For decades, Alan M. Dershowitz has led a frenetic life as author of dozens of books, legal counsel to a multitude of celebrities and ubiquitous TV commentator on myriad issues of the day.

But he’s held only one actual job: his professorship at Harvard Law School. And at the end of the year, he’ll be giving that up.

“Actually, I don’t think of myself as moving into retirement,” said Dershowitz during an interview with the Bulletin. “I’m just changing jobs—and it feels a bit strange to me. We’re a very mobile society in this country; people change jobs very quickly, but I’ve had the same job for 50 years.”

He anticipates doing even more writing and spending much more time with his family while winding down his other activities, but he still thinks more of beginnings than of endings.

“It’s hard for me to think that my career at Harvard is coming to an end. It’s been a good run, but to everything there is a season.”

“I was always the youngest person everywhere I went. I was the youngest assistant professor, the youngest full professor, the youngest this and the youngest that. Now I’m among the oldest, and it’s hard for me to think that my career at Harvard is coming to an end. It’s been a good run, but to everything there is a season.”

In October, HLS hosted a tribute to Dershowitz, featuring an array of friends and colleagues. The same month, “Taking the Stand: My Life in the Law” was published by Crown. It’s his most fully autobiographical book, and in large part an attempt to identify the people and institutions that influenced him the most over the course of his life.

He describes a childhood in Brooklyn, where his mother strongly encouraged his natural intellectual curiosity while the teachers and rabbis at the yeshiva he attended did not.

“You would think the opposite, that a Jewish background would encourage argument—after all, the Talmud is very argumentative—but the religious education I got did not encourage disputation. But when I got to secular school, it was encouraged and I thrived.”

His first secular school was Brooklyn College, followed by Yale Law School, where he would finish first in his class.

The first person to make a big impact on Dershowitz’s life in the law was Judge David L. Bazelon, chief judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, for whom Dershowitz clerked.

“Bazelon became my first real father figure professionally,” Dershowitz said. “He showed me that you could be both Jewish and mainstream at the same time—he was a very influential person in Washington but didn’t give up his Jewish heritage—and I wanted to be like him.”

He then took a second clerkship, with U.S. Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg, and, among other tasks, drafted the opinion in Escobedo v. Illinois, which held that criminal suspects have the right to legal counsel during police interrogations.

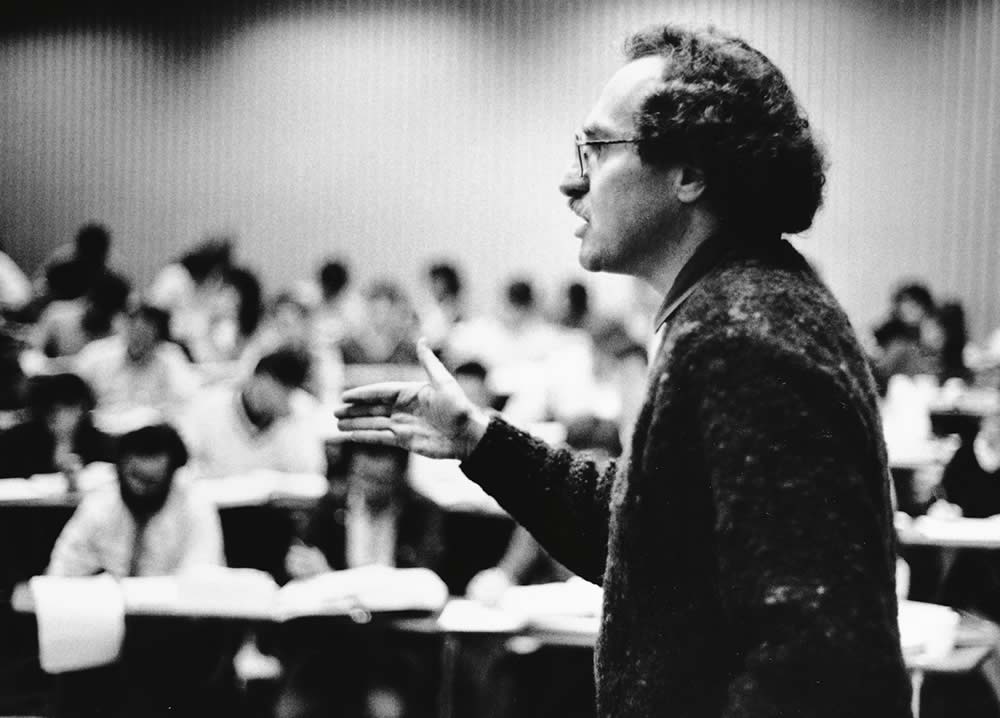

By then, Dershowitz had set his sights on criminal and civil rights law and was hired by Harvard during his Goldberg clerkship based largely on his academic record. He began in 1964 and immediately attracted attention.

“I was very Jewish in my attitudes and my style, and that made some people uncomfortable.”

“I was very Jewish in my attitudes and my approach and my style, and that made some people uncomfortable—particularly some of the faculty members who were themselves Jews and trying hard not to be Jewish. And I let it all hang out.”

After a few years, Dershowitz felt the need to gain practical courtroom experience and took on cases, often in association with the American Civil Liberties Union, involving challenges to censorship and the death penalty.

“It created a great combination,” he said. “I never missed classes for cases, and I was able to bring the courtroom into the classroom and the classroom into the courtroom.”

Over the years, Dershowitz has won 13 of the 15 cases he’s handled involving murder and attempted murder; his clients have included Claus von Bulow, Mike Tyson, Patty Hearst and Jim Bakker. And he’s become a frequent commentator as a staunch defender of Israel.

Reflecting on his career as a practicing lawyer, Dershowitz said his biggest contribution has been “convincing a skeptical American public that when you win on appeal, it may actually prove that there was an injustice.”

Asked what aspect of his career has provided him with the most personal satisfaction, he is unequivocal: “Teaching. Teaching is enduring,” he said. “The students don’t remember the specifics I taught them, but they remember the way in which I approached problems.”

Although Dershowitz is leaving teaching, he wants to stay forever connected to the school. He said some of his former students are seeking to create a chair in “humanitarian law and repairing the world” in his name.

“It would be very nice to have a permanent chair at Harvard Law School supporting the kinds of things that I’ve supported over 50 years: human rights, humanitarian law, support for the underprivileged, and seeing the law in a constructive and creative way.”