The rights of American citizens to freely express their personal views have historically enjoyed thorough protection under the First Amendment. As United States Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall famously said, “To protest against injustice is the foundation of all our American democracy.”

But harm can result when large groups of people convene to exercise their core civil liberties. At “Politics, Torts, and the First Amendment: The Limits of Protest and Public Pressure Torts,” a First Amendment scholar and tort law expert examined the limits of liability when speech causes harm.

Hosted by the Harvard Law Federalist Society, the Oct. 22 discussion featured remarks from Professor Eugene Volokh, the Thomas M. Siebel Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford and Gary T. Schwartz Distinguished Professor of Law Emeritus and Distinguished Research Professor at UCLA School of Law, and John Goldberg, the Morgan and Helen Chu Dean and Professor of Law at Harvard Law School.

Volokh led off the event by describing how protests and public pressure campaigns may amount to the commission of a tort: that is, a legal wrong that gives victims the ability to sue wrongdoers in civil court.

He noted, for example, that lawsuits in the context of protest often involve claims of trespass, nuisance, and defamation. He also mentioned less frequently cited tort claims that might in theory apply to certain activities connected with protests and public pressure, including false imprisonment.

“Let’s say a protest essentially traps people so that there is no exit,” posited Volokh. “They’re stuck even for a matter of a few hours, indefinitely, on a bridge and can’t leave. They can’t leave because you’re not allowed to turn around and you can’t just get out of your car, [and] it’s illegal to leave your car on the bridge. That could arguably constitute false imprisonment.”

He emphasized that, although protests and public pressure campaigns often stem from passionate opinions on political issues, the use of tort law to hold protesters to account has not historically been linked to any particular political affiliation.

“It applies to such a wide range of groups across the political spectrum because there are a wide range of political groups that engage in behavior that, at least some of which, may be tortious,” said Volokh.

Volokh concluded by sharing his observations on an emerging phenomenon involving the scope of liability in protest and public pressure cases. According to him, entities that support protests where participants cause actionable harm to others have increasingly faced “complicity” lawsuits aimed at holding them responsible for the participants’ wrongful acts.

“If you can hold protest or pressure campaign members liable, you might be able to hold backers liable on an aiding and abetting theory if they acted knowingly,” Volokh said. “Let’s say somebody donates money to some organization knowing that they engage in protests that block highways, possibly tortiously — that could constitute aiding and abetting.”

“Let’s say a protest essentially traps people so that there is no exit … That could arguably constitute false imprisonment.”

Eugene Volokh

Unlike tort claims brought against individual protesters, complicity lawsuits against entities have recently demonstrated the potential to result in steep financial consequences. In particular, Volokh referenced the outcomes of Energy Transfer LP v. Greenpeace International and Gibson’s Bakery v. Oberlin College, where juries respectively found against entities deemed to have facilitated protests and imposed significant damage awards.

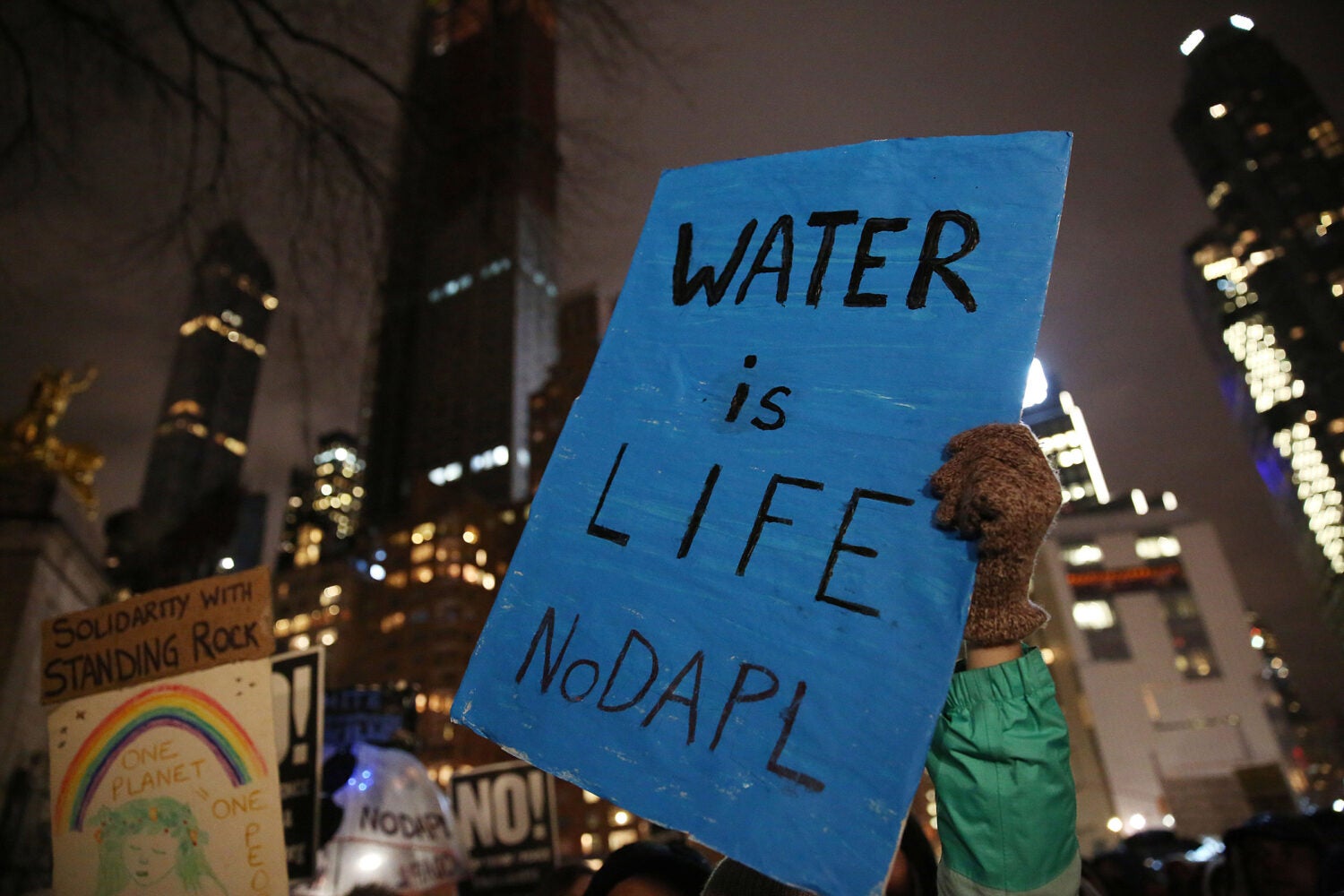

“On the complicity point, I want to give you two numbers: a $660 million verdict against Greenpeace for organizing the Standing Rock protests against the [Dakota Access] Pipeline and a $36 million payout by Oberlin College for supporting, in very minor way, student protests found to be defamatory,” he said.

Volokh then introduced Goldberg, who began his remarks by addressing the value of tort law and its importance to maintaining a free and peaceful society.

“If you care deeply about some of our most salient legal values, political values, and traditions — including things like individual liberty and individual responsibility — you should like tort law,” remarked Goldberg. “A lot of what tort law is about is identifying the conditions and terms under which each of us … is responsible to ensure we do right by our fellow citizens, we do not injure them, and we do not interfere with their lives in various ways.”

Whereas Volokh provided a general overview of protest and public pressure tort claims, Goldberg focused specifically on the concept of complicity. He began by identifying the idea of “negligent enabling,” which some scholars have argued provides the basis for a broad ambit of civil liability that could, in principle, apply to organizers of political protests that result in personal injuries.

Goldberg expressed some skepticism about the legal validity of this approach: “I think that’s far too broad a description of the state of the law. I don’t think there is a tort called negligent enabling,” said Goldberg. “I think there are instances of negligent enabling, but they’re very carefully circumscribed.” He added that a general principle of negligent enabling would cast a very wide net of liability.

“If you care deeply about some of our most salient legal values, political values, and traditions — including things like individual liberty and individual responsibility — you should like tort law.”

John Goldberg

Goldberg also explored other tort principles that could potentially justify holding supporters civilly responsible for wrongs committed by participants, including “aiding and abetting.” Although the concept of aiding and abetting liability arises much more frequently in the context of criminal law, he pointed out that it exists in civil law as well. According to Goldberg, though, its definition and limits in the context of civil law remain significantly underdeveloped. He encouraged students in the audience who are interested in the topic to research and help clarify the law in this area.

Goldberg concluded with thoughts on whether torts such as interference with contract might be available to persons who lose their jobs because of public pressure campaigns, noting that such claims are not likely to succeed unless courts loosen traditional liability limitations that aim to ensure broad legal leeway for fair economic competition.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.