For weeks after the attack on the Capitol Building on January 6, 2021, Alan Jenkins ’89 found himself waking up in a cold sweat at 4 a.m., worrying about the future of American democracy.

A professor of practice at Harvard Law School who teaches courses on race and law and Supreme Court jurisprudence, Jenkins fretted about the disinformation and disrespect for democratic principles that led to the assault on the U.S. Capitol, and he feared subsequent efforts by some to rewrite the history of what transpired that day — casting the rioters as “patriots” and dismissing violent behavior as “peaceful protests.”

“I already saw the public discourse moving away from what had happened and minimizing it and, in some instances, trying to retell the story,” said Jenkins. “As somebody who teaches among other things about the Reconstruction Era in our country, I’ve seen this story before,” said Jenkins, noting what he said were “concerted efforts” after the Civil War to recast the rebellion as “a mythology of the Lost Cause.”

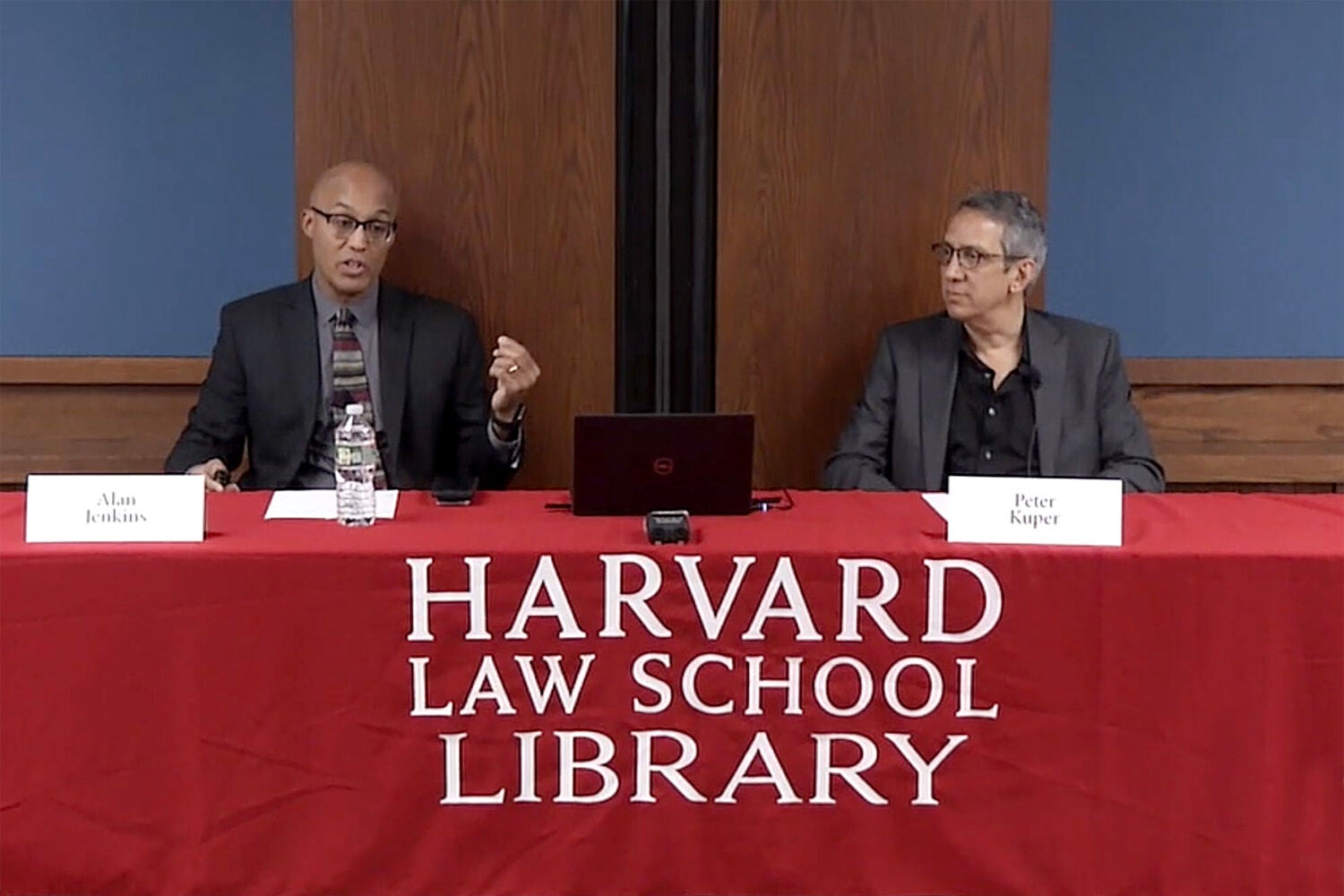

At a Harvard Law Library book talk on Oct. 25, Jenkins discussed the graphic novel series, “1/6: The Graphic Novel,” he created with graphic novelist Gan Golan and illustrator Will Rosado. Cartoonist, illustrator, and visiting lecturer on film and visual studies at Harvard University, Peter Kuper joined Jenkins at the Harvard Law School event to discuss the history of comic book culture.

Jenkins, a self-described “comic book guy,” said he created the series as a way of inspiring a broad audience to engage with democracy in the face of threats to free and fair elections.

“Popular culture has always really been a very important change strategy,” said Jenkins, who most recently served as founder and director of The Opportunity Agenda, a nonprofit that develops communication strategies for social change.

“We’re in a comic book moment in our culture, for better and for worse. Almost all of the biggest blockbuster movies for the last 15 years have been based on comic books,” he said. “The thing about the comic book medium is that if you’re 80 years old in the United States, you grew up on comic books and if you’re eight, you’re growing up with comic books.”

Designed as “dystopian speculative fiction,” the four-issue graphic novel series draws on real-life events to imagine what America could have looked like if the Jan. 6 insurrection had succeeded.

With the aim of reaching people who may not have “read the 800-page report” from the House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the U.S. Capitol, Jenkins worked closely with Harvard Law research assistants Emily Miller ’24 and Jennifer Zhang ’23 to “painstakingly” examine the details of what actually happened, drawing from interviews, indictments, and other court documents.

Volume 1, which debuted in January 2023, features an alternative scenario in the aftermath of the insurrection in which the Capitol rioters are prominently celebrated and the president declares martial law, deputizing the Proud Boys and Oath Keepers. The second issue, due out in the coming weeks, flashes backward to the events leading up to Jan. 6, 2021. Volumes 3 and 4 will explore the implications of the insurrection.

The series features four characters, whose ideologies span the political spectrum, who eventually come together to try to restore democratic norms.

“We wanted to bring empathy to all of those characters,” he said. “There are some bad guys in this comic book, but we felt that recognizing the humanity in all of our main characters, even ones who we would not agree with in real life, was really important — both for a compelling story and also to bring in people who might otherwise be dismissive of the story itself,” said Jenkins.

The comic genre has a long history of tackling themes related to social justice and inequality, and challenging authoritarianism, said Jenkins, sharing images from a collection of comics, including an image of Black Panther fighting the Klan, Captain America hitting Adolf Hitler in the jaw in an issue that came out several months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and another of Superman grabbing Hitler and taking him to the International Court of Justice, which did not exist at that time.

Kuper, whose work appears regularly in The New Yorker, The Nation, and Mad Magazine, where he has written and illustrated “Spy vs. Spy” since 1997, said comics as a form of visual storytelling have a rich history. “It’s in our DNA,” he said.

“Our first language really is pictograms,” he said. “There’s the codexes [ancient manuscripts] that have characters and they read basically like a comic book.” In religious contexts, he noted, stained glass windows in churches depict “a sequential narrative, recurring characters.”

He shared a wide array of images of artists depicting political and social justice issues, from Honoré Daumier’s caricature of French King Louis Philippe, Thomas Nast’s depictions of the corruption of New York machine politician Boss Tweed, and Jacob Lawrence’s migration series, illustrating the mass movement of Black Americans from the rural South to the urban North.

“Throughout our history, artists have been trying to capture what’s going on politically,” said Kuper.

In the 1950s, during the McCarthy period, there was a backlash with a number of books being banned and burned. EC comics was among the few that survived, said Kuper, in part because they transitioned to a magazine, referring to Mad Magazine, where he worked for 27 years.

“One of the things that came out of Mad was the influence to create underground comics,” he said, pointing to a number of recent award-winning graphic novels — from Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” to Marjane Satrapi’s “Persepolis” and Joe Sacco’s “Footnotes in Gaza.”

His 1/6 graphic novel is designed to be entertaining, Jenkins said, “Nobody likes a lecture.” But, along with the book, he also provides a roadmap for action.

“Most people perhaps will read the series when it’s done, and, you know, hopefully enjoy it and go on with their lives,” he said. “But for some percentage of those people, we felt that they might be interested in actually taking action to protect our democracy to combat bigotry, and hate and disinformation, we want to give them a way to do that.”

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.