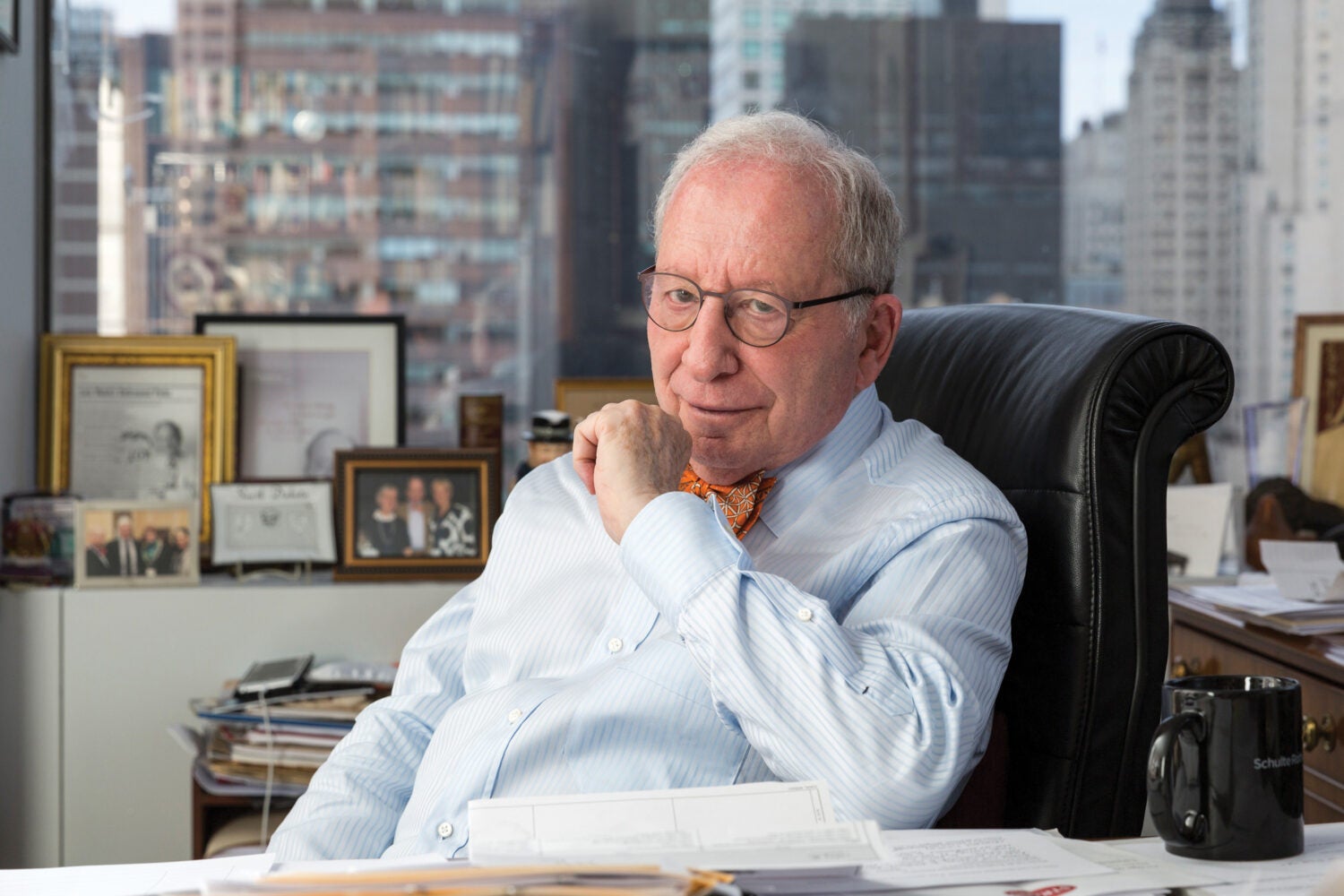

William D. Zabel ’61 has many reasons to be grateful. He has a loving family (his wife, Deborah Miller; their three sons, Richard ’87, David, and Gregory; and seven grandchildren) a successful and stimulating legal practice, and continues to advance causes he cares about. But he says he’s particularly grateful these days. And with good reason: He spoke to the Bulletin shortly after his release from a two-week hospital stay after contracting COVID-19 and fearing—more than once—that he would die while his family was barred from being at his bedside because of the highly contagious virus.

He has completely recovered, he says, and he is eager to experience more of a remarkable life of 83 years and counting.

“There’s a great serendipity in life that none of us can explain—and I’m happy to be a beneficiary,” Zabel said.

Just a few years out of law school, Zabel wrote an amicus brief for the ACLU in Loving v. Virginia.

His career has featured work on behalf of causes he believes in, starting when he was a young lawyer. As an associate with Cleary Gottlieb, Zabel spent the summer of 1964 in Mississippi as a volunteer civil rights lawyer with the Lawyers’ Constitutional Defense Committee to help with efforts to expand voting rights for African American residents there. Later, with the firm he co-founded in 1969, Schulte Roth & Zabel, he advocated for sometimes high-profile clients in his specialties of trusts and estates as well as family law. One of his first cases for the firm involved contesting the will of a wealthy New York businessman who had disinherited his daughter because she had married an African American man. It was a case made for Zabel, recalling his longtime advocacy to end anti-miscegenation laws that sprung from his time as an HLS student arguing a moot court case on the subject. When he learned that people of different races were barred at the time from marrying each other in 16 states, he was “appalled,” he said: “It struck me that how the hell in America could a man not marry a woman just because one was white and one was black.” By 1965, he had published an article in The Atlantic, “Interracial Marriage and the Law,” arguing against the constitutionality of U.S. miscegenation laws. He went on to write an amicus brief for the ACLU in the Loving v. Virginia case—in which the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in 1967 that such laws were unconstitutional. Zabel considers the Loving case and the creation of his law firm to be the two most important achievements of his legal career.

In addition, he has worked on behalf of international human rights causes, including traveling to Chile in the 1980s to examine cases of Chileans tortured and murdered during the Pinochet regime. He has served as board chairman for Human Rights First and the Immigrant Justice Corps, and has won recognition for his human and civil rights contributions including the Lawyers’ Committee for Human Rights Extraordinary Leader Award and the inaugural Robert F. Kennedy Justice Prize from the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law.

His passion for social justice developed during a childhood in South Dakota through the influence of his parents, who were politically active and supporters of Sen. George McGovern, a family friend whose public service inspired Zabel. Captain of his nationally contending high school debate team, he was, he jokes, argumentative from a young age and learned early on the importance of standing up for what is right, when his grandfather, a nonlawyer, took a neighbor to court for poisoning Zabel’s dog. Though harming a dog wasn’t a crime at the time, his grandfather obtained damages from the neighbor.

“I thought it was a great thing that the law could get justice even for a little dog,” said Zabel.

He has ensured that public service plays an important role at his firm, which hired a full-time partner to focus solely on public interest work. He has also helped build it into a thriving business, ranked by The American Lawyer as one of the 100 most financially successful law firms. In one of his most notable cases, he negotiated a settlement of $7.2 billion from the estate of his client, Jeffry Picower, an investor with Bernie Madoff, which returned money to the victims of Madoff’s Ponzi scheme in what Zabel calls the largest civil judgment against an individual in the history of American jurisprudence.

He has represented some of the wealthiest people in the country, including investor and philanthropist George Soros, whom he considers a friend. How does he advise such clients? Carefully, he says, and with a high degree of—no pun intended—trust required.

“When you’re advising someone on that level and on a personal basis, you become almost a quasi-psychiatrist,” said Zabel. “You really get into their personal values, lives, private interests. They expect loyalty, as do all clients, and discretion is especially important to the very rich.”

Somewhat by happenstance, Zabel also became a prominent divorce lawyer. The founders of the firm didn’t envision that family law would be part of its practice, but he took his first case in the field in order to represent a secretary in the firm against a well-known divorce lawyer. That led to recommendations for other cases, and Zabel went on to represent Jane Welch, in divorce proceedings against former General Electric CEO Jack Welch; golfer Greg Norman; and radio personality Howard Stern, among others.

Zabel credits Harvard Law with helping to facilitate his financial success and recently gave back to the school in the form of an endowed professorship in human rights. (Professor Samantha Power ’99 was named the first recipient, to his great delight.) Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor sent remarks paying tribute to Zabel during a celebration of the professorship at the school in late February, which read in part: “Your unceasing devotion to human rights and to fighting injustice spans more than a half century. … You have remained true to the lawyer’s responsibilities to help secure a just world.”

In his own remarks at HLS that day, Zabel quoted Winston Churchill, whom he frequently turns to for inspiration, citing the aphorism “Success is never final.” He ended his speech with poetry—a passion of his that he has been known to incorporate into his legal writing—reciting a portion of the poem “Ulysses,” by Alfred Lord Tennyson, including:

Old age hath yet his honour and his toil;

Death closes all: but something ere the end,

Some work of noble note, may yet be done …

“Ere the end,” Zabel would like to inspire lawyers to do public service, which he says is more important now than ever. And he is still as excited as he always has been by the law, as evidenced by the fact that soon after his recovery this spring, he took on more work for his firm. He could be living a very comfortable retirement now, but lying on the beach or playing golf doesn’t interest him. Besides, his work helps keep him young, though he quips that it’s hard to stay young when you’re old.

“I really enjoy practicing law. I think I do it quite well,” he said. “Experience is of great value in the law.

“I think I’m still at the top of my game when I need to be.”

And like Ulysses, he is still looking to do more.