When the Taliban crashed through the gates of Kabul, where Saeeq Shajjan LL.M. ’10 was practicing law, everything changed for the country and for him.

“It is such a painful time for almost every Afghan,” said Shajjan. “We lost a country that we love. Honestly, there is nothing for us left in that country.” No one is safe in Afghanistan anymore, he said, but particularly those like him with professional and academic backgrounds who worked with the international community and the United States.

“It is such a painful time for almost every Afghan. We lost a country that we love.”

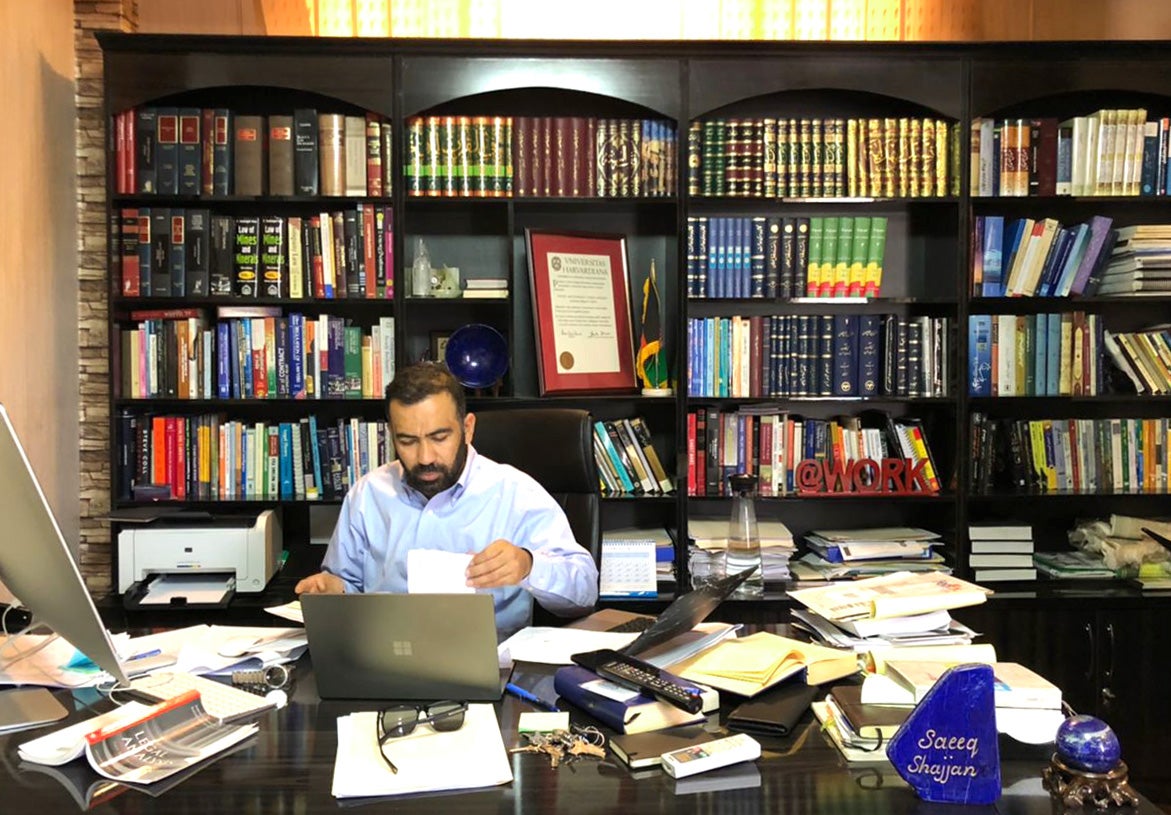

Speaking from a hotel room in Toronto, where he was quarantined because of COVID, Shajjan recounted how he fled, leaving behind most everything dear to him but for his family and the few clothes he could carry: his legal practice; the house he built, including his beloved library; his colleagues from his law firm; and the country he was devoted to and tried to improve every day. Yet he feels lucky, he says, at the same time as he is experiencing survivor’s guilt. After the Talban’s takeover of Afghanistan, he was able to get out while so many others could not.

He could have left a lot earlier. Friends and family had tried to convince him to stay in the United States after he graduated from Harvard Law. But he wanted to go back to contribute to the development of his home country, particularly to build its legal capacity. He started his own firm and employed more than 20 people. He sponsored programs for law students and private law schools. Despite being threatened by extremist elements, he was still determined to stay.

As people around the globe watched in horror as images of chaos at the Kabul airport flashed across their screens, Shajjan was living through it. Friends from the United States helped arrange seats on a flight for him and his family to Doha, Qatar, on August 17, two days after the Taliban took over Kabul. Rumors were spreading that people were able to get on planes to leave the country even without proper documentation, which led to jammed roads to the airport. He drove there in a convoy with his wife, three children, two sisters, and his parents, eventually making their way through three checkpoints. But as they neared the entrance of the airport, they were turned away by Taliban guards who threatened to beat Shajjan when he got out of his car to plead his family’s case. When he tried again later, other stone-faced Taliban guards simply refused to listen to him. Finally, as his desperation grew, he found someone from the Qatar embassy, who said Shajjan’s name was on a list, and urged him to return with his family. By then, it was difficult to traverse the crowd. But he found an ally in another member of the Taliban, whom he managed to convince to shepherd them to the airport.

Shajjan and his family eventually made it to Toronto as part of a Canadian resettlement program.

The scenes that greeted them were shocking. People were stampeded, and the Taliban shot in the air to ward off onrushing crowds, wounding some bystanders. Shajjan’s 9-year-old daughter saw a man bleeding from a bullet wound to his thigh and pointed him out to his father. He told her they couldn’t do anything for him and had to leave. They got on the plane to Doha, where Shaijan applied to be part of a Canadian resettlement program for Afghans, for which he was eligible since he had done work for the Canadian government. On September 2, he and his family traveled to Canada. He doesn’t yet know where they will live, but he expects that he and his family to stay in the Toronto area where he has contacts in the legal community. Although he is not qualified to practice law in Canada, he is willing to take the necessary classes and exams. In the meantime, he will do whatever he can to support his family as they prepare to start their new life.

He is also trying to help people who remain in Afghanistan, including most of his employees. Many of them are in hiding from the Taliban, he says, staying in different houses with relatives and friends each night. Like him, they are also eligible to emigrate to Canada, according to Shajjan, and he is calling and emailing everyone he knows who might be able to help them escape.

He is trying to help people who remain in Afghanistan, including his employees.

Conditions in Afghanistan are dire, he says. He spoke to judges who showed up for work and were told that they are no longer needed. The banks are short of money, and most businesses and government offices are closed. Companies are not paying their employees. And the U.N.’s World Food Programme has warned that severe food shortages are looming.

“Very well-educated people, they’re on the streets right now. They’re begging,” Shajjan said. “So that is the most difficult thing that you would want to see and hear about Afghanistan, that people do not have money. The prices of almost everything in the city they’re hiking on a daily basis. And I’m afraid it will have very difficult consequences to the people of Afghanistan.”

“Very well-educated people, they’re on the streets right now. They’re begging.”

To a large extent, the Afghan government and politicians are responsible for what happened to the country, Shajjan says, pointing to widespread corruption that impeded people’s trust in their leaders. Despite billions of dollars in international funding, he said, “We were not able to build a rule of law system that people would be able to defend themselves if a difficult time comes.” He also criticizes the Biden administration for its decision to withdraw all U.S. troops, contending that maintaining a small force until the end of the year could have brought stability during negotiations that were taking place between the Afghan government and the Taliban.

To help ameliorate the situation, Shajjan would like to see the international community apply pressure on the Taliban and prevent Pakistan from interfering in the country. Yet he is concerned that the world will turn away from the suffering among Afghan citizens and the Taliban will operate with impunity.

“Honestly, I’m really hopeless,” he said. “I do not think that anyone would do much unless they see their own interests to be threatened. Then they might do something against the Taliban. But other than that, to be frank, I do not expect much because what I see from the leaders of Afghanistan as well as outside of Afghanistan, our lives do not matter. And that has been proven time after time.”

Not long ago, he and many other Afghans were hopeful about the future of their country. Even amid the corruption, he saw myriad signs of progress.

Not long ago, he and many other Afghans were hopeful about the future of their country (See this earlier interview with Shajjan). Even amid the corruption and other problems over the past 20 years, he saw myriad signs of progress. There was a peaceful transfer of power from one president to another as well as parliamentary elections. Many more people were going to school at all levels, including girls and young women who previously were barred from education. The media operated without government interference. The economy was improving, and the private sector was creating more jobs.

“I do not expect much because what I see from the leaders of Afghanistan as well as outside of Afghanistan, our lives do not matter.”

So many things have been lost, including, he fears, the kind of education he cherishes. He heard that the minister of higher education appointed by the Taliban told university professors that he values people who went to madrasas over those with any type of university degree. “So that actually is killing that respect that people would have for education,” said Shajjan. “For them, education is only going to madrasas and understanding Islam from their own eyes. With a lot of people like me, they will not accept their interpretation of Sharia law.”

Shajjan says he is a proud Muslim, who believes Islam is not about killing or violence. He is also proud of his education and his achievements in the law. That is something no one can ever take away from him.