bar did not require a law degree and six out of every 10 candidates who took the bar exam had never been to college, let alone law school.

Stimson, like Root, was prominent in government as well as law practice. He was secretary of state for President Herbert Hoover and secretary of war for President William H. Taft and then, a generation later, for President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The year he turned 50, he enlisted during the First World War. He served as an artillery officer in France and left the Army as a colonel in the 31st Field Artillery. Stimson had intended that the gift help endow a professorship in his mentor’s name, but, a dozen years later, after Harvard was unable to raise sufficient additional money, he said he “must leave the use of the fund to the authorities of the university.” Harvard used it for the “equipment and decoration” of an informal reading room in Langdell.

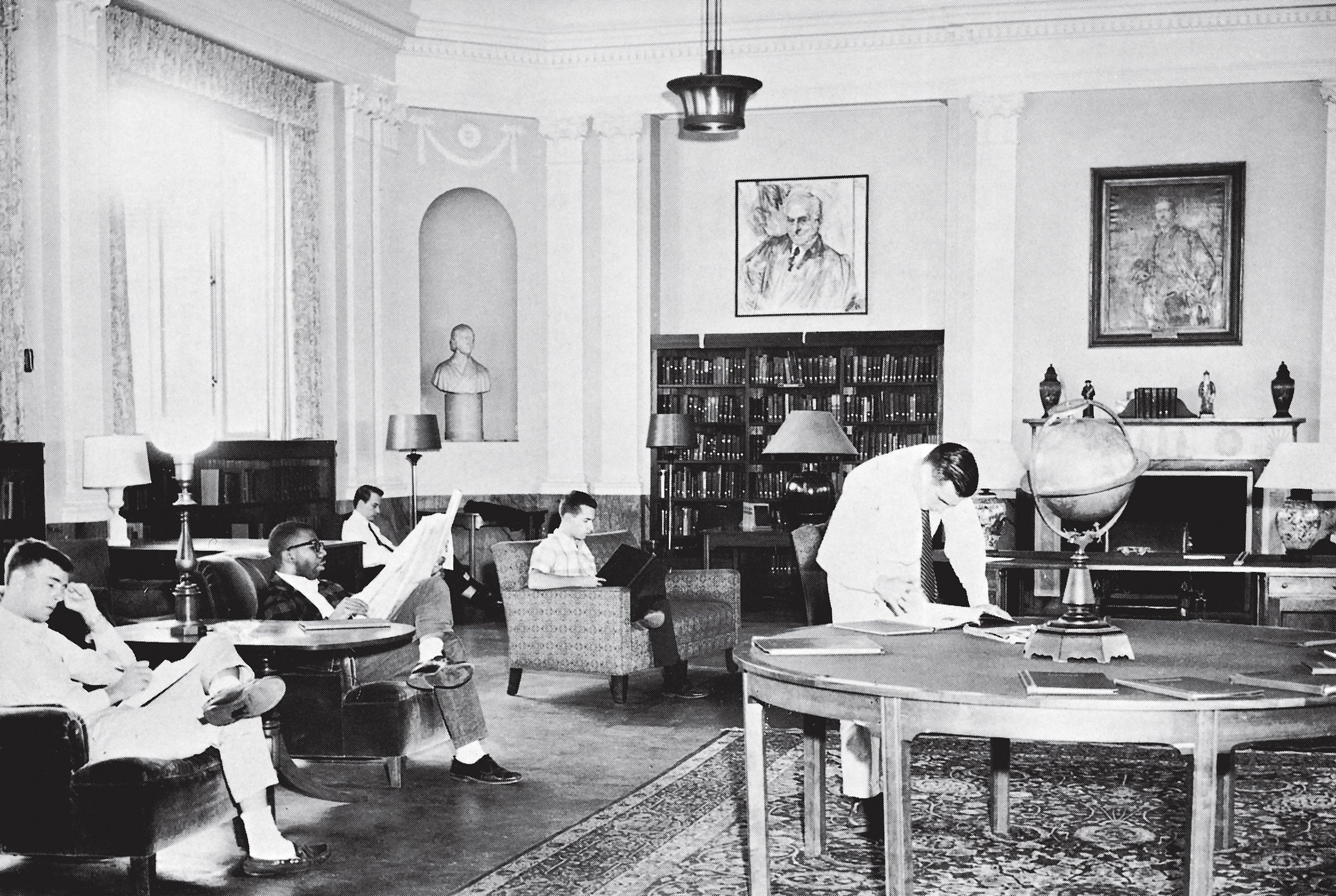

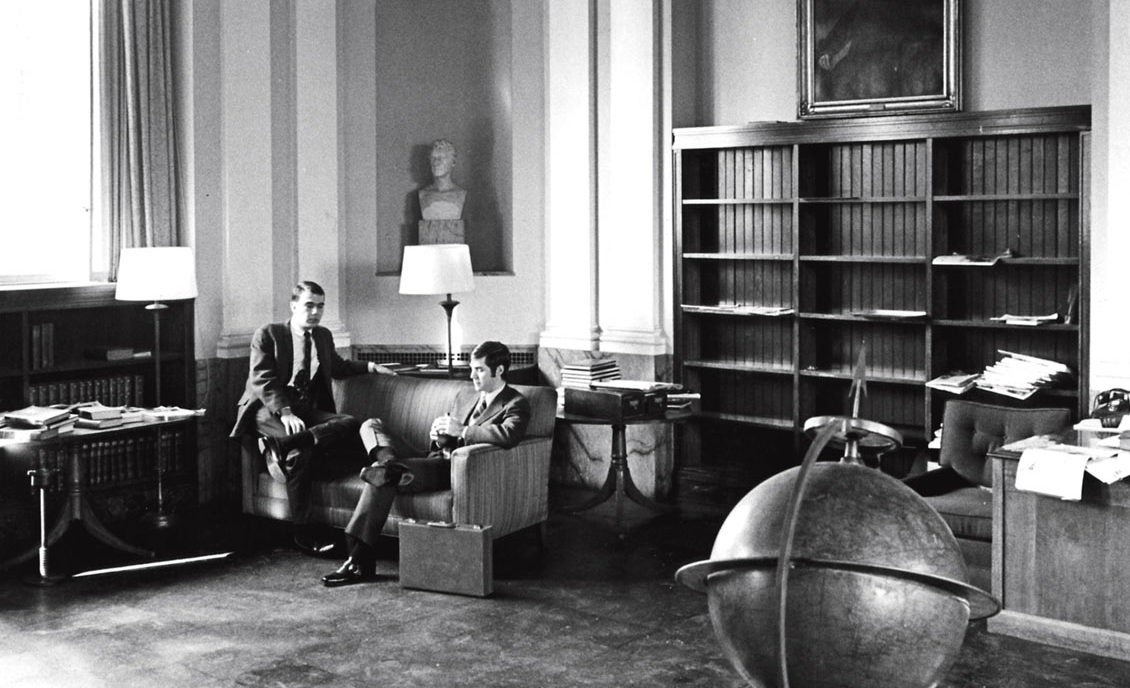

The Root Room was meant to have the feel of a living room—but a stately one, decorated in a neoclassical style. Large and open, with a high ceiling, it was painted an airy blue and white, with ornamental columns emphasizing its height. Paintings and sculptures of distinguished figures from American and British law defined the walls and corners. On the wall opposite the entrance, there was a fireplace with a reproduction of the mantel that, until 1857, stood behind the speaker’s desk in the House of Representatives, in Washington, D.C. Looking back from the fireplace, you could see a gilded clock above the entrance with Roman numerals marking the hours.

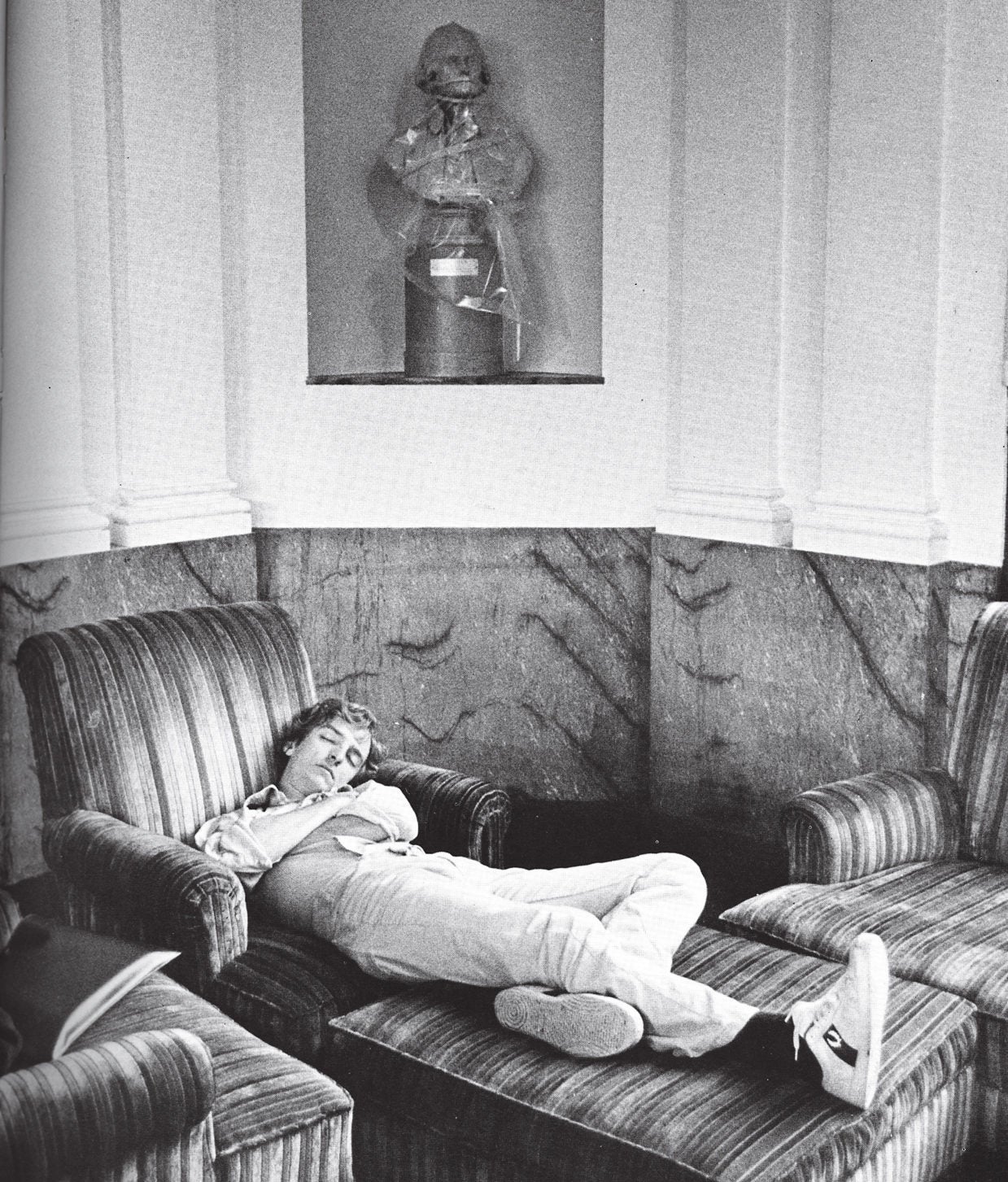

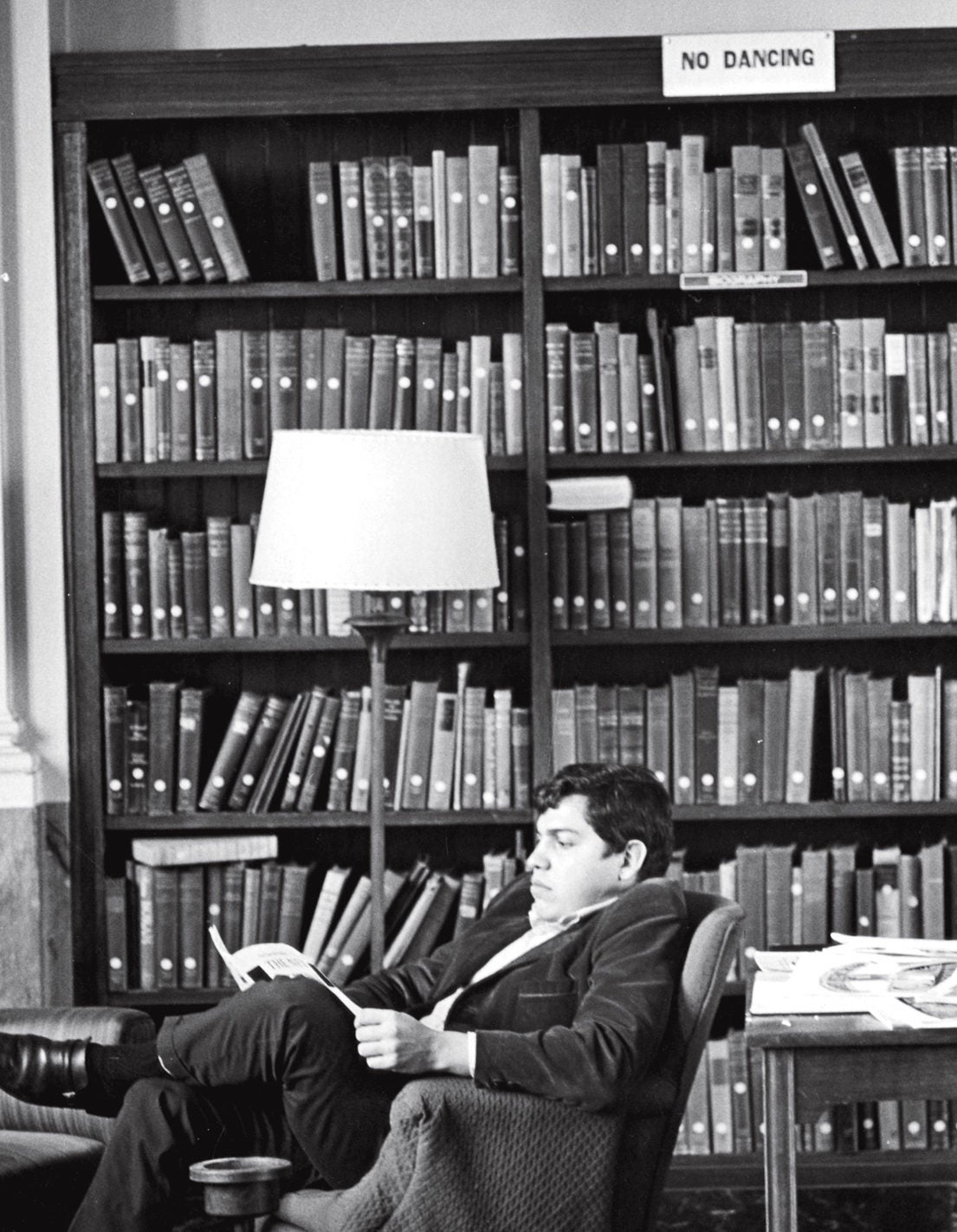

While the room offered newspapers and magazines, primarily it provided students with books—some novels but mostly nonfiction—about the intersection of law and life rather than the law. The furniture included easy chairs where students sprawled, slept, and otherwise made themselves at home, sometimes getting lost in their reading, which transported them across time and space.

“The Trial of Dr. Adams,” Sybille Bedford’s true-crime account, had that power. It’s about an epic 1957 murder trial at London’s Old Bailey of a 58-year-old English country doctor named John Bodkin Adams. Astonishingly, he was acquitted of poisoning an elderly female patient with large quantities of heroin and morphine, though he had irrefutably prescribed them. He was later stripped of his medical license, but he lived into his mid-80s and died a wealthy man, having been the beneficiary of the wills of 132 patients, out of 163 who died in suspicious circumstances.

Bedford wrote this about the trial’s opening, when the clerk of the court addressed the defendant and the defendant addressed the judge:

“Do you plead Guilty or Not Guilty?”

There is the kind of pause that comes before a clock strikes, a nearly audible gathering of momentum, then, looking at the Judge who has not moved his eyes:

“I am not guilty, my Lord.”

It did not come out loudly but it was heard, and it came out with a certain firmness and a certain dignity, and also possibly with a certain stubbornness, and it was said in a private, faintly non-conformist voice. It was also said in the greatest number of words anyone could manage to put into a plea of Not Guilty.

Much of the Root collection was biography, with many books about icons of American law, like John Marshall, Daniel Webster, and Abraham Lincoln, and others about obscure figures, like Charles Henry Fernald, a county judge in Santa Barbara, California, and George Shiras, a Supreme Court justice from 1892 to 1903. Some of it was macabre (e.g., “The Reluctant Hangman: The Story of James Berry, Executioner – 1884-1892” by Justin Atholl and “Wills of the U.S. Presidents” by Herbert R. Collins and David B. Weaver). Some of it was esoteric (“Forbrydertyper hos Shakespeare” by August Goll—“Criminal types in Shakespeare,” an authorized translation from Danish). HLS librarians regarded the books as entertainment and, compared with legal textbooks, they were. But many in the collection seriously addressed subjects that the law school’s curriculum barely considered. The books were Harvard Law School’s version of what Harvard Business School gathered in its Power and Morality Collection. The law school’s goal was to teach students to think like lawyers, not how to practice law or even what lawyers did in practice. The Root Room provided books about both for a form of independent study in a counter-curriculum.

Brown v. Board of Education is often called the most important Supreme Court ruling in the 20th century. It was not yet two decades old when I arrived as a 1L in 1973 and became a Root Room regular. Many people know that Thurgood Marshall was the lawyer who argued in favor of what the Court unanimously decided in 1954—that segregated public schools violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution. Because of what Marshall stood for as a champion of equal rights, President Lyndon B. Johnson picked him to be solicitor general—the first African-American to serve in that role—and, then, to sit for 24 years on the Supreme Court.

A biography of Davis, which was part of the Root Room collection, raised one of the most difficult ideas in American justice: “the principle of non-accountability.”

Yet even in the legal world, relatively few know that the lawyer who argued in favor of the status quo in that case, and, therefore, for letting states maintain separate public schools for black students, was John W. Davis. In 1953, Davis’ daughter was seated next to Marshall’s wife in the visitors’ gallery of the Court when it heard oral argument in the Brown case. The daughter congratulated the wife after Marshall finished his argument. Mrs. Marshall replied about Davis, “My husband admires him so much.” Marshall himself later said, “He was a great advocate, the greatest.”

How could the lawyer who led the country’s most important legal campaign for racial justice venerate his adversary bent on thwarting it?

In 1973, the Root Room acquired a book that answered the question. “Lawyer’s Lawyer: The Life of John W. Davis” by William H. Harbaugh, who was a professor of history at the University of Virginia, was, in the words of The New York Times Book Review, “a monument of scholarship and readability.” It was my introduction to the counter-curriculum. Davis argued more cases (140) before the Supreme Court in the 20th century than any other lawyer, until he was surpassed by a deputy solicitor general who worked for almost 35 years in the SG’s office. In the 1930s, Marshall said, he often skipped classes at Howard University School of Law, in Washington, D.C., to hear Davis argue before the Court.

Davis was the ultimate craftsman, the book explained, a genius at arguing in appellate courts, especially America’s highest. Other famous lawyers were in awe of what Harbaugh called “his capacity for total absorption,” his ability in a case “to master the record within a few hours.” (A lawyer who worked with him said, “He could recite you a page of Dickens without even thinking about it.”) Then, in “euphonious language” and an “authoritative baritone voice,” he had the facility “to simplify complex matters with a few pithy Anglo-Saxon phrases devoid of adjective and drained of all emotion.”

That helped make Davis “the greatest Solicitor General in history,” Harbaugh wrote, when he held the job for five years under President Woodrow Wilson, though other contenders for the title came after him. He was a successful American ambassador to Great Britain after he resigned as solicitor general and ran for president as a conservative Democrat, losing to the Republican Calvin Coolidge in 1924, but it was as a lawyer that he defined himself for history. Among elite lawyers, he was one of the most admired in the profession, with his name put at the front of the name of the Manhattan law firm he joined in 1921, when he was 48. Two generations after his death, the firm of Davis, Polk & Wardwell remains among the most respected corporate law firms in the world.

Henry Stimson’s gift established the Root Room, where students could explore broadly.

Richard Kluger wrote the Times review that lauded Harbaugh’s book, but he judged Davis as Harbaugh did not. Kluger asserted: “That he is scarcely remembered outside of his profession (though still idolized within it as the model of the appellate lawyer) is not merely comment on our short memory of public figures who decline to turn cartwheels in quest of our acclaim. It is, as well, testament that the values for which John Davis stood unbending throughout his 81 years—the sanctity of property, the immutability of laws, the obligation of the individual to sink or swim on his own—have been challenged by other principles in our ongoing national ferment over the definition of a just society.”

In 1975, in “Simple Justice,” his landmark history of the Brown case, Kluger repeated that thought and much of that language in his account of Davis’ background as a Southerner. But he added to that paragraph about the meaning of a just society: “Part of that ultimate definition, it became clear in the aftermath of the Second World War, would hinge on settling the status of black Americans. John Davis’s role in that settlement was determined by one of the few shortcomings in his otherwise sterling character: all his life he was a gentleman racist.” As Harbaugh put it, “his heart was really with the white social order.”

Was it fair of Kluger to condemn Davis as a racist, and not let his appraisal of the man rest on the quality of his advocacy? As Harbaugh explained, and Kluger quoted, Davis adhered “absolutely to the principle that the lawyer’s duty was to represent his client’s interest to the limit of the law, not to moralize on the social and economic implications of the client’s lawful actions.” In admiring Davis, Thurgood Marshall accepted that tenet, which the legal scholar Murray Schwartz called the “principle of non-accountability” at the heart of the American adversary system.

The system depends on lawyers vigorously representing each of the opposing parties in a dispute. They can do that, the theory goes, only if they are not held responsible for what society in general, and a judge and jury in particular, find repugnant in the actions of clients the lawyers are representing. That is among the most difficult ideas in American justice. It was debated in the 1970s when the American Civil Liberties Union, then headed by Harvard Law School graduate Norman Dorsen, defended the right of the National Socialist (Nazi) Party of America to march in uniforms with swastikas on armbands through Skokie, Illinois, then a village of 70,000 people with 5,000 Holocaust survivors.

It is being debated again today, within the ACLU, too. Some staff members have questioned whether the principle of non-accountability still applies when what’s at stake is hate speech in this era of polarized politics and extremism swollen around the globe by social media. They have protested the organization’s defense of Milo Yiannopoulos, the “alt-right” provocateur who, the ACLU recognizes, “has fostered both anti-Muslim bias and disdain for women in one breath, characterizing abortion as ‘so clearly bad for women’s health that it falls second only to Islam.’”

A frolic and detour in the Root Room led to that fundamental issue. Similar excursions led to others as important.

In 1990, after a half century, the library moved most of the books out of the Root Room and remade it into a center of scholarship where researchers can work with materials brought in from the school’s Historical & Special Collections—as the library describes, “nearly three thousand linear feet of manuscripts, over three hundred thousand rare books, and more than seventy thousand visual images.” The décor is the same, but the furniture has been thinned out. The room feels even airier and looks beautiful. It’s still the Root Room, but it’s really RR 2.0. “The Library remains the largest academic law library in the world, and continues to reinvent itself to meet the needs of the law school,” the school’s website says.

The library had contemplated the change for several years, but, as a librarian told me, it was “the asbestos contamination in the Treasure Room, in the spring of 1990, that ultimately accelerated the relocation plan.” The Caspersen Room, as it’s now called, is at the north end of the library and serves as a space for exhibitions, such as the 2005 “Retrospective Honoring Charles Hamilton Houston on the Grand Opening of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice” at the law school. An HLS graduate, Houston was dean of Howard Law School and litigation director of the NAACP, the great lawyer who was the main architect of the strategy that Thurgood Marshall and others carried out.

What the law school of earlier decades left to the old Root Room to teach about the life of the law is now part of the school’s curriculum.

Around the time of the change, the legal profession emerged as a subject of first-rate scholarship among law professors including HLS’s David Wilkins ’80, who is now director of the school’s Center on the Legal Profession and vice dean for global initiatives on the legal profession. What the law school of earlier decades left to the old Root Room to teach about the life of the law is now part of the school’s curriculum. That’s so in courses like Challenges of a General Counsel, which Wilkins co-teaches with Ben Heineman, the former senior vice president and general counsel of GE, and Cross Border M&A: Drafting, Negotiation & the Auction Process, which Mitchell Presser, the head of the U.S. M&A practice of the global law firm of Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, teaches, and in the many legal clinics, student practice organizations, and externships that have transformed what students learn and how.

Law professors got interested in the legal profession because, as major law firms began to morph into economic powerhouses, many leading American lawyers were concerned that the elite segment of the profession was abandoning “principle for profit, professionalism for commercialism,” as a report of the American Bar Association put it. Davis, Root and Stimson had all been accused of doing the same thing. As Louis D. Brandeis LL.B. 1887 described the problem around the time Root was in the Roosevelt administration, elite lawyers had let themselves “become adjuncts of great corporations” and had “neglected the obligation to use their powers for the protection of the people.” A generation ago, Wilkins and others began a challenging quest that continues today: to persuade elite lawyers to give the ethical dimensions of lawyering much more attention.

I graduated from HLS without really understanding what the word “professional” meant in defining the legal profession and how that affected the behavior of lawyers in the most influential corporate law firms. For that matter, I didn’t know what the solicitor general actually did in the U.S. Justice Department or understand many other aspects of law and the legal culture that struck me as significant because of what I read in the Root Room.

“Simple Justice” was one of the last books I read in the room before graduating in 1976—especially memorable, it later dawned on me, because the book’s revelations about what happened at a profound intersection of life and law in the United States fortified my interest in a career as a journalist and an author of books about legal affairs. In “Skadden: Power, Money, and the Rise of a Legal Empire,” “The Tenth Justice: The Solicitor General and the Rule of Law,” and other books, I have written about answers I have found and stories that helped explain the answers.

I focused on the Skadden firm, rather than Davis Polk or another of the old New York-based firms, because it symbolized the transformation of the large law firm after World War II. It opened on April Fools’ Day in 1948, a tiny operation with no clients; three partners who had been passed over for partnership at well-established firms; and one associate, Joe Flom, from HLS’s two-year, postwar Class of 1948. Thanks to its willingness to serve as special counsel for special purposes—matters too dicey for some other firms to take on—it grew to 75 lawyers in 1975. By 1990, on the basis of its lucrative practice in counseling companies involved in fighting off or doing corporate takeovers, it was a mega-firm with 1,000 lawyers. Flom exhorted his colleagues, “We’ve got to show the bastards that you don’t have to be born into it.”

At a celebration of Skadden’s 40th anniversary in 1988, when it was making more money than any law firm ever had and was the colossus of the legal profession, Flom issued a warning. He instructed: “We must remember that the history of major institutions is that they are not permanent. The only permanence comes from what you make of it, or what the institution makes of itself. If it becomes a dinosaur, it will disappear.” It was his version of the lesson that the law school demonstrated it understood when it overhauled its curriculum, and that the library showed it grasped when it remade the Root Room.