A project by Harvard Law School’s Dispute Systems Design, or DSD, Clinic is helping address a pressing justice issue in Brazil — the forced removal of vulnerable communities from occupied land. This October, students and instructors from the Dispute Systems Design Clinic travelled to Paraná, Brazil to meet their client, the Brazilian National Council of Justice.

The project came to the DSD Clinic by way of a recent Harvard Law graduate, Carina Nicoll Simoes Leite, LL.M. ’23, who is currently clerking for Justice Luis Roberto Barroso, the president of Supreme Court of Brazil. Leite connected with Ana Carolina Viana Riella, outreach and case coordinator at the Harvard Mediation Program, at a Harvard Law event Viana Riella moderated last year. The two began discussing the project and soon looped in federal Judge Fabiane Pierrucini of the Brazilian National Council of Justice, who is tasked with developing and scaling the innovative mediation program being studied by the clinic’s students to a national level — Viana Riella knew Judge Pierrucini would be a great client for the Dispute Systems Design Clinic.

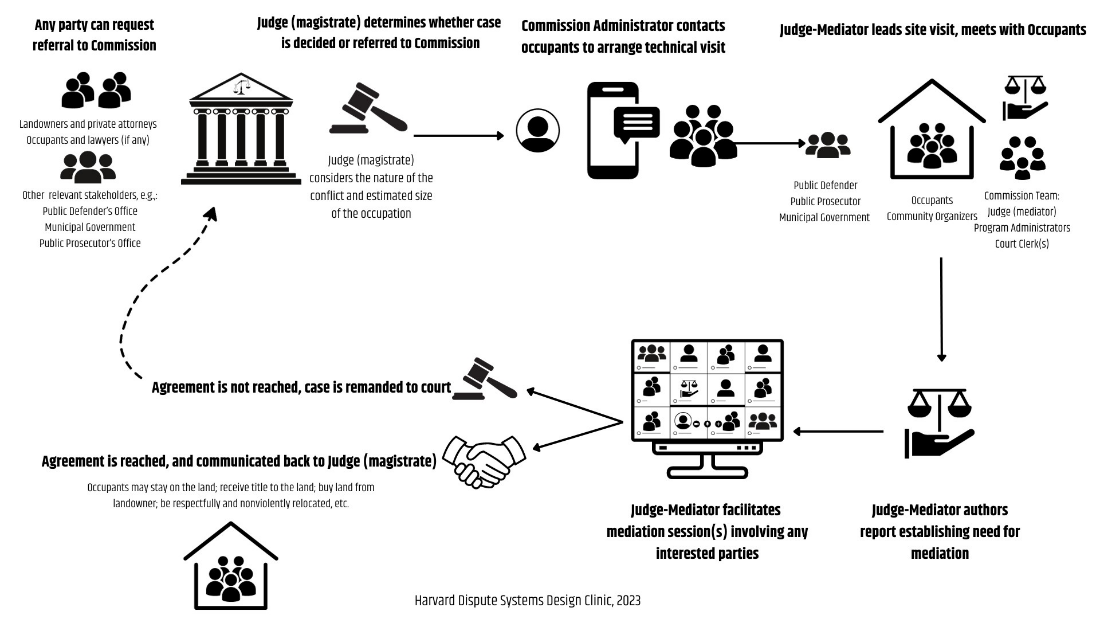

The impetus was a 2021 Brazilian Supreme Court decision requiring states to resolve collective land disputes through mediation rather than litigation. Such cases involve large groups — sometimes hundreds of families and thousands of people — occupying land owned by private entities or the government. Previously, landowners could enforce titles to evict occupants; in practice, defendants in many cases were unaware a lawsuit had been filed or decided until the moment the state appeared on site to forcibly remove them. This process often resulted in violence and mass displacement of individuals. After several prominent forced removals, advocates called for reforms to prevent further human rights abuses. The state of Paraná pioneered a successful mediation program, which the recent Supreme Court decisions requires every state to replicate. This mandate represents uncharted territory for most judges.

That’s where the DSD clinic comes in. Under the umbrella of the Harvard Negotiation and Mediation Clinical Program, the clinic works with organizations and communities to help them navigate conflict management challenges effectively and equitably. “With the Supreme Court decision that requires every state in Brazil to develop a program like the one that originated in Paraná, there are a lot of questions about how such programs should be designed and tailored to the human and environmental needs of different regions. There is also the question of supporting and training federal judges as they take on the role of ‘mediator’ for the first time — a role new to many of them,” explains clinical instructor Deanna Pantín Parrish ’16.

A team of her students has spent the fall semester tackling these questions. Chloë-Arizona Fodor is a student at Harvard Divinity School who cross-registered into the DSD clinic, finding a perfect alignment between this project and her studies, which focus on transferring interpersonal skills such as alternative dispute resolution to institutional levels, particularly relating to ancient Jewish religious law and modern Israeli military law. She’s been thrilled to get hands-on experience applying her studies into practice.

“We’ve been really getting our hands dirty, carrying a lot of the initiative and work with the project,” she says. “The work that we do as students in the clinic is highly relational. We deal with client interface, doing things like scheduling meetings, making sure agendas and follow-up communications are done on time. We’re doing all of our primary and secondary research. We’re conducting interviews with the judges and stakeholders in Brazil, community members in these land settlements, prosecutors and public defenders, and administrators within the system. We’re developing surveys to get a wider range of information from stakeholders in the system.”

Mediations such as the model set by Paraná are open to all relevant stakeholders who want to have their voices heard in the resolution of the particular dispute. In practice, these conversations can involve the landowner(s), many occupants — whose collective views are often represented informally by community organizers, public defenders, and private attorneys — providing formal counsel and representation to relevant parties, representatives from the municipal government, housing officials, and community leaders, to name a few. While not all these stakeholders are parties to the formal legal case, this innovative model rests on the promise that they may each be integral to constructing an alternate solution during mediation.

Once a case is referred to the process, the judge who will serve as mediator conducts a site visit to the affected community and meets with occupants on the ground. This serves as a fact-finding step through which the judge seeks to understand the size and longevity of the occupant community, in order to estimate the impact of their removal. For example, some communities have been present on the land in question for decades, with occupants having only ever lived on that land for their entire lives. The mediation itself then follows, taking place online over the course of days or weeks, in a process that sometimes continues for several months. Pantín Parrish explains the approach is intended “to prevent human rights abuses that may come from the violent displacement of individuals, as well as to help support occupants move, if necessary, nonviolently, equipped with resources.” This novel approach found success in Paraná; the clinic is considering how the process can be scaled up throughout the entire country of Brazil and how Brazilian judges can be adequately trained to take on mediator roles.

While students tackled this work in Cambridge, they simultaneously prepared for their trip to Brazil to become further immersed in the work. “We read background research about Brazilian mediation, the cultural context in which the Brazilian courts are situated, and the political environment of Brazil, as it relates to alternative dispute resolution,” Fodor describes.

The on-the-ground experience was transformative. “Despite watching videos and seeing images of it, you really understand the full scale once you’re there,” says Viana Riella. “It brings you back to one of the points of the process — for judges to be there on site themselves before the mediation. There is no way of understanding this on paper. Once you see the reality and you step into the area, it gives you a whole different understanding.”

“Injustice looks really different up close than it does in a textbook,” adds Pantín Parrish.

Fodor was thrilled to connect in person with counterparts from the Brazilian National Council of Justice. “From the beginning, even over Zoom, I felt like we established a good relationship, and then being able to go to Brazil and meet the client and the team that’s working over there was an incredible experience. I truly feel that the relationships that we established there during the time we were there are going to allow the relationship between the Dispute Systems Design Clinic and the Brazilian court system to continue even after the project is done. We were able to connect with judges within the commission of land issues in Brazil and talk to their interns that are about our age, who are doing a lot of heavy lifting there also.”

Over the course of their five days in Brazil, the clinic team was able to attend on site visits with judges to settlement communities, observe online mediations, and interview stakeholders.

“If a central tenet of dispute systems design work is to tailor a system to the people who are impacted by it, you have to have access to the people who are both impacted by and administering the system, and the fact that we had such open access to stakeholders across the process was a true gift,” says Pantín Parrish.

“We are extremely grateful to everyone in Parana’s Justice Tribunal for allowing us that access as well as the generosity with their time and attention. The trip was meaningful. It was complex. It was intense and inspiring. And I don’t think we could have done this project without it. That’s what experiential learning is all about,” adds Viana Riella.

“Going to Brazil was something truly powerful and meaningful,” echoes Chiara Fargnoli. “Having the opportunity to go on the ground and personally engage with the stakeholders involved benefited our understanding of the situation. It gave us a deeper insight into the challenges and obstacles that hinder us from accomplishing our final product. We got to see what reality is like for the affected community, which even though was heartbreaking, gave me a further boost and motivation to fulfill our mandate.”

“The clinic, and especially the time in Brazil, really demonstrated to me firsthand just how crucial interpersonal relationships are and good faith implementation is when we’re talking about mediating multi-party land disputes with vulnerable populations,” reflects Fodor. “It requires a humanist approach that ends up serving the entire system and all those who are involved in it. It’s so important to ensure that good faith implementation is occurring in mediation.”

The project epitomizes how Harvard Law School’s legal clinics tackle complex justice dilemmas using immersive experiential learning. Pantín Parrish acknowledges that solutions will be imperfect but hopes that they will help move the needle towards greater justice: “The students have been grappling with really complex questions for which there are no easy answers. And that’s so much of what justice work is.”