Eighty years ago, the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg opened just six months after Germany surrendered in World War II. By October of 1946, the judges delivered their sentences, convicting 19 of the Third Reich’s senior leaders. Over the next three years, the U.S. Nuremberg Military Tribunal conducted 12 additional trials, prosecuting Nazi judges, doctors, industrialists, diplomats, and less senior military leaders.

Considered by many to be the most significant series of trials in history, they were established to prosecute those in authority in the Nazi regime for war crimes and crimes against humanity and to create a permanent historical record and precedents for future legal recourse.

Harvard Law School lawyers played roles in the 13 trials. Here are some of the participants.

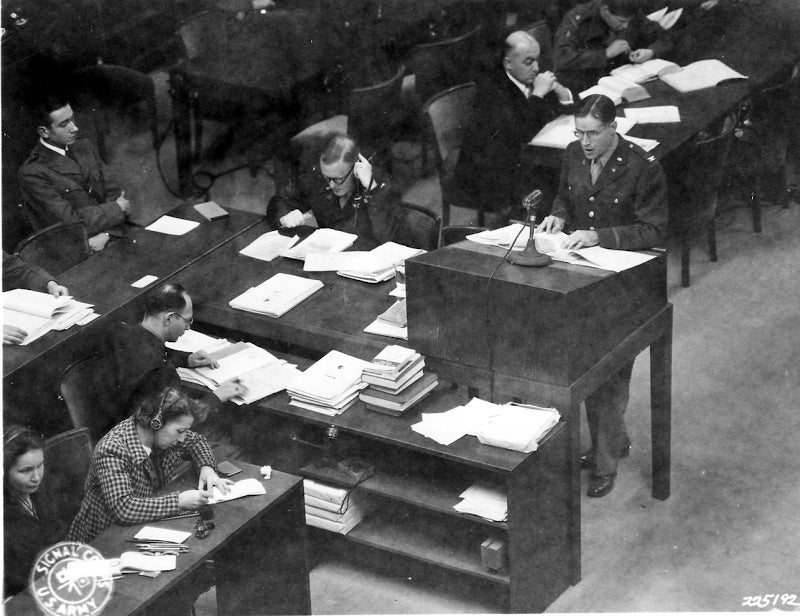

Telford Taylor LL.B. 1932, an Army colonel, was one of the senior deputies to Chief Counsel Robert H. Jackson in the International Military Tribunal in 1945. In 1946, after Jackson left the prosecutor’s post, Taylor, who’d been promoted to brigadier general, succeeded him as chief counsel in the subsequent 12 trials, leading the prosecution and organizing the prosecutorial teams (which may help to explain why so many Harvard alumni participated).

Benjamin Kaplan, who went on to be a longtime professor at Harvard Law School, was a legal strategist for the prosecution for the tribunal.

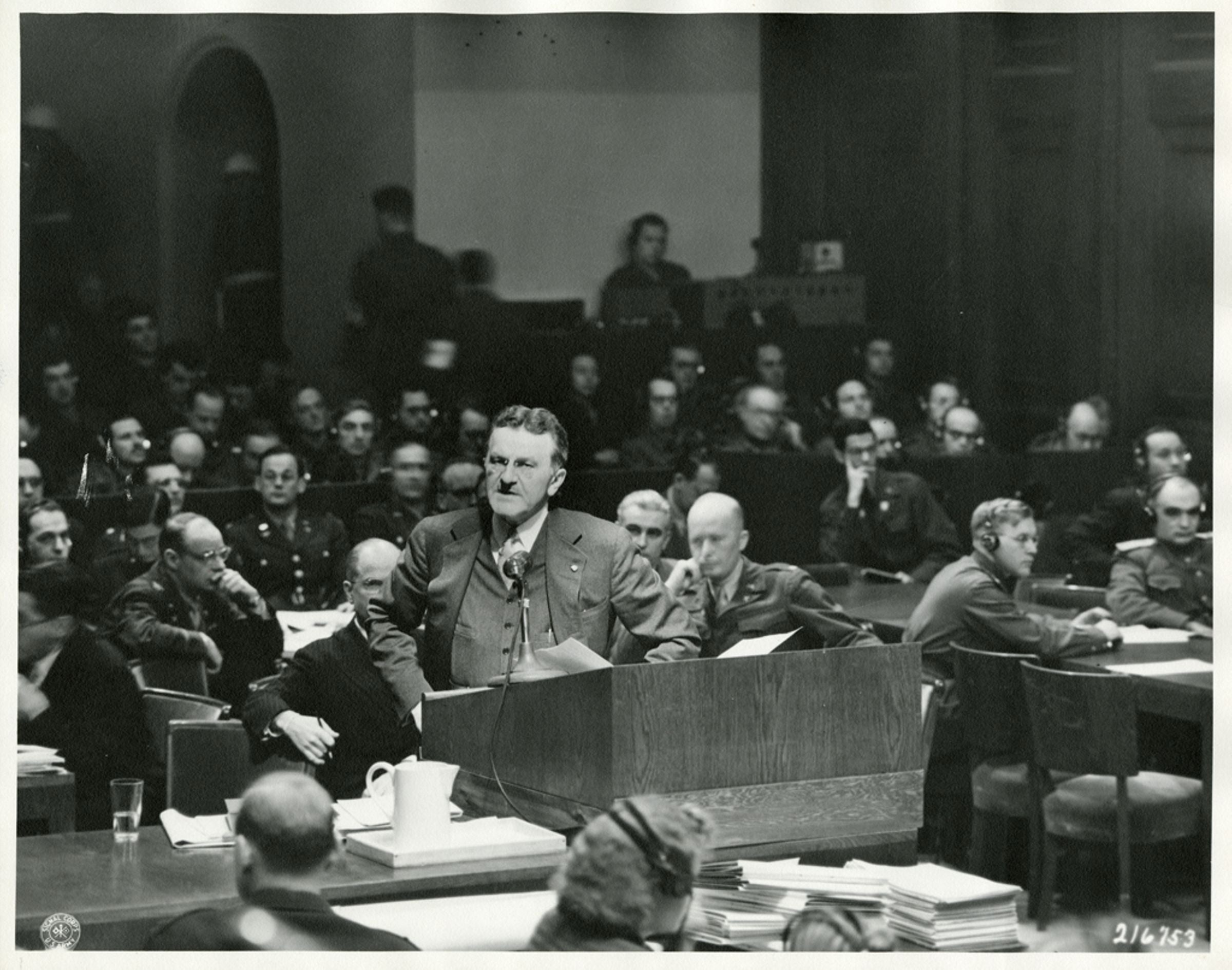

Ralph Albrecht LL.B. 1923 was associate counsel for the tribunal, where his role included gathering evidence against defendants, including Hermann Goering, often referred to as the second most powerful man in Nazi Germany and one of the primary architects of the Nazi police state and the Holocaust.

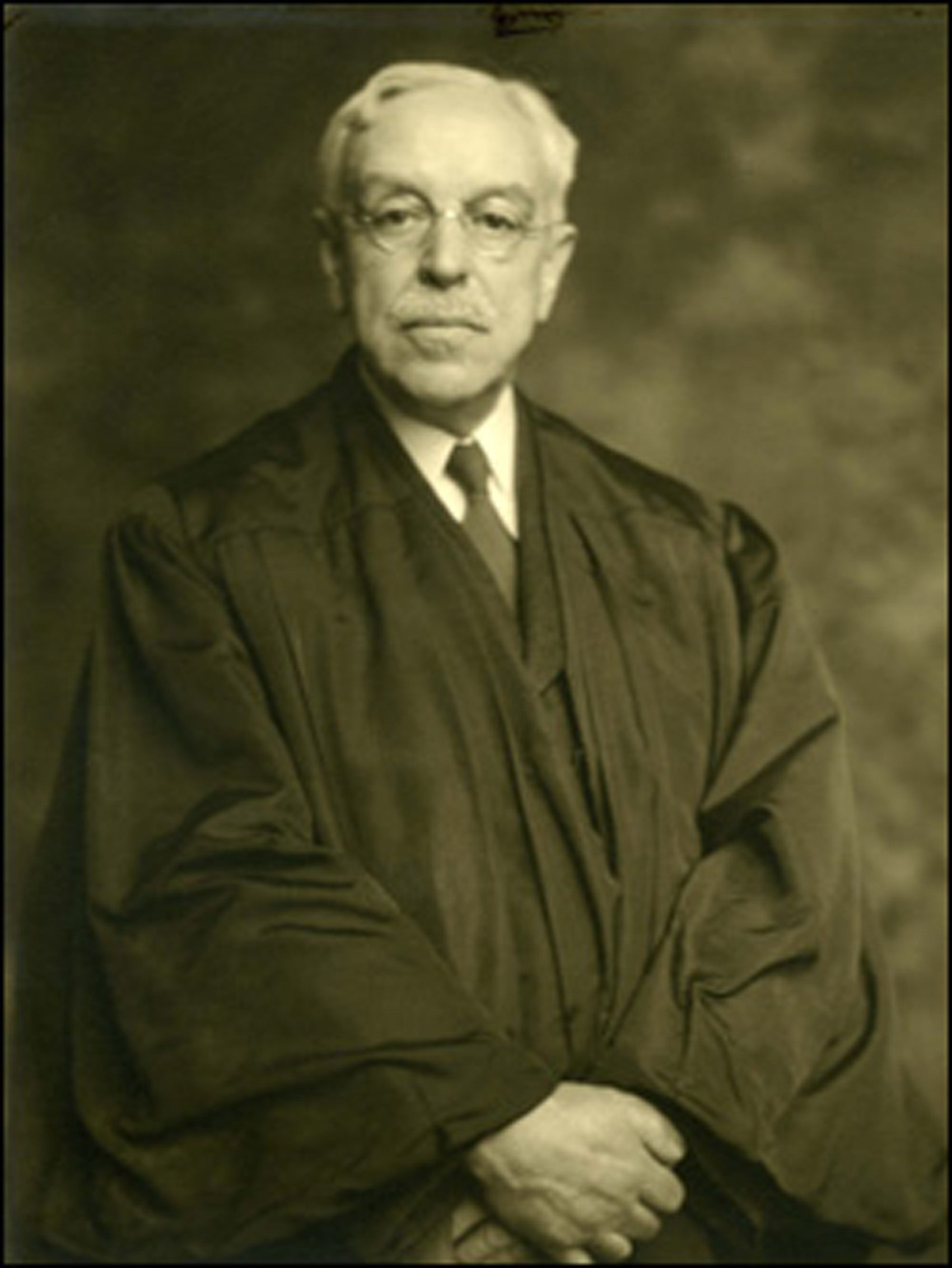

Francis Biddle LL.B. 1911, former U.S. attorney general, was the primary U.S. judge for the tribunal. Each of the four major Allied nations — the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and France — supplied a judge, an alternate judge, and a prosecution team for that trial.

James B. Donovan LL.B. 1940 was an assistant prosecutor at the tribunal. His work included the production of visual evidence of Nazi crimes, among them two films, “The Nazi Plan,” which used captured German newsreel and propaganda footage as evidence against the accused war criminals, and “Nazi Concentration Camps,” which documented the atrocities of the Holocaust. He later worked as a lawyer, a writer, and a diplomat. His book that recounted the role he played in a Cold War prisoner swap was the basis for a 2015 movie “Bridge of Spies” by Steven Spielberg.

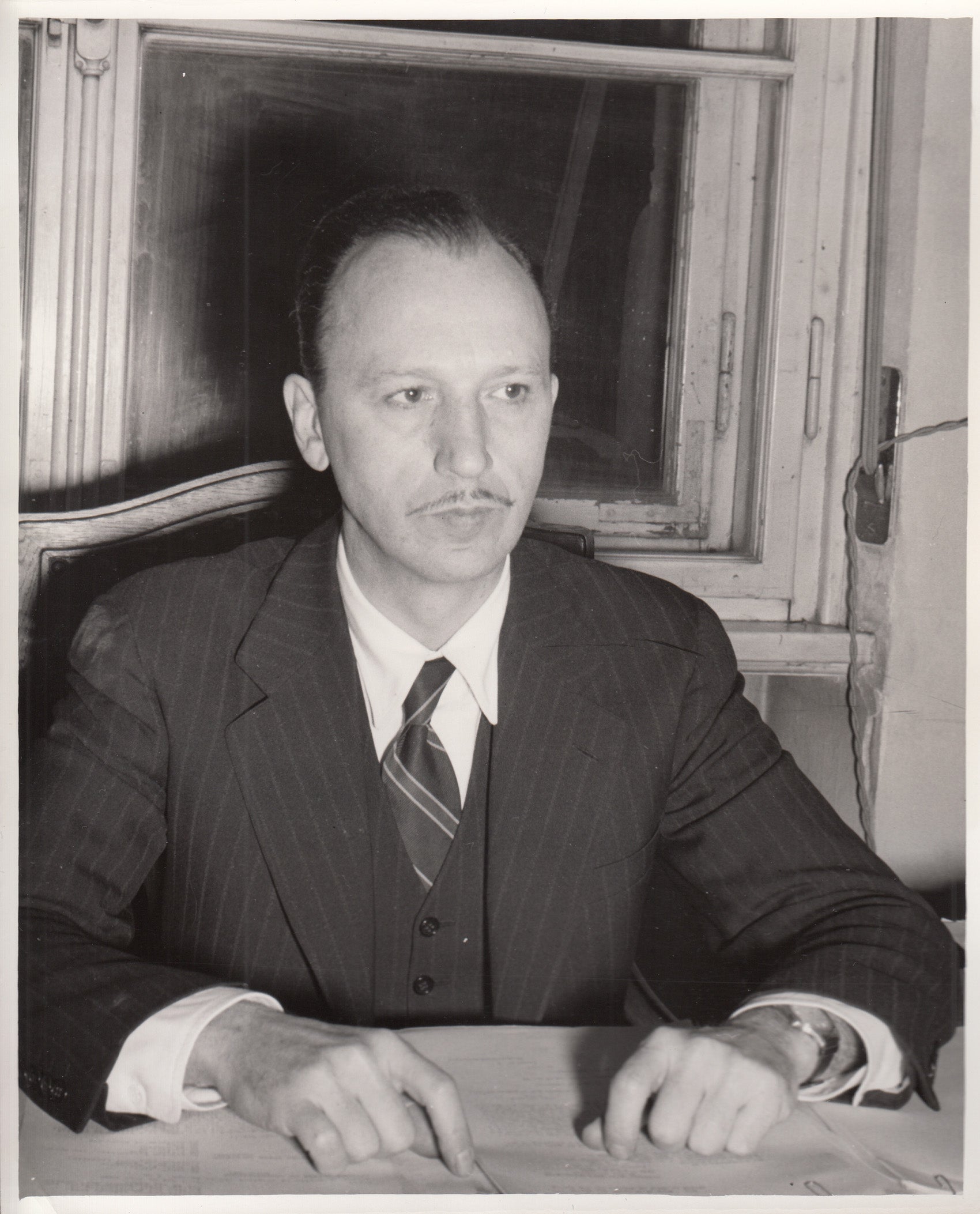

Drexel Spercher LL.B. 1938 was an assistant prosecutor at the tribunal, where he argued cases including one that convicted the head of the Hitler Youth movement and another in which he contended that a deputy to the propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, incited Germans by broadcasting lies on the radio. Spercher stayed on to work on the subsequent trials and at different times led four divisions of the American prosecution team and was a top deputy to Taylor.

Leonard Wheeler Jr. LL.B. 1925 was an assistant trial counsel to the tribunal and was responsible for reports used in the trial, including “Suppression of the Christian Churches in Germany and in the Occupied Territories.”

Raymond J. McMahon, Jr. LL.B. 1945 was a prosector in the second trial, of Field Marshal Erhard Milch, who was chiefly responsible for aircraft production during the war, and was found guilty on charges related to slave labor.

William Irving Hart LL.B. 1929 was a prosecutor on the fourth trial, of SS officers charged for their administration and involvement in Nazi concentration camps.

Charles Brown Sears LL.B. 1896 was presiding judge in the fifth trial, against a group of industrialists charged with crimes including slave labor.

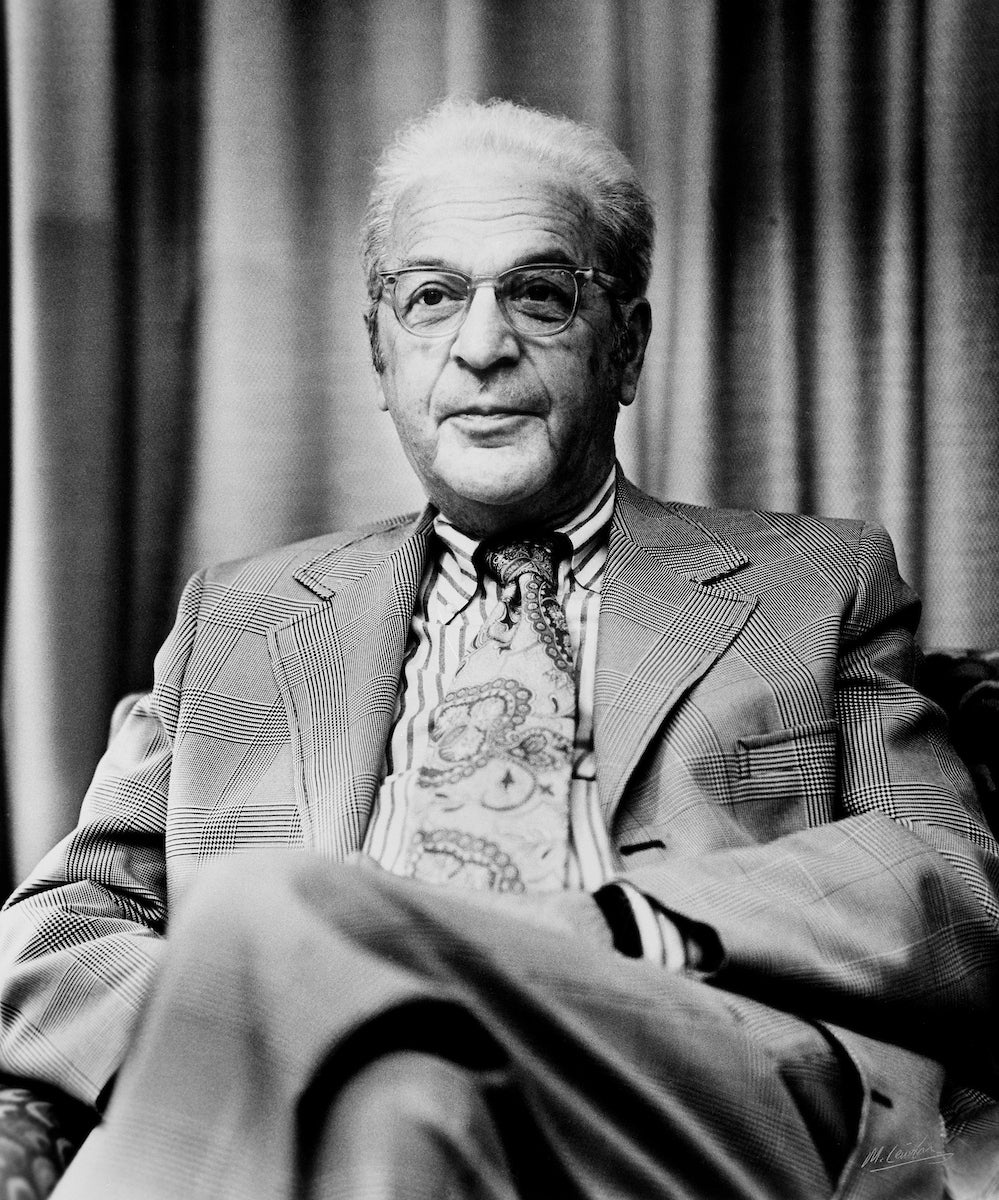

Benjamin Ferencz LL.B. 1943 was chief prosecutor of the ninth trial, known as the Einsatzgruppen case. In his opening statement he said, “It is with sorrow and with hope that we here disclose the deliberate slaughter of more than a million innocent and defenseless men, women, and children.” He brought the case against 22 Nazis, including six generals, who organized, directed and often joined roaming SS extermination squads. He was 27 years old. He was also a special counsel in prosecuting the 10th trial, the Krupp case, another proceeding against German industrialists. Ferencz later was a law teacher, writer, and lecturer, advocating for world peace and the establishment of a permanent international criminal tribunal to ensure enforcement of international law.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.