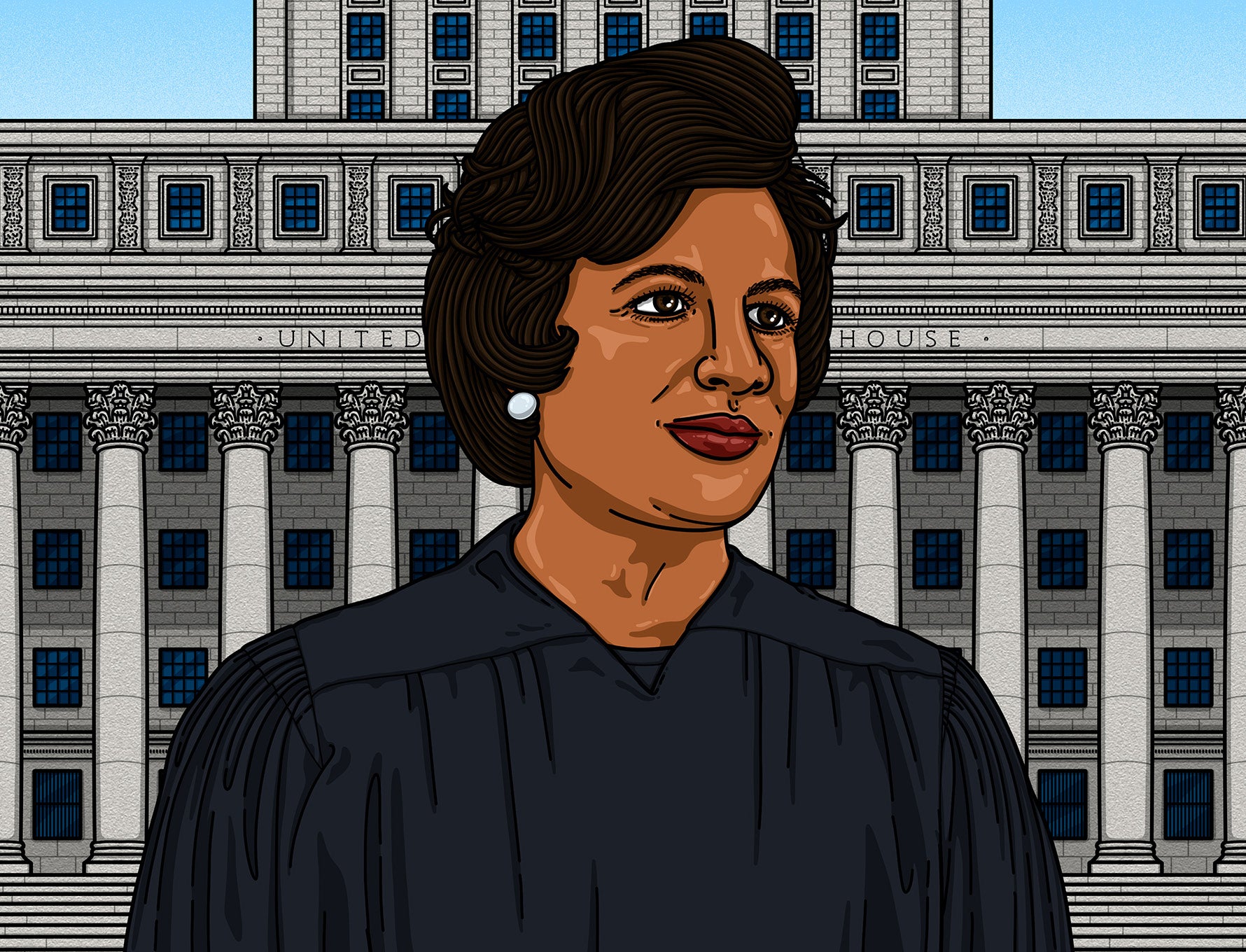

When she was a small child, Tomiko Brown-Nagin learned about Thurgood Marshall, who as a Supreme Court justice was featured in encyclopedias she read. It wasn’t until college that she learned about Constance Baker Motley, and only in a cursory way. Yet Motley, like Marshall, also played an integral role on the Brown v. Board of Education case and with the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, and was the first Black woman to serve as a federal judge, among her many other singular achievements.

Decades later, the story of Motley is still little known. And Brown-Nagin, the Daniel P.S. Paul Professor of Constitutional Law at Harvard Law School, who serves as dean of Harvard Radcliffe Institute, wanted to do something about that. Her previous book, “Courage to Dissent,” on the history of the civil rights struggle in Atlanta, included a chapter on Motley’s work as lead counsel on an Atlanta school desegregation case. Shocked by how little attention Motley had received, Brown-Nagin started researching every aspect of Motley’s life, including by interviewing her colleagues and family members. The 10-year process of uncovering the story of a “transformational lawyer, a trailblazing woman, and an exceptional African American” culminated in her new comprehensive biography, “Civil Rights Queen: Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality.”

It is a story of how Motley, “without making much fuss,” grasped opportunities based on her qualifications and talent while facing obstacles and discrimination because of her gender and race. Born in 1921, Motley grew up in New Haven, Connecticut, the child of West Indian immigrants who taught her “to think of herself as special.” She had no opportunity to pay for higher education until a benefactor who heard her give an impassioned speech offered to pay for college and the law school education that she believed would help her make her mark on society.

Indeed it did, as, after graduating from Columbia Law School, Motley joined the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund and was the only woman whose name appeared on the Brown case briefs. She also argued groundbreaking civil rights cases such as the fight to desegregate the University of Mississippi and on behalf of the Children’s Crusade protesting segregation in Birmingham. Motley won nine of 10 cases before the Supreme Court that “remade American law and society.” Yet she was still paid less than men at the organization and was passed over to lead it when Marshall left to become a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals, a decision she blamed on gender discrimination.

Motley later became the first Black woman elected to the New York State Senate and the first appointed as a federal judge, to the U.S. District Court in New York City by President Johnson in 1966. Yet she was never nominated to the U.S. Court of Appeals because of opposition to her, which “illustrated the enduring paradox of her career,” Brown-Nagin writes. “After her record of extraordinary achievement, she hit a roadblock that illustrates the broader dynamic of exclusion amid access in her life, and the ongoing challenges faced by outsiders.”

Brown-Nagin highlights that paradox in Motley’s judicial career. Despite the expectations by many in the legal world that she would be biased on behalf of defendants, Motley’s decisions were careful and even-handed, the author contends, with only a handful of her more than 2,500 judicial cases pushing the law in favor of the disadvantaged. At the same time, she was critiqued by some outsiders for being part of the power structure.

“She was able to achieve quite a lot in every inside position that she occupied,” Brown-Nagin said in an interview this past spring. “And if one tries to keep score, I think that she turns out looking much better than some of these agitators who are critiquing her for daring to be a part of the system.”

“I hope that Motley would teach that one can both be successful and demonstrate great humanity, and I would be very pleased if people who read the book can take away that lesson.”

—Tomiko Brown-Nagin

While Motley, who died in 2005, never upended the system as a judge, she nevertheless effected profound change, including increasing access to higher education for African Americans as a civil rights lawyer as well as paving the way for other women and people of color on the bench, including Ketanji Brown Jackson ’96, who has just become the first Black woman on the Supreme Court. For Brown-Nagin, the confirmation hearings for Jackson recalled Motley’s contentious confirmation hearing more than 50 years ago; both of them included critiques of the nominees’ practice backgrounds.

“As a lawyer and historian deeply familiar with this professional realm, and with the history of race and gender in America, I would have predicted that despite her achievements, Judge Jackson would have encountered some pushback,” she said. “But I would not have predicted the extent of the pushback and the extent of continuity between her experience and Judge Motley’s experience.”

If Motley had gotten the chance to serve on the Supreme Court, Brown-Nagin believes she would not have been deeply ideological but would have contributed her expertise on issues of inequality. As a person who believed in decorum and civility, she also would have brought great honor to the Court, she added.

Brown-Nagin hopes that current and future generations will learn Motley’s story, which showcases her resilience and the many different ways one can make contributions over the course of a career, she said. And her great dignity and commitment to leading an ethical life should be a model for others.

“I hope that Motley would teach that one can both be successful and demonstrate great humanity,” said Brown-Nagin, “and I would be very pleased if people who read the book can take away that lesson.”