It was as a law student that Obama first made history—and national headlines—when he was elected the first black president of the Harvard Law Review in the spring of 1990.

And as a law student, Obama met many professors and classmates who would prove helpful in his meteoric political rise from state senator to president of the United States in five years.

Each seems to have a story about how much Obama stood out.

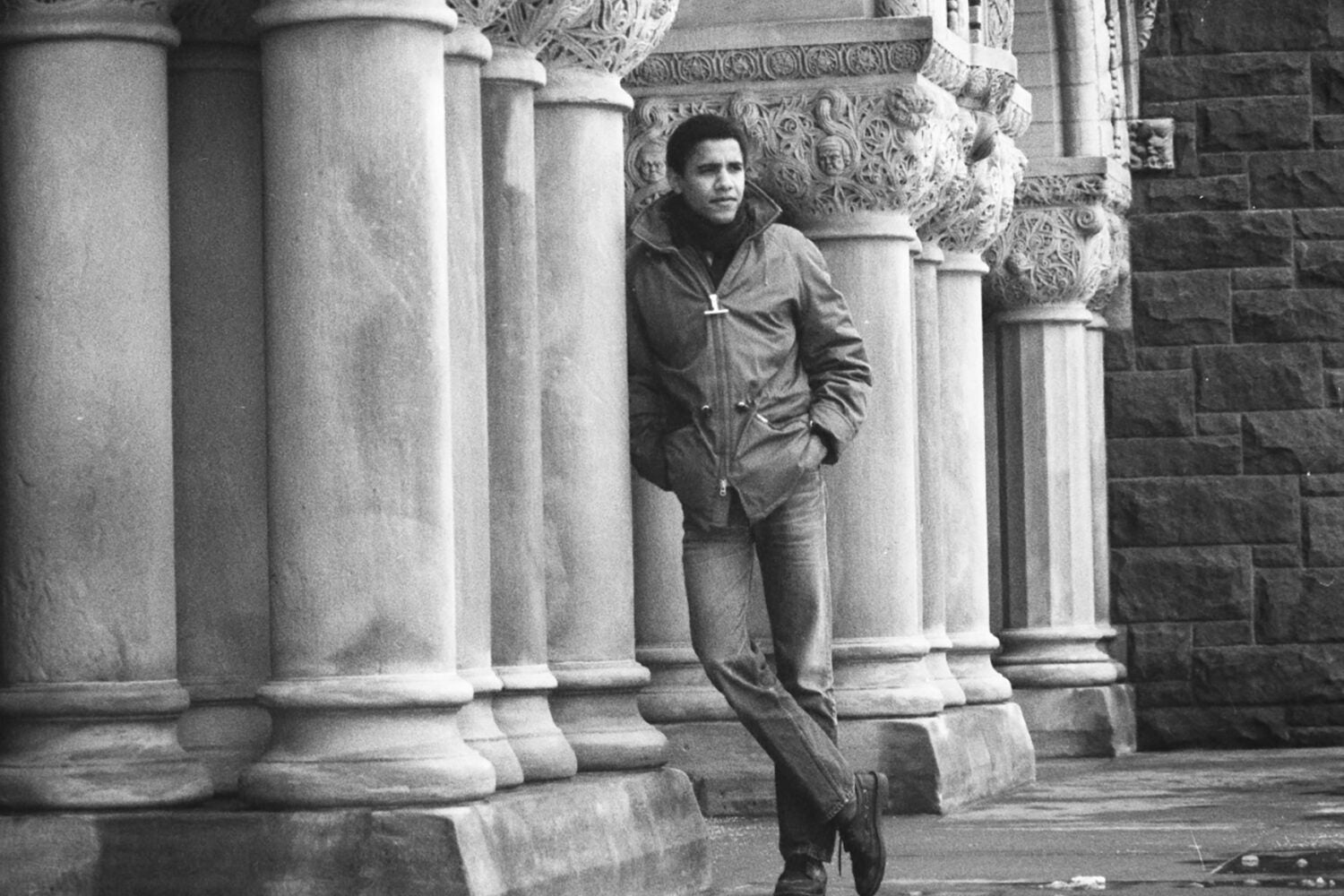

Sure, Obama’s unique, and by now, familiar personal history, set him apart. He arrived on campus at the age of 27 in the fall of 1988, older than many of his classmates after a stint as a community organizer in Chicago. Professor Kenneth Mack ’91, his classmate and friend, says Obama didn’t speak much at first about other aspects of his unique background, including a childhood spent in Hawaii and Indonesia or the fact that his mother was white.

Most remarkable, given his complex identity, was how comfortable Obama seemed with himself. “Barack’s identity, his sense of self was so settled,” recalled Cassandra Butts ’91, who met him in line at the financial aid office, in an interview with PBS’ “Frontline.” “He didn’t strike us in law school as someone who was searching for himself.”

Obama’s performance inside and outside the classroom attracted more notice than his distinctive personal story. In the spring of his first year at law school, Obama stopped by the office of Professor Laurence Tribe ’66 inquiring about becoming a research assistant.

Tribe rarely hired first-year students but recalls being struck by Obama’s unusual combination of intelligence, curiosity and maturity. He was so impressed in fact, that he hired Obama on the spot—and wrote his name and phone number on his calendar that day—March 31, 1989—for posterity.

Obama helped research a complicated article Tribe wrote making connections between physics and constitutional law as well as a book about abortion. The following year, Obama enrolled in Tribe’s constitutional law course.

Tribe likes to say he had taught about 4,000 students before Obama and another 4,000 since, yet none has impressed him more.

Professor Martha Minow recalls: “He had a kind of eloquence and respect from his peers that was really quite remarkable,” Minow says. When he spoke in her class on law and society, “everyone became very attentive and very quiet.”

Artur Davis ‘93 still vividly recalls how much Obama inspired him with a speech he gave during orientation week on striving for excellence and mastery. Davis, now a United States Congressman from Alabama, insists he left that speech by Obama convinced he’d just heard a future Supreme Court justice—or president.

Obama displayed other traits in law school besides eloquence that would define his success as a presidential candidate.

“You could see many of his attributes, approach to politics and ability to bring people together back then,” says Michael Froman ’91, who worked with Obama on the Law Review.

As a campus leader, he successfully navigated the fractious political disputes raging on campus. By 1991, student protestors demanding the school hire more black faculty had staged a sit-in inside the dean’s office and filed a lawsuit alleging discrimination.

Obama spoke at one protest rally, but largely preferred to stay behind the scenes and lead by example, recalls one of the protest leaders, Keith Boykin ‘92. Obama opted against taking sides in the ideological disputes that often divided the politically polarized Law Review staff, casting himself instead as a mediator and conciliator. That approach earned the enduring respect of Law Review members including those not necessarily inclined to agree with his political views today.

“He tended not to enter these debates and disputes but rather bring people together and forge compromises,” says Bradford Berenson ’91, who was among the relatively small number of conservatives on the Law Review staff.