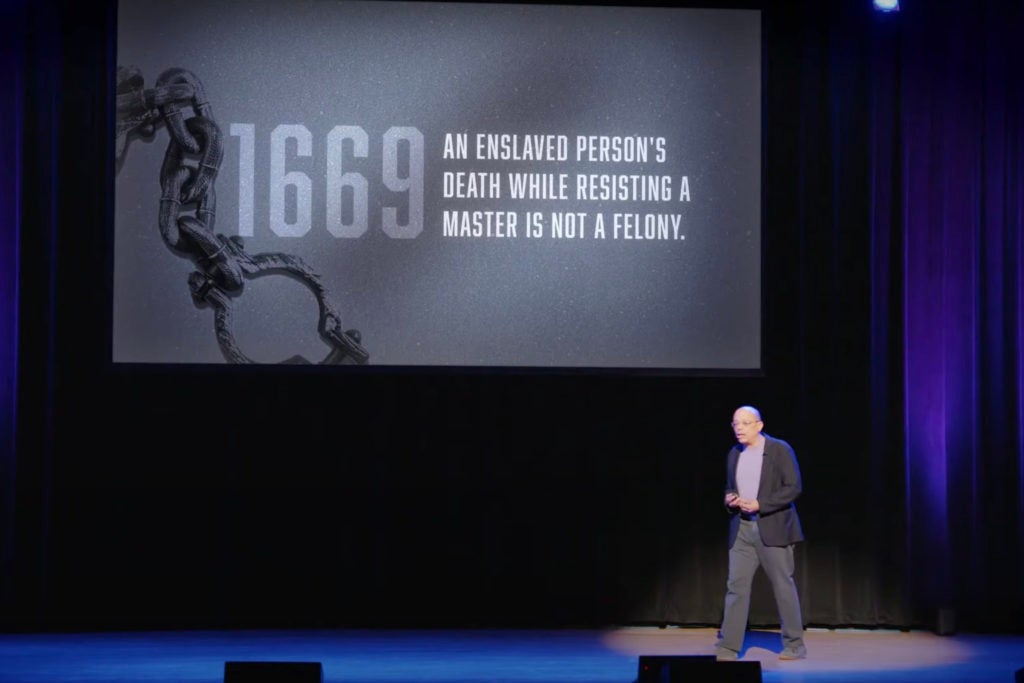

There’s a scene in the new documentary film, “Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America,” where Jeffery Robinson ’81 engages with a white man in Charleston, South Carolina who is holding a Confederate flag. The man insists the Civil War wasn’t about slavery. Robinson, who was a criminal defense attorney in Seattle for 34 years, is well-practiced in dismantling that argument with the historical truth based on original source documentation including the Constitution and the secession declarations of the Confederate states.

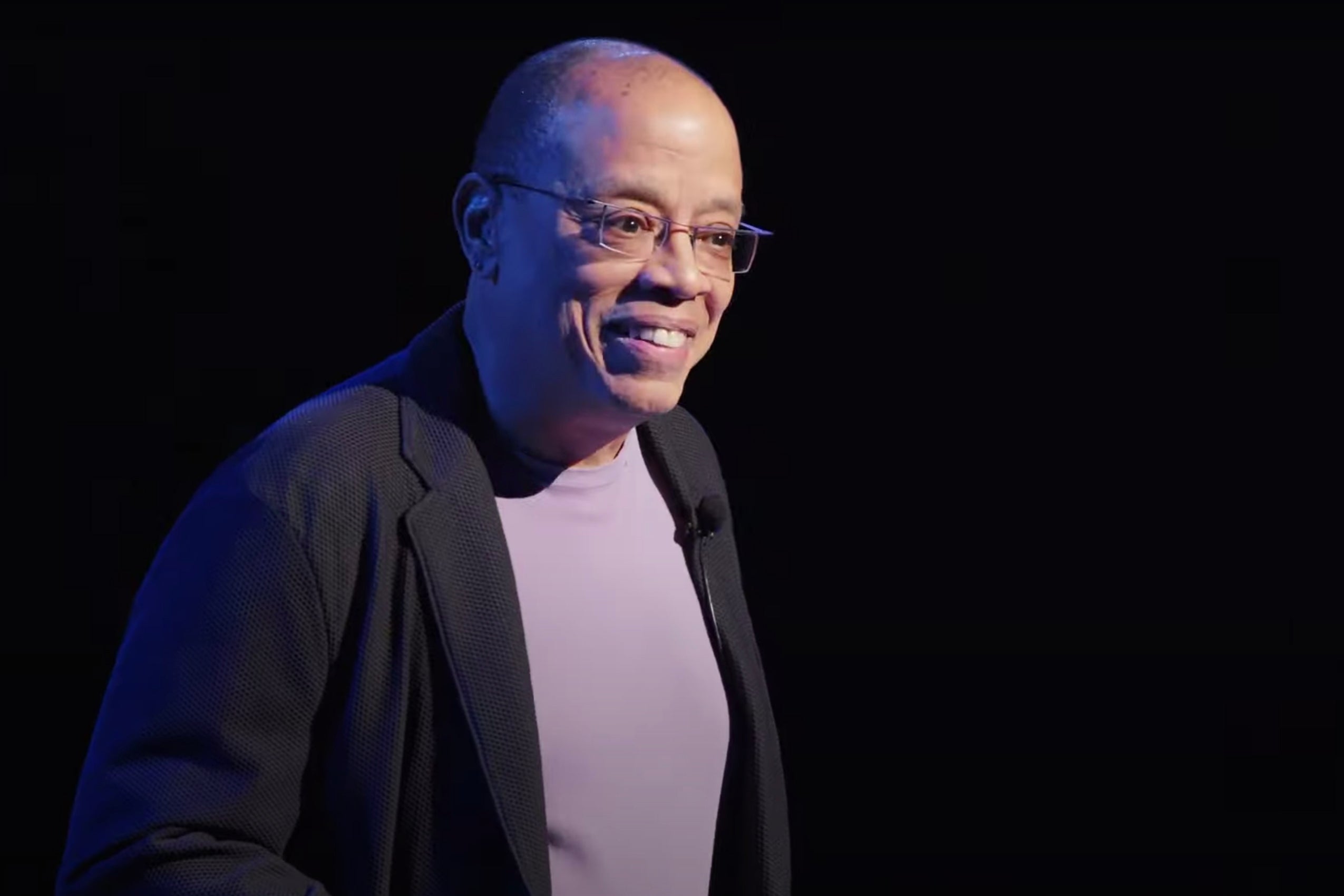

“I’m constantly telling folks, ‘Don’t take my opinion on anything. But if you want to know what the Constitution said about Black people, you can go read it. You do that, and then let’s have a conversation,’” says Robinson, a former ACLU deputy legal director, who since 2012 has traveled the country presenting a groundbreaking lecture that challenges widespread but historically false narratives about racism. After hearing the presentation in 2017, filmmakers Emily and Sarah Kunstler approached Robinson about creating the documentary, which features his lecture along with archival footage and interviews with Americans around the country. Already in release in more than 300 theaters nationwide, “Who We Are” is garnering rave reviews and widespread coverage by major media outlets, and will also have a streaming release.

The film is only the first step for the Who We Are Project, a not-for-profit organization whose purpose is to have a “significant role in correcting the narrative of our history of anti-Black racism over the next five years,” Robinson explains. Today, as at other points over the past 400 years, the nation is at a tipping point in addressing discrimination, he believes. “The discussions that we’re having about where America should go in the future have to be informed by the truth about what brought us to the present,” he says. “George Orwell said it most ominously when he said, ‘Who controls the past controls the future.’”

America has never looked this truth squarely in the face, he adds. “We have not made policy with this history in mind. We have not looked at the criminal legal system with this history in mind. We have not looked at the medical industry with this history. What would happen if we did? One in five Black Americans live in poverty today; what would happen if it was one in fifteen? And I don’t mean for Black America, I mean for white America,” he says. Communities would be stronger, safer, and healthier, he argues, adding, “Everybody benefits and profits from this.”

Robinson, who grew up in Memphis, went to Harvard Law School to become a criminal defense attorney. After more than three decades in that work, he joined the ACLU in 2015, leaving in 2021 to focus fulltime on the Who We Are Project. About a decade earlier, his teenage nephew’s mother died and the young man came to live with Robinson and his wife. Robinson wanted to help him navigate being a Black man in America and was surprised to learn how little he himself knew about the history of race in the U.S., despite having studied at Marquette and Harvard Law School. He decided to share what he learned in order to correct the prevailing narrative and soon found himself lecturing nationwide.

“Racism is more than prejudice, it’s prejudice plus social power plus the legal authority to take your prejudice and infuse it in the social structures of the country,” he says. “The equation of racism with prejudice is a method of distancing oneself from having to take responsibility for what’s happening now,” because someone who is convinced they aren’t prejudiced may feel no responsibility to address ongoing inequities.

Take the issue of voting. After the Civil War, there were 700,000 Black registered voters “because our community [was] ready to start participating,” he says. But once Southern states passed literacy codes and other voter suppression laws, the number of Black voters plummeted. Louisiana alone went from 130,000 registered Black voters in 1896 to about 5,000 just two years later, he says.

This disenfranchisement campaign continued with the disproportionate incarceration of Black people and laws stripping felons of the right to vote. Although The Voting Rights Act of 1965 prohibited racial discrimination in voting, “now the Supreme Court under John Roberts is saying, ‘We don’t need those protections anymore because there is no racism anymore,’” Robinson says. “As soon as the Supreme Court made that decision, thirteen states in the South immediately started passing restrictive voting laws. So, when you say all these voting laws today have nothing to do with race, nothing to do with marginalizing the Black folk, you are ignoring this history completely.”

The truth is also under attack via new laws that curtail how history can be taught in public schools, says Robinson, who urges lawyers to challenge these statutes. “The one thing that is necessary for a democratic republic to survive is an educated populace,” he says. The Who We Are Project will be engaged in this area not by filing lawsuits — that’s the job of practicing lawyers, he says — but through education. It will be inviting parent organizations, student organizations, teachers, community organizations, religious groups, political groups, and others to view the film and hold discussion groups. He believes that once people “get just a tiny peek at the truth, you won’t be able to stop.”

The Who We Are Project is fundraising to launch a virtual museum and library they envision as a gathering place of historical narratives and original source documents. “If the information is out there and people get it — whether conservative or liberal or Democrat or Republican — I think they will be moved by the truth,” Robinson says. “If you’re wondering, ‘What did the states that left the union think, why did they leave, was it about slavery or something else?’ — you don’t have to wonder, you don’t have to listen to a politician or an advocate from today to put a spin on it. Just go read what they said. They were crystal clear about what they were doing. And I promise you, by the end of what you’re reading, there won’t be a debate anymore.”

“If we start teaching the truth about those facts, we will look at the problems that exist today. And the solutions that we come up with, by definition, will be different because they will be informed by a history that we have never considered,” he says.

On the contentious issue of reparations for Black people, for example, Robinson points out that unbeknownst to most people, there is precedent. “We have paid reparations for slavery — we paid it to owners of enslaved people,” he says. In 1862, the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act became law, and $1 million was paid to Washington, D.C. owners of enslaved people who were freed.

“So, let’s have the conversation about whether reparations [to Black Americans] are appropriate,” says Robinson. Legislation in the U.S. House of Represenatives, H.R. 40, seeks to establish a commission to study and develop proposals for reparations to Black Americans and make recommendations to Congress. “Who could be against that? And if the truth about the history says there should be no reparations, then people need to live with that. But let’s focus it on the truth about the history.”

“This film isn’t for white people, it isn’t for Black people,” he says. “This film is for everyone in our country because this history was stolen from all of us. And it is not on just Black people to reckon with and regain this history. It’s on all of us.”