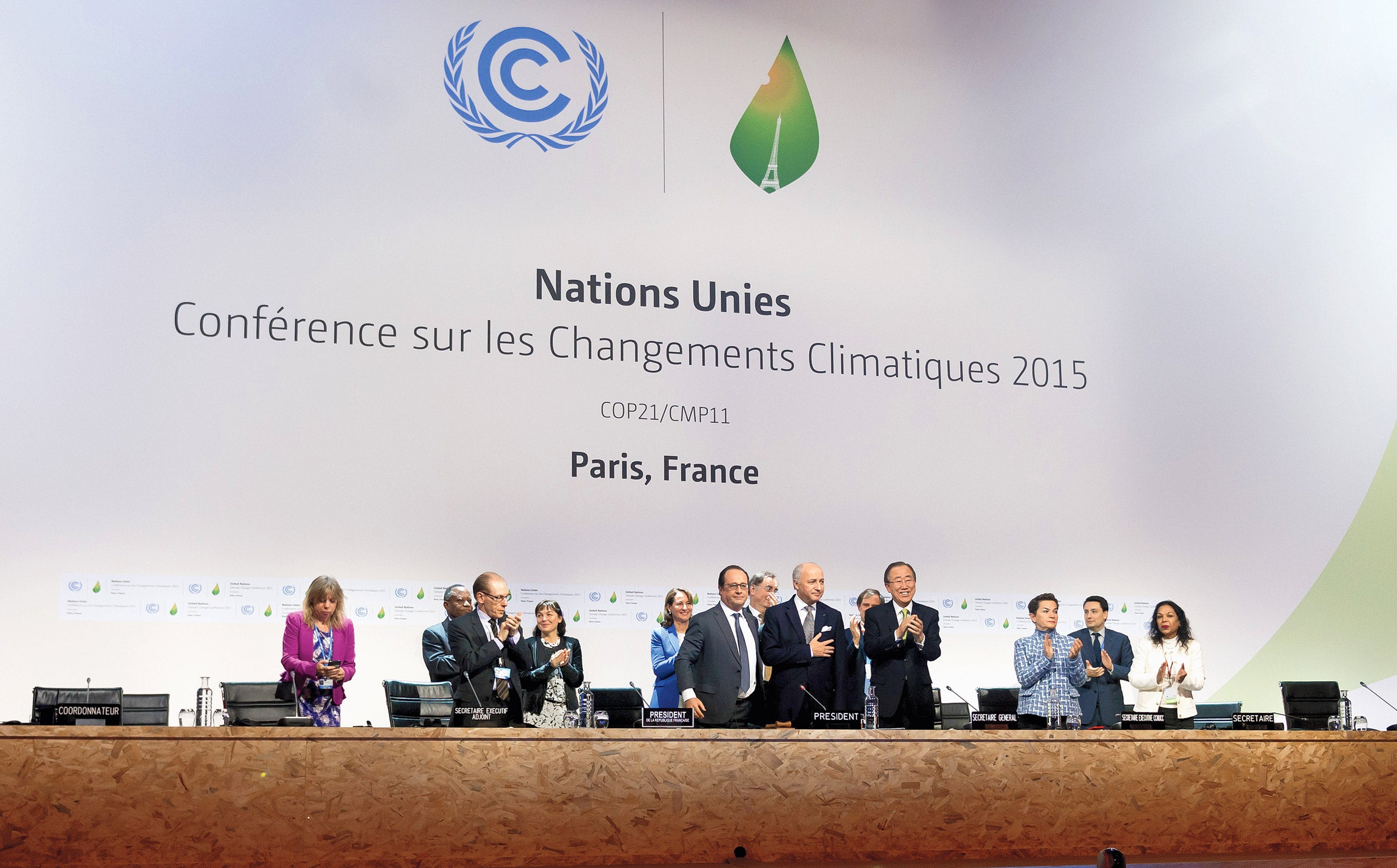

Two decades of work by Todd Stern ’77 to combat climate change was about to come to fruition last December in suburban Paris, where 195 countries had reached a landmark agreement to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

Then Stern, at the time the State Department’s chief climate change negotiator, started reading the final agreement text and noticed something was wrong. A key passage said developed nations “shall” reduce emissions rather than “should,” as in previous drafts. The change threatened to unravel a deal that hinged on each country deciding for itself how deep to cut emissions.

For 90 minutes, Stern—along with his boss, Secretary of State John Kerry, and other top U.S. officials—huddled with key foreign counterparts, successfully preventing a single word from derailing the agreement.

The error proved to be the last obstacle among so many in the 18 years since Stern joined a Clinton administration team preparing for an earlier round of talks in Kyoto, Japan.

In the intervening years, Stern played a pivotal role in developing the U.S. approach and ultimately quarterbacked the efforts of President Barack Obama ’91 to reach a climate deal.

“Todd has been creative, flexible and steady as a rock,” said HLS Professor Jody Freeman LL.M. ’91 S.J.D. ’95, who served as Obama’s top climate change adviser in 2009-2010. “He deserves a lot of credit.”

Environmental law and international diplomacy didn’t figure early in Stern’s career. He started out as a legal aid attorney and then shifted to corporate law at Paul Weiss before realizing he “had an itch for more public-minded and political” work.

He worked on the presidential campaigns of Michael Dukakis ’60 and Bill Clinton and then as White House Staff Secretary John Podesta’s deputy before replacing him in 1995. It was in that role, Stern says, that he cut his teeth on climate change, when he was asked to work with a group preparing for the Kyoto conference.

“I learned that the multilateral climate process was very acrimonious, with a sharp divide between developed and developing countries, and that it was really difficult to have calm and reasoned exchange of ideas in the setting of the big year-end conferences, which are fairly chaotic and cacophonous, with literally thousands of players,” Stern said of his experience in Kyoto and the following year in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

On the 13th day of what was intended to be 12 days of negotiations, Stern finally thought to himself: “Oh my God, we’re going to get this done. After all these years, this is actually happening.”

The Kyoto agreement adopted in December 1997 mandated binding reductions in carbon emissions for developed countries, but it included no mandatory standards for developing countries. The Senate never ratified the treaty, and President George W. Bush withdrew from the accord entirely soon after taking office.

Stern thought a lot about what went wrong both substantively and politically with the Kyoto agreement during the Bush administration, while a partner at WilmerHale and a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress.

“What is enshrined in Kyoto is a quite stark division between developed and developing countries with everything targeted at developed countries, and developing countries weren’t asked to do anything,” Stern said. “From a substantive point of view that can’t work, and from a political point of view there just wasn’t support for an arrangement in which China and other big players were not being asked to do anything.”

Stern had an opportunity to apply those lessons when Secretary of State Hillary Clinton named him her chief climate change envoy in January 2009.

He got his first sense of how much global counterparts welcomed the Obama administration’s engagement at a conference in Bonn, Germany, in March 2009, when hundreds of attendees gave him a standing ovation.

“I told him, ‘Enjoy it. That’s the last standing ovation you’re going to get. Now you have to deliver the goods,’” said Alden Meyer, director of strategy and policy at the Union of Concerned Scientists.

The initial euphoria had worn off by the time 115 world leaders gathered in Copenhagen, Denmark, nine months later. The talks ended without any agreement to reduce emissions, but they helped lay the groundwork for later success in Paris, Stern said.

Still, Copenhagen represented a low point for the Obama administration’s efforts to reach a deal, particularly when it came to relations with China, which felt unfairly blamed for the outcome. (A Chinese negotiator called the U.S. a “preening pig” at one subsequent bilateral session.)

Stern said he wanted to make sure the two nations were “more synced up next time” and set out to develop a stronger relationship with his Chinese counterpart, Xie Zhenhua, during dozens of formal meetings and more informal interactions.

He traveled to Xie’s hometown in China, took him to a Cubs game in Chicago, and hosted a dinner at his home with his wife and sons.

“I don’t want to overdo it: Countries act based on interests, not because their guy likes our guy,” Stern said. “On the other hand, it’s also true that if you build trust between two people who are dealing with each other and build some affection on top of that trust, you’re going to have a better chance of finding common ground.”

Stern’s outreach and months of quiet negotiations helped lead to a joint agreement in November 2014 between the U.S. and China to curb carbon emissions, a step—along with multiple layers of other bilateral and multilateral negotiations—that helped pave the way to the Paris deal.

“Todd was the day-to-day quarterback calling the plays and giving the signals,” Meyer said. “People in the administration gave a lot of deference to Todd on negotiating dynamics, where other countries’ redlines were, where their sweet spots were, and how to get to yes.”

Roger Ballentine ’88, president of Green Strategies, who succeeded Stern as the Clinton administration’s climate change coordinator, recalled another hallmark of Stern’s success that he witnessed during an earlier round of hostile talks with China’s negotiators in the 1990s.

“Todd was just steady. He wouldn’t let them leave the room. He wouldn’t get emotional. He just kept driving through that meeting with patience, perseverance, and a relentless but polite way that ultimately led to a very long and productive meeting because of his refusal to let the meeting go south,” Ballentine said. “That kind of patience and determination served him very well when he ultimately did the Paris negotiations.”

Stern said it wasn’t at all certain that a deal was going to happen in Paris until the 13th day of what was intended to be 12 days of negotiations. “I remember sitting in my seat, thinking, Oh my God, we’re going to get this done,” Stern said. “After all these years, this is actually happening.”

Under the Paris accord, nearly every country—both developed and developing—agreed to lower greenhouse gas emissions, with each country determining its own targets. But countries will be legally required to monitor emission levels and report publicly on a regular basis on the progress of their efforts and on whether cuts meet their targets.

“We accomplished a great deal and indeed, honestly, more than we even expected,” Stern said at a Brookings Institution event in December soon after returning from Paris. “It’s the first universal lasting climate regime that is really applicable to all parties.”

Much remains to be done in implementing the accord to ensure the pledges made by countries are met, and hopefully, exceeded, said Bern Johnson ’87, executive director of the Eugene, Oregon-based Environmental Law Alliance Worldwide.

But Johnson said Stern and his Obama administration colleagues deserve credit for what they have already accomplished.

“The Paris agreement is a huge step in the right direction, and the Obama administration should be applauded for meeting that extremely difficult challenge,” Johnson said. “You always hope they do more, but on balance the Paris agreement looks awfully good.”

Stern left the State Department in the spring, shortly before a United Nations ceremony where dozens of countries signed the climate deal.

He said he’s happy to have more time at home with his wife and three sons after spending three to four months a year on the road.

He’s co-teaching a course on climate negotiations and climate change at Yale Law School this fall and has no plans to join the new administration should Hillary Clinton be elected.

But don’t expect him to stay away altogether.

“He’s got too much skin in the game to sit on the sidelines and not be a player,” Meyer said.