Last December, protests in Sudan, caused in part by deteriorating economic conditions, sparked a revolution that led, ultimately, to the ouster of President Omar Hassan al-Bashir, a constitutional declaration signed by military leaders and the main opposition coalition, and the formation of a new transitional government. During this tumultuous year, watching from Washington, D.C., Nasredeen Abdulbari LL.M. ’08 continued to do what he has been doing since he was a student at Harvard Law School. As a member of the Fur tribe from Darfur, and as a journalist, researcher, and former professor of international law at the University of Khartoum, he analyzed the threats to peace and stability in Sudan, wrote eloquently about his country’s history of ethnic, religious and regional conflicts, and above all, identified paths toward resolution.

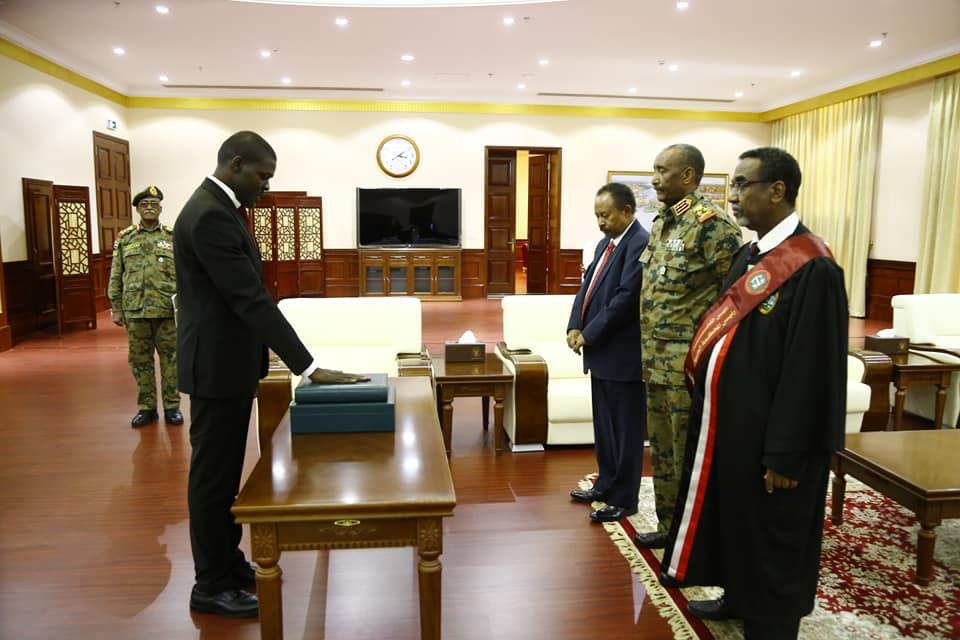

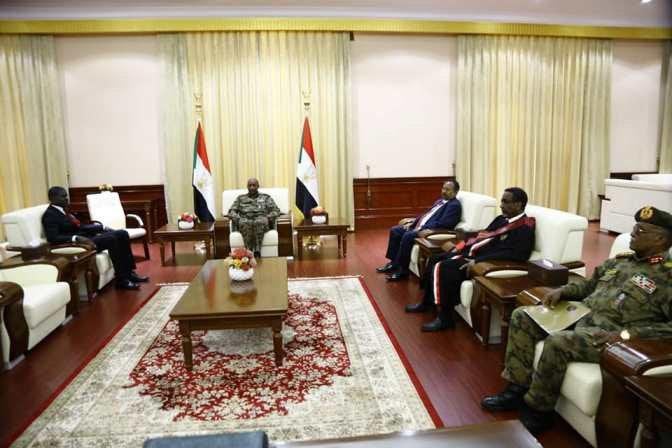

“History,” he notes, “is full of surprises,” and for Abdulbari, the significant role he has now undertaken is one of them. In September, after a rigorous vetting process, he was sworn in as Minister of Justice in the cabinet of Sudan’s new Prime Minister, Abdalla Hamdok.

Even before he enrolled at HLS, Abdulbari planned to pursue a career in law teaching, but did not expect to serve in government, at least not this soon. “I thought I would work someday in an advisory position, or maybe run for office at some point in the future, in a democratic Sudan,” he notes. “We were always struggling, trying to improve the conditions of my country, but I never thought this would actually happen in 2019.”

At HLS, he studied American immigration law and policy, international law, constitutional law (“that was my favorite course, actually”), and international human rights law. He also observed the American political process during Barack Obama ’91’s first presidential campaign.

“I learned a lot from my life in the United States, as well as from my professors and classes,” Abdulbari recalls. “I learned the arguments for and against the theory of originalism or intentionalism, the arguments for federalism in the U.S. and in general, and how the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, and specifically the Equal Protection Clause, was crucial to the civil rights movement in America. And as a person who was engaged in teaching before joining Harvard, I also learned new teaching skills and methodologies from the way my professors taught.”

After graduation, Abdulbari returned home, resuming his teaching work at the University of Khartoum and undertaking a Satter Human Rights Fellowship from HLS to work with the Sudan Social Development Office (SUDO), a human rights and development NGO. Nine months later, SUDO was one of many international and Sudanese organizations shut down during a government crackdown triggered by al-Bashir’s fury over an International Criminal Court indictment. “We were accused of providing information to the ICC, which was absolutely not true,” he explains. Like most of his colleagues who were working for those organizations, Abdulbari felt unsafe in Sudan. Fortunately, he was able to move to Kenya, where he worked as a researcher and consultant, and then to return to the United States, where he lived until the day of his appointment.

On September 24, barely three weeks after he was sworn in as Minister of Justice, Abdulbari represented the Sudanese government at a meeting of the U.N. Human Rights Council in Geneva. His speech before the Council traced the events that led to the formation of Sudan’s transitional government, and outlined the steps that his country will take going forward.

One of these initiatives is to open offices throughout Sudan for the U.N. High Commissioner on Human Rights. “Our approach is that as a new government, we should have nothing to hide as far as human rights are concerned,” he explains. “We need to know the wrongs so we can address them.” Sudan also plans to accede to all the international human rights conventions to which it is not yet a party — including the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women and the Convention against Torture, among others.

In addition, “we want to address other deficiencies in our laws — laws that do not serve justice, that do not provide protection for individuals or groups, or that were enacted to serve the best interests of the [Bashir] regime, or people who were connected to it,” Abdulbari adds. “Lawyers and civil society activists [in Sudan] have been working on law reform for decades. These groups have proposals to give us, so we will rely on them.” Individuals from organizations outside of Sudan, from the American Bar Association to the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights, have also offered their assistance and expertise.

The new government’s ambitious agenda also includes a comprehensive peace process to address the ongoing conflicts in Darfur and other regions. “We believe peace can only be achieved if we address the root causes of Sudan’s wars, which are the marginalization by the state of the peripheries,” Abdulbari reported in Geneva.

“I think this transitional period is foundational for establishing a modern state in Sudan,” he observes. “In 1956, all people wanted was to gain their independence. Sudan was not founded on principles, and that is why we have been in wars and instability for more than five decades. This revolution has offered the people of Sudan a historic opportunity to establish a state based on freedom, justice, human rights and democracy. This is what will allow Sudan to live in peace and to move forward.”

Nasredeen Abdulbari: ‘Lawyers are the cement of society.’

As he prepared to graduate from Harvard Law School in June of 2008, Nasredeen Abdulbari was profiled in the Harvard Gazette. He discussed his vision of what a more fully developed constitutional system could do for his home country of Sudan and his intent to devote himself to human rights and constitutional law.