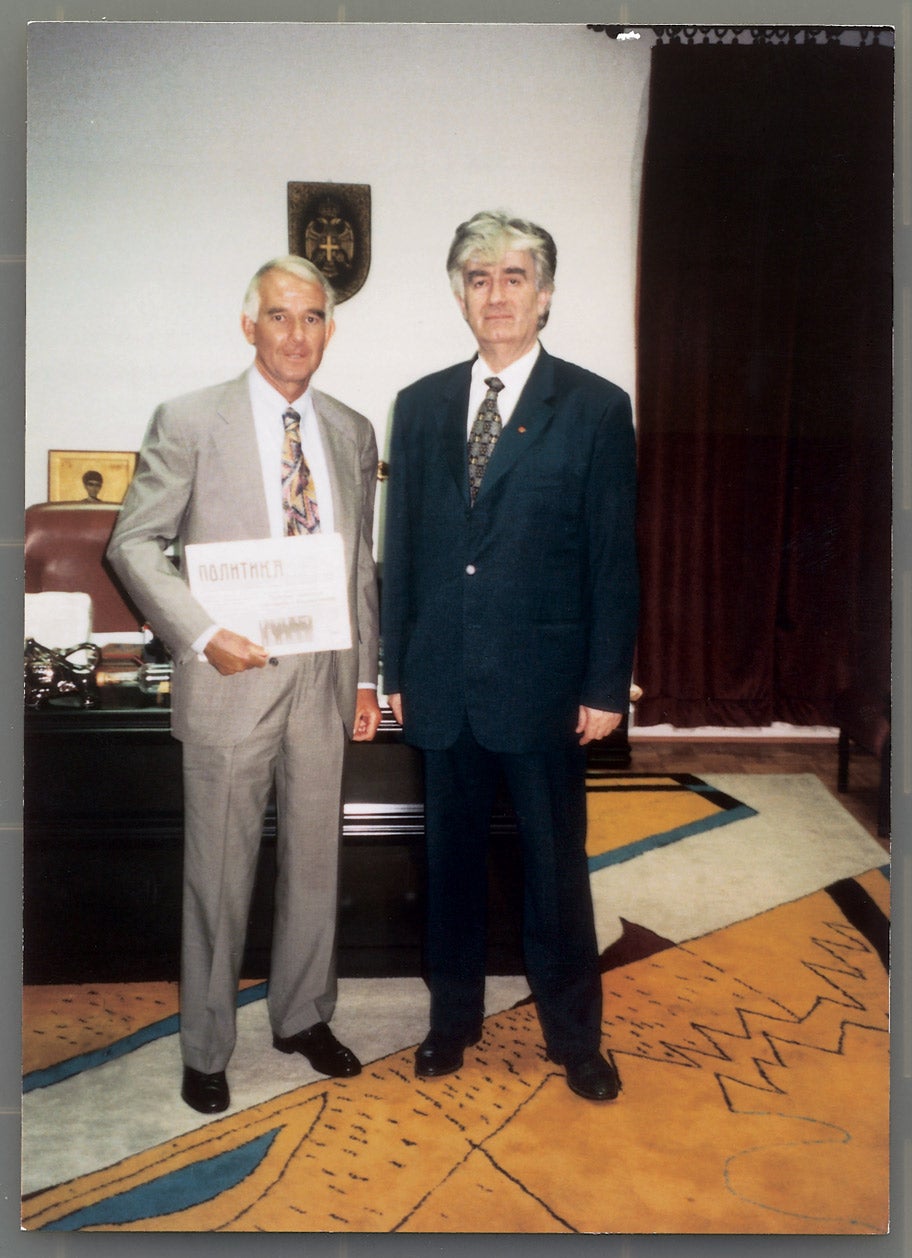

In 30 years of practicing law, corporate bankruptcy attorney David Erne ’68 had been in many negotiations–but none like this one. Bosnian Serb wartime leader Radovan Karadzic was hiding in the mountains of Bosnia. Karadzic had been indicted for war crimes he allegedly committed during the civil war in the former Yugoslavia. The U.S. government wanted him to surrender and face trial in the Hague, but Karadzic was unwilling to give himself up.

Erne thought he might be able to broker a solution. Although he is not Serbian, his wife is. He had been active in the large Serbian-American community in his hometown of Milwaukee, and in 1994 he had written a history of Yugoslavia for the United Nations War Crimes Commission.

“Because my wife was Serbian and I had traveled there a lot, [the Serbs] were trustful of me,” Erne said. “From the perspective of the State Department, they trusted me because I was American.”

For several days in the summer of 1997, Erne engaged in shuttle diplomacy between Karadzic’s hideout and the U.S. Embassy in Sarajevo. During the negotiations, Erne stayed at a hotel in the mountains above Sarajevo. The hotel, which had originally been built for the 1984 Winter Olympics, was now deserted and Erne was the only guest. Late at night a car would come and take him to another location, where he would meet with Karadzic. The next day he would travel to the U.S. Embassy and report on the progress of his negotiations.

In the end, Erne’s efforts proved unsuccessful. “Karadzic wanted the trial to be in Sarajevo and he wanted a Serbian jury, and that was just not going to happen,” Erne said. In fact, at the time of this writing, Karadzic is believed to still be somewhere in the mountains of Bosnia. “There are rumors that he has grown a beard and is dressed like a priest. It’s almost like Elvis sightings,” he said.

In 2001, Erne returned to Bosnia to help the country rebuild. He served as a consultant to the prime minister of Republika Srpska, one of two republics within the nation of Bosnia-Herzegovina. He worked down the hall from the prime minister and earned the same salary–$400 a month.

His activities included privatizing state companies, obtaining loans from Western lenders, and drafting legislation. His expertise in corporate bankruptcy law proved particularly relevant to the privatization work. “Bankruptcy was helpful because virtually every company there was bankrupt,” Erne said.

One of Erne’s privatization projects was the Biroc Aluminum Foundry, which once employed 5,000 people and was one of the largest aluminum foundries in Europe before it closed down during the civil war. He led the negotiations for the sale of the foundry to a Lithuanian investor. The planned reopening of the foundry will reduce the republic’s unemployment rate, which currently stands at 50 percent, and will also help create a tax base for the new government.

Now back home in Milwaukee, Erne continues to consult with the Republika Srpska government via e-mail. He says he never imagined that his experience as a business lawyer and his connections to the Serbian community would ever come together in the way they did.

“I had hoped at some point in my life to find a way of using my good education and lifetime of experience to help other people,” said Erne. “I just didn’t know that this is what would become available.”

–Timothy Kiefer ’98