Misinformation and disinformation about COVID and government-led health measures to combat the pandemic hampered efforts to form a unified national response to the disease. Public health officials, who struggled to convince doubters and skeptics, are still working through how and why it happened.

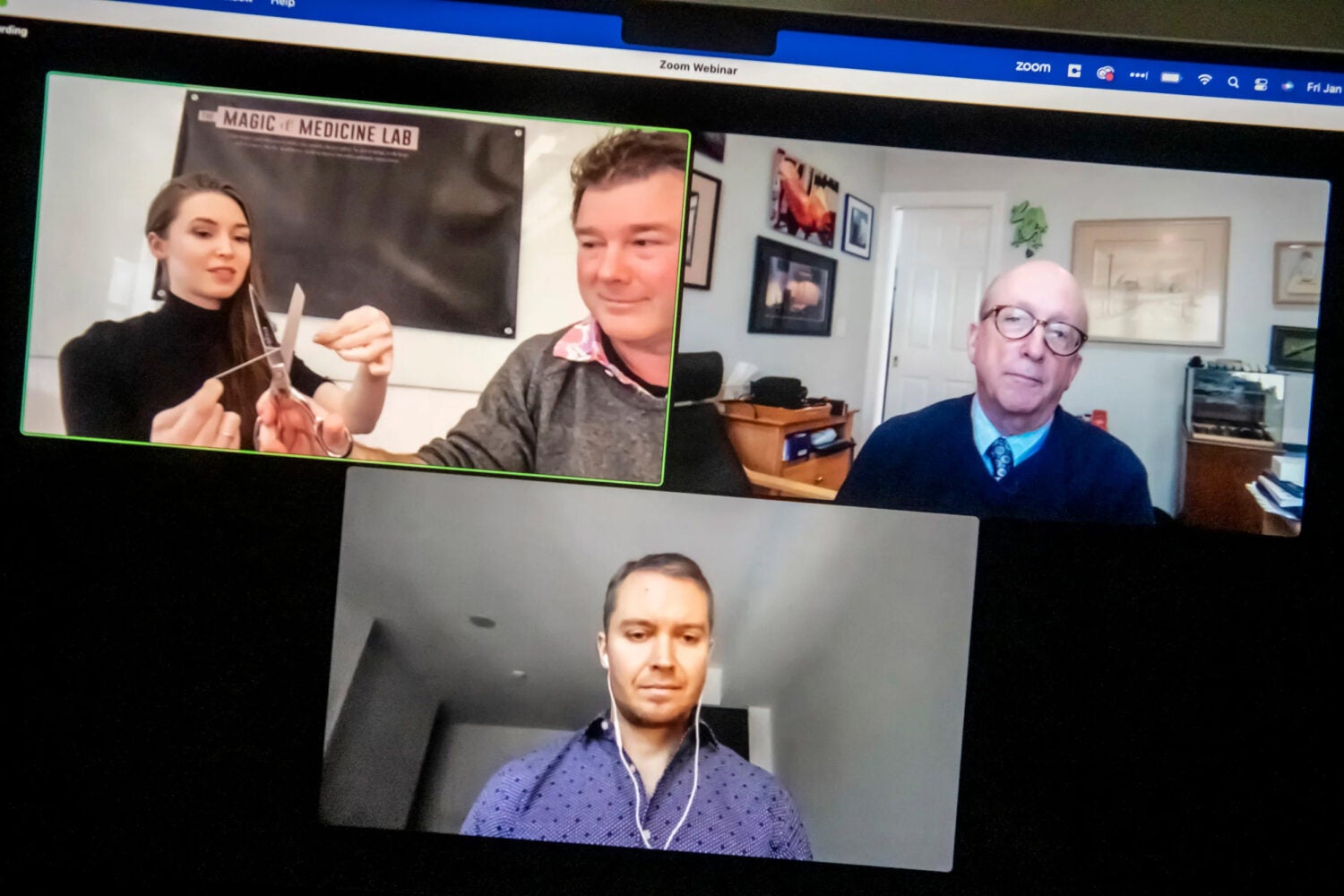

Panelists at a talk hosted by the Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law, Biotechnology, and Bioethics at Harvard Law School last Friday examined surprising parallels between magic and misinformation, a discussion that offered insights into some of the cognitive forces at play.

Magic, misinformation, and disinformation are effective, the experts said, because they take advantage of how the brain processes information. Misinformation, sharing inaccurate information unintentionally, and disinformation, spreading falsehoods to mislead, each contain factual or logical holes that our brains rush to fill much the way it does when we watch magic tricks, said Jeanette Andrews, a magician and artist alum of the MetaLAB (at) Harvard.

“We’re a lot of times either skimming information and trying to fill in those mental gaps, whether consciously or unconsciously. As a species, we are always craving certainty, so we’re always on the hunt to be able to complete a picture, to complete information,” she said.

Creating conceptual gaps typically involves either giving audiences incomplete information or too much of it all at once, what some disinformation purveyors call “flooding the zone.”

“Magic performances are very carefully constructed to either overwhelm the viewer with too much information, so you have to pick out what seems like only the most important pieces of information, or maybe not quite enough information, so then you are making mental leaps based on the perceptual information that you have to create a complete experience,” said Andrews, as she performed a magic trick in which a piece of string cut in four places appears to reattach itself.

The audience knows intellectually that a solid piece of string cannot put itself back together after being cut into pieces, and yet, the brain is telling them that is what they have witnessed.

“That’s where a lot of times our cognitive biases jump in, to start to fill in those gaps,” she added. “So, if you see something, or even part of something, that is presented to you to be true, you’re more likely to continue on in that frame of belief.”

Jay Olson, a behavioral science fellow for the government of Canada who has studied placebo and nocebo effects, said that because the public learns about such products from the sites, friends, and other sources they trust, it almost doesn’t matter whether the products actually do what the hawkers claim they do because research shows the placebo effect from the disinformation about them is so powerful.

“The oil itself may not have any effect on anxiety … if they believe that this can reduce their anxiety, then sometimes the oil … can end up reducing the anxiety that they feel,” Olson said. Research shows some people do experience physical results, but the change comes not from the products, but from expectations that they really do work.

As the pandemic demonstrated, the rampant spread of misinformation and disinformation about public health often has dire, real-world consequences. Recommendations from scientists and government health agencies about COVID treatments and safety precautions were frequently questioned or contradicted by non-medical professionals, leading some to get sick and avoid the care they needed, and some health care providers to face violent threats from the misinformed.

Messages that sowed doubt about the reliability of federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data and discredited Anthony Fauci, former director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, or promoted unproven home remedies over tested vaccines, were boosted by the cognitive reality that people are more likely to unquestioningly accept claims without evidence if they align with their preconceived expectations.

Countering this reality has been particularly difficult in public health because of the very nature of science, where knowledge is tested and challenged and changes as new information and new interpretations come to light, said Ross McKinney Jr., chief scientific officer and senior medical scientist at the Association of American Medical Colleges.

“A critical role of science is to constantly explore, to challenge existing hypotheses, to synthesize and create new facts, and what we knew in the past is not necessarily what we understand the truth to be now. That is a normal part of science — it is constantly evolving,” said McKinney.

But that uncertainty and evolution in scientific inquiry can come across to nonscientists as inaccuracy and unreliability, leaving a dangerous void that disinformation and misinformation will fill. During the pandemic, critics accused public health officials of misleading the public when new evidence about the novel coronavirus triggered revised protocols for prevention and treatment. And because the public is so dependent on others to explain new scientific data and research, it’s critical that they look to and trust public health experts, he said.

“We need people like the [National Institutes of Health] to be believed, we need them to be reliable. They should give the basis of the information, as well as an interpretation. Whoever is providing information should be consistent and if there’s an inconsistency, explain why,” said McKinney.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.