Discovery of Poster Rekindles Mystery of Lost Student

On a Saturday afternoon in November 1937, 1L Frederick William Burgess left his Perkins Hall dorm room to attend a Harvard football game. Twelve hours later, his discarded gray hat, watch, and neatly folded overcoat appeared on the Longfellow Bridge over the Charles River.

Sometime in between, Burgess vanished.

William Burgess, a 21-year-old Cincinnati native, soon became the target of a nearly three-month nationwide search ordered by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and the subject of sightings as far away as West Virginia.

Yet Burgess’ disappearance was long forgotten on campus until last June, when Harvard Law librarian Steven Smith logged onto eBay, the Internet auction site. There, Smith bid for a 1938 flyer offering a $500 reward for information about the missing student.

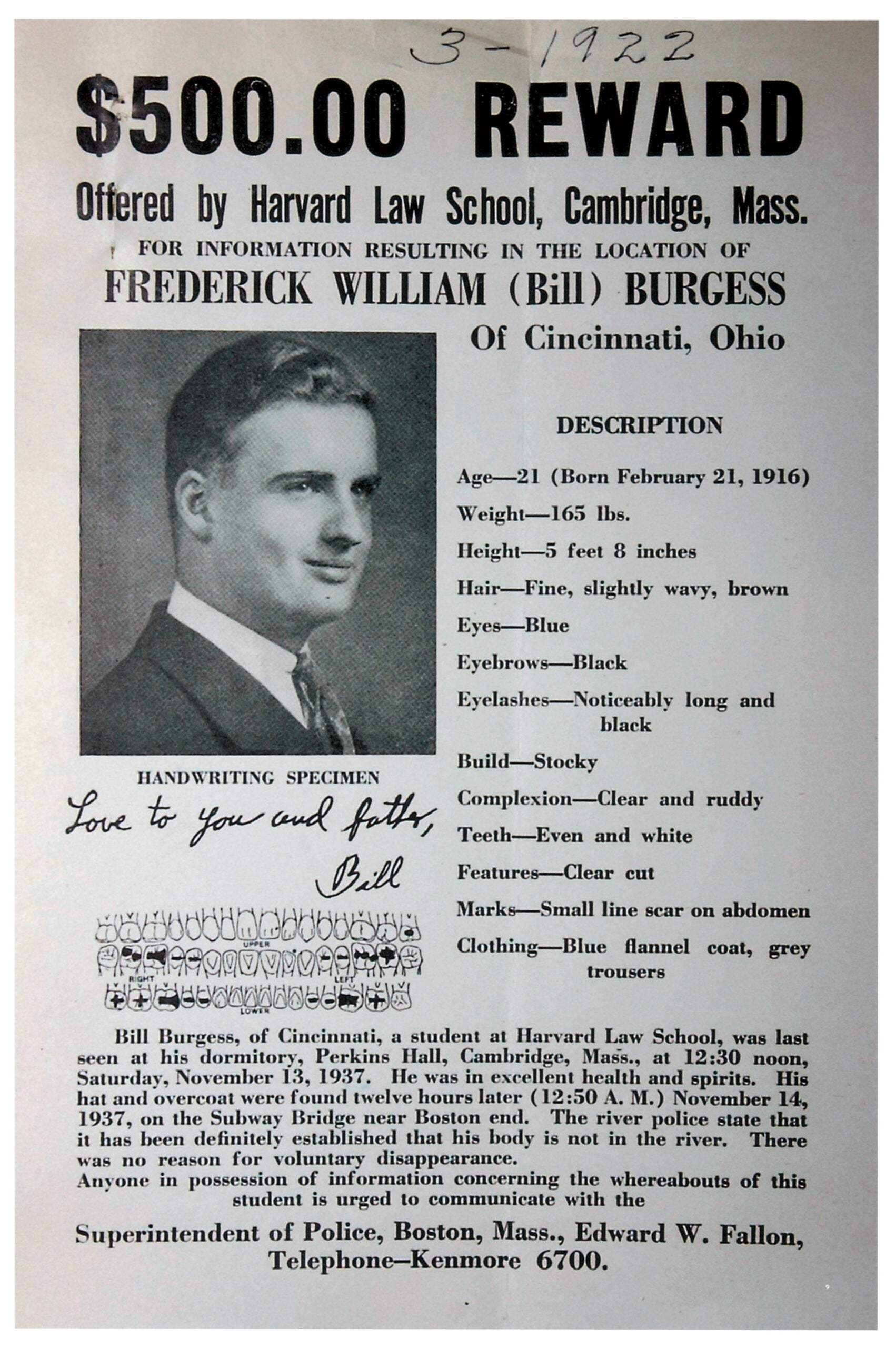

Within days, the slightly torn poster arrived in Smith’s Langdell library mailbox. It provided Burgess’ photograph, a handwriting sample, and a diagram of his teeth, but Smith had no hint of his fate.

* * *

As emergency floodlights illuminated the pre-dawn sky, Boston police power boats began dredging the Charles River for Burgess’ body less than an hour after his belongings were discovered.

Police at first suspected that Burgess, who came to HLS after graduating from the University of Cincinnati the previous spring, simply jumped or fell 40 feet into the river.

Witness accounts supported both theories.

One woman claimed she saw a man through the mist and fog drowning in the Charles. Two others–including the night watchman at the Charles Street Jail–said they heard someone shouting for help that night.

Detectives thought they had a break in the case a week after the student vanished, when another person came forward and said a coworker saw a fight on the bridge around the same time as Burgess allegedly disappeared.

For days, police kept dredging the river with grappling hooks. But when Burgess’ body didn’t surface after two weeks, and the witness accounts unraveled, detectives began to wonder whether Burgess had fallen in the water after all.

The cries turned out to have come from a woman who was intoxicated. Detectives couldn’t find the alleged witness to the fight, and they didn’t believe Burgess would have neatly folded his coat during a scuffle or robbery.

* * *

From the outset, relatives and friends rejected suggestions that Burgess, whom they called Bill, committed suicide or purposely disappeared.

Foul play perhaps. Or even amnesia, they said.

After all, as the Crimson reported, Burgess was in good health, performed well during his first semester, and didn’t have any trouble with women friends. Only a week before, his mother said she received a “sincere, happy message” from her son.

And on the morning of his disappearance, he joked with a janitor, tended to his newly laundered clothes, and talked with friends in an adjacent dorm room about the Pittsburgh-Nebraska football game.

“Burgess was always a cheerful fellow and he was in good spirits Saturday,” one Perkins Hall friend told the Boston Herald soon after he vanished.

With little progress being made by Cambridge police, Burgess’ parents pressed for outside assistance in December. They enlisted a diver who searched the river floor within 800 feet of the bridge for two days. He reported finding a perfectly smooth river bottom and suggested there was no possibility Burgess’ body rested in the Charles.

Burgess’ mother then met with FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover in Washington, D.C. He agreed to investigate the case on the theory Burgess’ disappearance involved an interstate crime.

Soon after New Year’s Day in 1938, the FBI’s New England regional director, William J. West, ordered law enforcement agencies nationwide to check local morgues for unidentified bodies and search hospitals for amnesia victims.

At the same time, the Law School announced the $500 reward for information about Burgess’ disappearance and began distributing 70,000 flyers to police departments throughout the country.

“The river police state that it has been definitely established that his body is not in the river,” the flyer declared.

* * *

Sightings began trickling in within a week of the reward announcement.

Harold Ball, a Bluefield, W.Va., newspaper reporter, wired Boston police and claimed he saw Burgess eating lunch in a local restaurant. Ball said he found a “Mr. Burgess” registered at a nearby hotel as a representative of a Cincinnati firm but could not locate the guest.

Then two Bluefield women reported that a man who looked like Burgess sought lodging and meals at their boarding houses.

But a week later, Bluefield Police Chief C. N. Wilson told the Crimson that Burgess was not in his town. “I don’t think he has ever been here,” Wilson said.

On January 12, a Cambridge contractor, Robert Capella, came forward to say he saw a man struggling in the water on the morning of Burgess’ disappearance. Capella told the Crimson that as the man went down for the last time he heard him shout, “I don’t want to die.”

Four days later, three people in Radford, Va., claimed the picture of Burgess matched the young man who showed up at their doors to sell magazine subscriptions.

Mrs. W. B. Thurman claimed the young man said he was a “sophomore in law school in Massachusetts” and was working in all the big cities between Boston and New Orleans to earn enough money to return to school.

* * *

As the ice breaker Francis cruised the Charles River on the morning of February 6, 1938, two teenage crew members noticed an object that looked like a buoy floating on the surface of the water. The two teens, William Foley and Charles Gilbert, rowed out to the object.

There, floating a mile from the bridge where his belongings lay discarded three months earlier, they discovered Burgess’ body.

Burgess was still fully dressed, wearing a blue and white striped tie bearing the label of a Cincinnati haberdasher. Inside the pockets of his blue-striped gray pants rested traveler’s checks, a Harvard bursar card, and a Harvard Coop card.

The medical examiner could positively identify his remains only by matching his teeth with dental records. The doctor who performed the autopsy reported death was accidental and that Burgess’ backbone was broken by a fall.

Articles detailing the discovery appeared in the New York Times and on the front pages of all the daily newspapers in both Boston and Cincinnati.

For Burgess’ parents, though, the high-profile discovery brought little solace.

“Even if the suspense is over, the case remains a mystery to us,” his father, Frederick A. Burgess, told a Cincinnati newspaper.

In June 1939, an article titled “What Can We Believe?” and signed by “Bill’s Mother” appeared in the Atlantic Monthly magazine. Burgess’ mother later told the Cincinnati Enquirer she authored the article after first writing it as a letter to three of her son’s close friends.

“I am wholly unable to answer your questions. They are my questions too,” she wrote. “Let us not make of Bill a stranger because of his strange death.”

* * *

Forty-two years later, CSX Railroad Police Special Agent Jim Fisher was cleaning out old police files in Florence, S.C., when he came upon a pile of discarded wanted posters. In the stack, Fisher found Harvard Law’s reward flyer for Burgess.

Fisher took the flyer home and stored it in a box along with hundreds of other wanted posters he collected during his 28-year career as a police officer.

Last spring, Fisher decided to post the flyer on eBay. That’s when Smith, who is automatically notified any time a Harvard Law School-related item goes up for bid, received an e-mail.

Smith previously purchased a plate emblazoned with the image of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis and vintage postcards depicting Langdell and Austin Halls. But no online finds intrigued him quite as much as Burgess’ reward poster.

“I was very surprised,” Smith said. “I have never heard of a disappearance of a law student or the Law School offering a reward like this.”

So Smith entered the winning $26.57 bid and returned Burgess’ flyer to Harvard. How Burgess wound up in the river, though, remains a mystery.