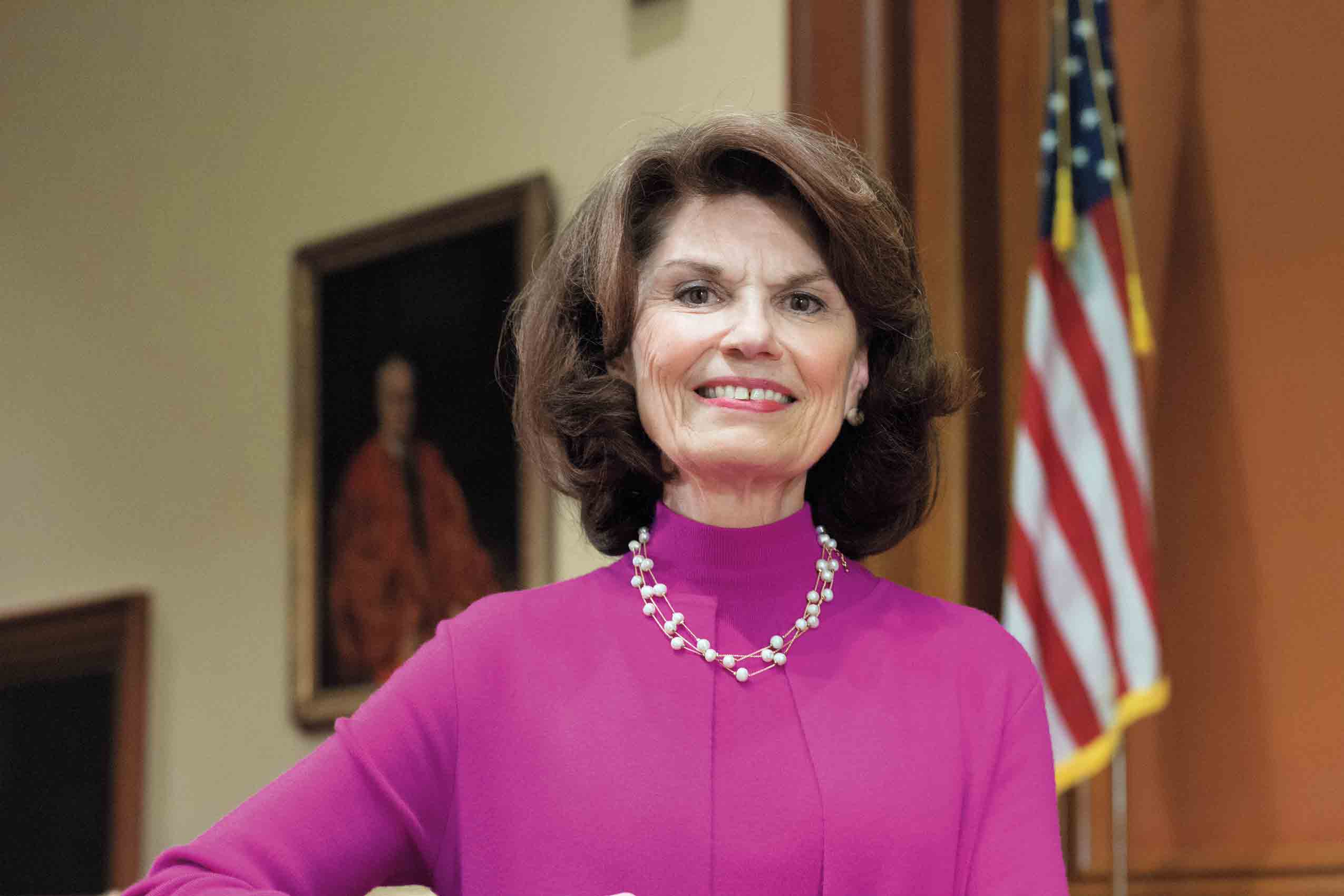

When Reena Raggi graduated from Harvard Law School in 1976, the student body was only 20 percent female. But Raggi, who went on to serve 30 years on the federal bench—on the District Court for the Eastern District of New York from 1987 to 2002 and since then on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit—never thought of herself as a Harvard pioneer.

“I think we knew that the generations before us had faced more significant challenges,” said Raggi, who graduated from Wellesley College before entering HLS. “Perhaps having come from a women’s school, I had become used to women running everything. We were the first class to be housed in what were then called the new dorms, and that was more a new experience for the male students—they weren’t used to having women among them. But I never encountered anything in the classroom that made me feel we were being treated differently than men,” said Raggi, who returned to HLS in March to judge the Ames Semi-Finals. While she was on campus, she also participated in a Q&A with Dean Martha Minow.

Raggi said her post-Harvard career path “wasn’t that untraditional.” After clerking in the 7th Circuit for two years, she moved from private practice to prosecution. Yet it did involve a number of firsts: She was the first woman to head both the Eastern District of New York’s narcotics unit and its corruption unit, and later the first woman named U.S. attorney in any of the four federal prosecutors’ offices in New York. “Narcotics is quick responses, middle-of-the-night phone calls,” she said. “You have agents who want to know if they can go right in or need a warrant, and you need to prepare in advance so you can answer questions on the fly. Public corruption is more steady investigation, putting the pieces of the puzzle together. You didn’t want to go to trial unless you were sure you could hit the bull’s-eye; you didn’t want to be in the papers every day if you couldn’t.”

Just 10 years out of HLS, Raggi was nominated by President Reagan to serve as a district judge in the Eastern District of New York. On that court, she tried cases that made headlines—and in one case, sent shock waves through New York. United States v. Schwarz was a civil rights case related to the physical and sexual assault of Haitian immigrant Abner Louima while in police custody in 1997; Schwarz was accused of luring Louima to the room where the assault took place. Taking over the case after the death of Judge Eugene Nickerson, Raggi found it to be “a very challenging case, because nobody had actually seen the assault. We needed to know that the jurors could put aside their biases, both pro and con.” They ultimately reached a split verdict with Schwarz found guilty of perjury. She denied a request for leniency and gave him the maximum sentence of five years.

Another high-profile case she tried, United States v. Gazi Abu-Mezer, involved domestic terrorism— before the Sept. 11 attacks. The defendant nearly succeeded in planting pipe bombs on a New York subway train.

“He was a very challenging defendant,” said Raggi. “His trial was making a political statement, using the courtroom as theater. And the defense attorneys came up with a theory under which he would be acquitted. But he insisted on taking the stand himself, and admitting he had made the bombs—even saying that he meant to kill as many Jews as possible. You could see he had no interest in acquittal, and I gave him life imprisonment.”

When asked to recall a more lighthearted moment on the bench, she referred to a criminal case where the defendant pleaded guilty, which required a “litany” of follow-up questions. Asked if he’d taken drugs within the past 24 hours, the defendant shot back “No, sweetheart”—which caused one of his attorneys to elbow him in the ribs. Judge Raggi was unfazed: “When you’re looking at someone who can put you in the slammer for 20 years, there are worse things you can call them than ‘sweetheart.’”

Watch the HLS interview with Judge Raggi: