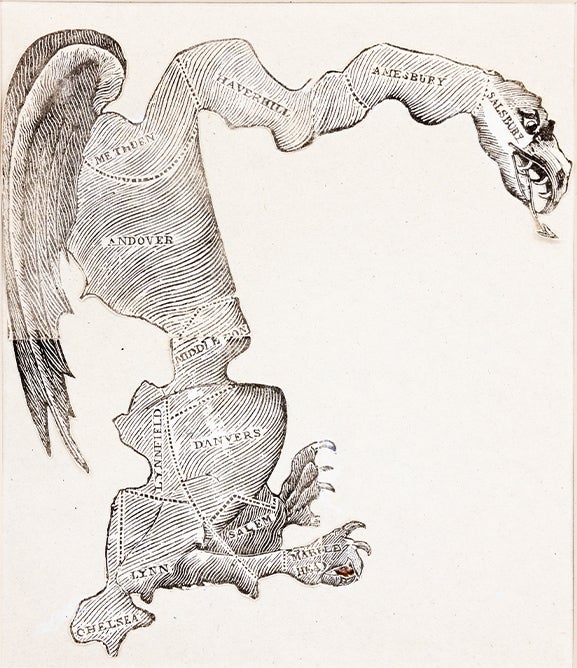

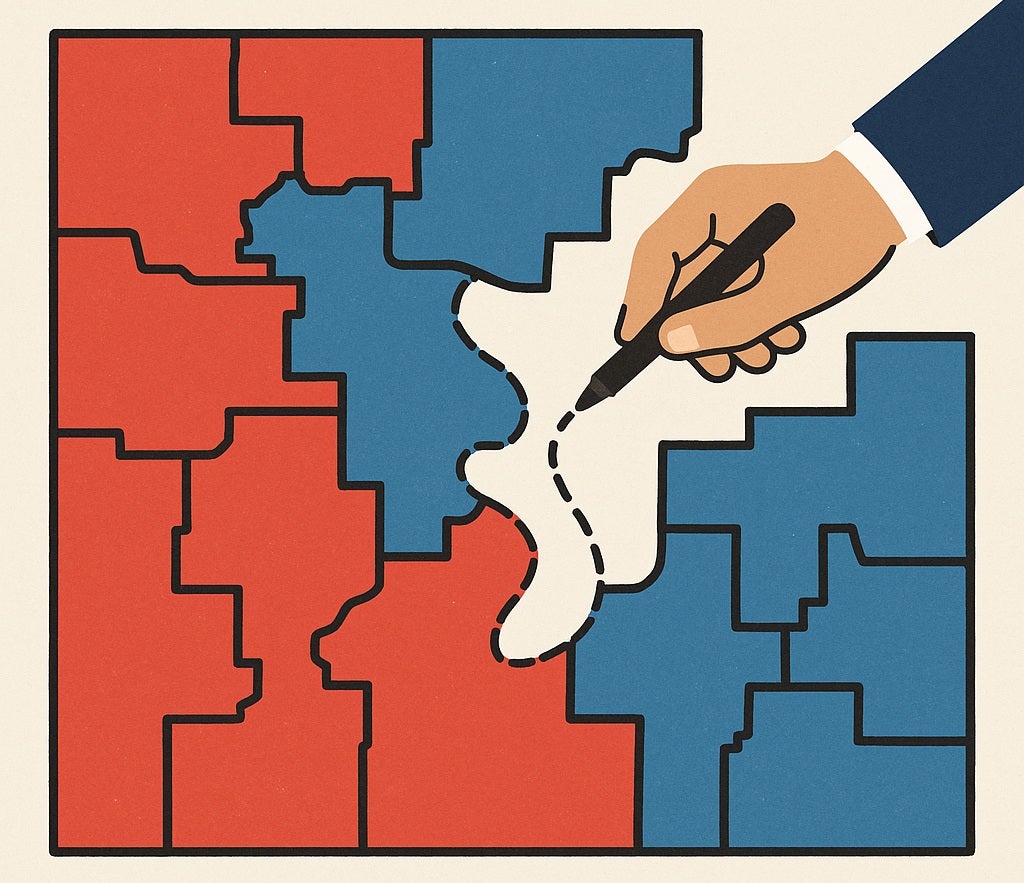

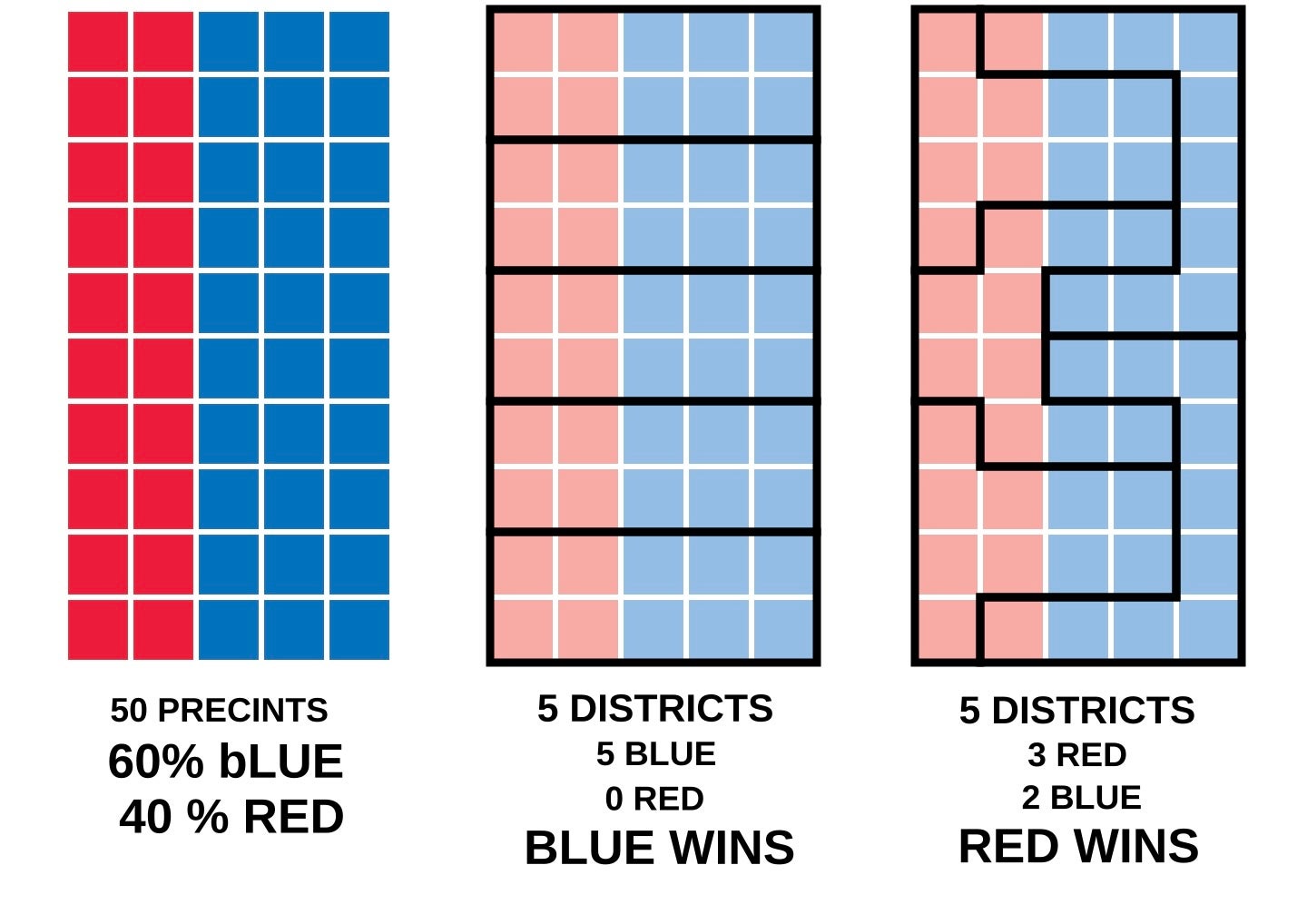

Gerrymandering—the manipulation of electoral district boundaries to gain political advantage—remains one of the most enduring challenges to democratic representation in the United States. Its significance extends beyond partisanship, as district boundaries can shape whether underrepresented communities have an equal opportunity to elect candidates of choice.

Over the past several decades, redistricting law has evolved in two distinct directions. On the constitutional side, the Supreme Court has curtailed federal review of partisan gerrymandering, most notably in Rucho v. Common Cause (2019), which declared such claims nonjusticiable “political questions.” On the statutory side, protections under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 continue to prohibit vote dilution, relying on the three-part Gingles framework to evaluate whether minority voters can elect preferred candidates. These two strands—equal protection and statutory voting rights—form the twin pillars of redistricting doctrine. Yet their interactions often expose a deeper tension: the legal demand for administrable standards meets the growing complexity of empirical methods used to measure fairness.

Experts and scholars have advanced a sophisticated methodological toolkit to evaluate district plans. These techniques—ranging from geometric compactness tests to large-scale computational simulations—now play a central role in how fairness is quantified and argued in litigation in either of the two strands of redistricting cases.

Early approaches relied on geometry. Compactness measures such as Polsby–Popper and Reock scores were premised on the idea that irregular shapes signal manipulation. These metrics remained intuitive and would often be feature in expert reports, but their limitations are well known. Compactness alone does not ensure fairness, particularly in demographically diverse regions where minority communities are geographically dispersed. A district’s shape may appear “bizarre” and still reflect legitimate considerations like preserving communities of interest or complying with the Voting Rights Act. Compactness now thus serves as a contextual indicator rather than conclusive proof of gerrymandering.

Subsequent measures focused on electoral outcomes rather than shapes. Partisan fairness metrics, such as the Efficiency Gap, attempt to quantify how votes translate into seats. By identifying asymmetries favoring one party, these measures provide a more functional test of bias. Yet they are sensitive to turnout, competitiveness, and the number of districts within a plan. Scholars increasingly emphasize that fairness metrics should be interpreted within their jurisdictional context and paired with other indicators, rather than applied mechanically.

The most transformative methodological innovation has been the use of computational ensemble simulations. These approaches generate thousands of legally compliant district maps to establish a neutral baseline. Comparing an enacted plan to this ensemble distribution allows researchers to detect whether its outcomes are extreme outliers—an empirical hallmark of gerrymandering. Their strength lies in transparency, showing what typical maps would look like under neutral criteria. Yet, as scholars caution, ensembles depend on the parameters encoded into the simulation—choices about compactness, county splits, or communities of interest. The neutrality of any ensemble is thus contingent on the assumptions guiding its design.

While ensemble simulations dominate the study of partisan fairness, the analysis of race in redistricting continues to rely on ecological inference. Courts use these statistical methods to assess racially polarized voting—the second and third Gingles preconditions—when direct, individual-level race data are unavailable. Ecological inference allows experts to estimate group voting patterns by combining precinct election results with demographic data, enabling courts to evaluate whether minority voters are politically cohesive and whether majority voters vote as a bloc. The Supreme Court reaffirmed the centrality of this approach in Allen v. Milligan (2023), even as pending litigation in Louisiana v. Callais raises questions about how racial gerrymandering and vote-dilution claims interact under the Equal Protection Clause and Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

Recent innovations have also sought to better distinguish racial predominance from legitimate redistricting considerations. The “envelope method,” first developed in Cooper v. Harris (2017) and refined in Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP (2023), examines whether precincts with higher percentages of Black voters were systematically moved into or out of districts beyond what neutral criteria would require. By identifying whether race, rather than partisanship or geography, drove line-drawing decisions, this approach offers courts a clearer empirical lens through which to evaluate claims of racial gerrymandering.

Beyond the established metrics of compactness, fairness, and racial predominance, emerging work explores how to measure “communities of interest.” These are areas where residents share social, economic, or cultural ties—factors that many state laws require line-drawers to respect. Historically defined through public testimony, communities of interest are now being studied through demographic clustering, textual analysis of public submissions, and survey data. Though still developing, these methods reflect a growing effort to integrate social context into the empirical study of redistricting.

Taken together, these innovations mark a methodological turning point. Redistricting analysis has shifted from evaluating shapes and intuition to testing hypotheses with data. Courts and commissions now draw upon multiple types of evidence—geometric, statistical, and demographic—to assess compliance and fairness. The challenge ahead lies not in inventing new metrics but in ensuring that empirical sophistication remains accessible to the legal system. As the law continues to grapple with what constitutes a “fair map,” the integration of data-driven methods promises a more transparent, rigorous, and accountable redistricting process.

Filed in: In the Community

Contact Us

phone: 617-495-3455

email: asklib@law.harvard.edu

library website: hls.harvard.edu/library

Stay Connected

Library Innovation Lab (LIL) Blog

Instagram @hlslibrary

Facebook @hlslibrary

Et Seq blog (archived)