Seventy years after the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, which imposed new limits on presidential power, what guidance does it provide to commanders in chief and their legal teams today? According to a panel of experts at Harvard Law School last week, the answer is: not much.

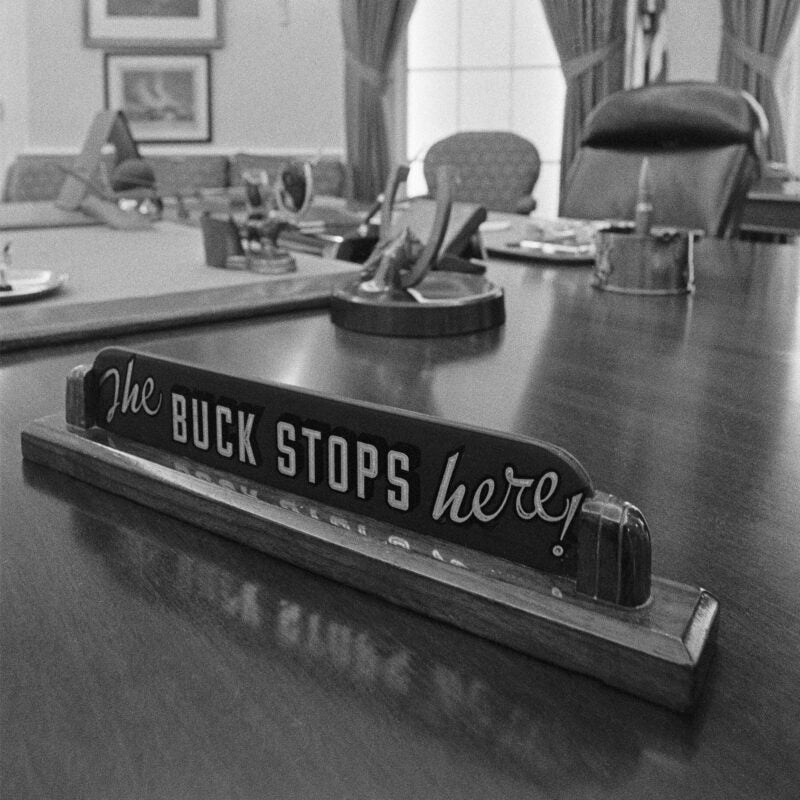

Youngstown was decided during the Korean War after President Harry Truman attempted to take control of steel production facilities, which were on strike when war materials were needed. As Harvard Law School Professor and panel moderator Jack Goldsmith said, the Supreme Court issued a “short, straightforward, formalist opinion” which invoked previous labor disputes and ultimately denied Truman the authority to seize the mills. Yet Goldsmith, who served assistant attorney general before coming to Harvard, said that the implications for future cases were less clear.

The decision, he said, is remembered largely for Justice Robert Jackson’s concurring opinion, which outlined three levels of presidential authority. Category one would be the president acting in accordance with powers granted by Congress. Category three would be the President acting unilaterally. “But Jackson didn’t say that this couldn’t happen; he only said it represents the ‘lowest ebb’,” Goldsmith pointed out. The more mysterious middle ground, where more cases would likely fall, was described by Jackson as a “zone of twilight.” As Goldsmith said, “I’m not sure what that means, and I’ve been teaching it for 30 years.”

Panelists Neil Eggleston and Steven Engel agreed thatYoungstown is more useful from a theoretical than a practical standpoint. Eggleston, a lecturer on law who served as White House counsel to President Barack Obama, said that “Youngstown remains an important analytical structure, but I’m not sure it goes further than that. Category three is useful as an identifier, though it actually comes up quite rarely. The most interesting cases come up in category two, but the interesting thing is that it gives you almost nothing to decide cases. I almost wonder how much Jackson was just describing something and not even coming up with a way to formulate.”

Engel, who headed the Office of Legal Counsel under Trump, concurred that he hadn’t had much occasion to put Youngstown into practical use. “It’s emerged as a case that is routinely cited, but it’s a bit unclear what value it adds when it comes to the analysis.” The main takeaway, he said, is that “presidential powers are not fixed; they vary according to circumstance.”

Eggleston and Engel talked about moments in their respective administrations where the use of presidential powers fell into the “twilight zone.” Eggleston recalled the complicated matter of Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl, who was captured by the Taliban in 2009 and held captive for five years. Informed that Bergdahl’s health was failing, Obama negotiated a controversial agreement to release five Taliban prisoners in Guantanamo Bay in exchange for Bergdahl; bypassing a statute that nobody was allowed to be released from Guantanamo without thirty days’ notice. This prompted tension between the president and Congress, particularly when evidence emerged after Bergdahl’s release that he may have been a deserter. “Congress went bats, but they couldn’t go totally bats because we freed an American serviceman. We trumpeted what a great guy he was and as it turns out, he wasn’t one. So we violated a statute within my first couple weeks.” Added Engel, “Not violated — you ignored a statute that was unconstitutional.”

Engel discussed Trump’s attempts to build his border wall. Because Congress would not grant the $5.7 billion that he requested, the president attempted to seize privately held lands via eminent domain. This proved a mixed success, Engel admitted. “Congress chose not to fund it to the extent Trump wanted; but they passed other statutes that allowed him to move money around. We litigated and relitigated, won some and lost some. But we were never going to have any definitive ruling. It really shows how narrow and unsatisfying this ‘zone of twilight’ is.”

Even without Youngstown, the panelists said, the limits of presidential power have fluctuated in different circumstances. Engel cited Abraham Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus during the Civil War, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s seizure of a Montgomery Ward department store during a labor dispute that threatened production for World War II.

“I don’t think either of these would be considered … constitutional today.” Eggleston said he’d hoped for Congress to address the president’s ability to impost emergency orders — a power that was used extensively under Trump, and seems to be continuing under President Joe Biden. “I was hoping that Congress would take a look at emergency orders. But with student loans and COVID emergency, Biden hasn’t made it all that easy.”

Given the mixed feelings about Youngstown, one student noted that the three-part test was “artful but not useful,” and asked why the panel was discussing it at all. Engel said that the decision makes one clear point: “The Court decided that there are no inherent emergency powers, especially when it comes to property rights of citizens. The Court has applied the Youngstown framework to some of these cases, and it is a landmark case. It’s often cited even though it may not be that helpful.”

Added Goldsmith, “It’s an excellent opinion for organizing thoughts, if not for answering questions. Even if it’s not determinate, it’s very helpful for setting up analysis. Plus, the whole opinion is full of insights and well worth studying deeply.”