A report issued on April 26 by the Presidential Committee on Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery recounts in detail the many ways Harvard University participated in, and profited from, slavery, and the long history of discrimination against, and exclusion of, Black people by the university long after slavery was abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment.

In a statement to the Harvard Law School community shortly after the release of the committee’s report, Dean John F. Manning ’85 commented on the report and the law school’s own connections with slavery, and he announced several initiatives to honor and commemorate the enslaved people whose labor generated wealth that contributed to Harvard Law School’s founding and to better understand the legacy of slavery and the as yet unfinished business of advancing racial justice.

“[T]hough it is difficult, indeed heartbreaking, to read in cumulative detail the pervasive and grievous wrongs committed here at our university, only by honestly reckoning with this history can we together find new ways to make meaning of our past,” said Manning.

“We must also do these things in part because of the distinctive roles that law and the legal profession, at their best, can play in furthering the highest ideals of law and justice,” Manning wrote, stating that the law school must recommit itself to remedying the ills of “racism, inequality, and many other injustices that continue to this day in our society.”

“To build a more just future, we must confront not only our own past but the ways in which law failed to rectify, and at times itself gave rise to, injustice. And we must find inspiration in the memory of the enslaved people whose contributions have for too long been unseen, unheard, and unacknowledged,” he added.

Manning also focused on the ways in which Harvard Law benefited from wealth generated by enslaved people. “Based on findings earlier this century by scholars studying Harvard Law School’s history, this community has grappled for more than a decade and a half with the painful history associated with our founding,” he said.

Referring to the fact that a gift by Isaac Royall Jr. — who earned his money through the labor of enslaved people — endowed the Royall Professorship that helped establish the law school in 1817, Manning wrote: “Our school was . . . founded with wealth generated by the labor of enslaved people. If we are to be true to our complicated history, we must shine a light not only on the many good things our institution has contributed over two centuries, but also on our failings and our wrongs.”

Related: Harvard Law retires shield

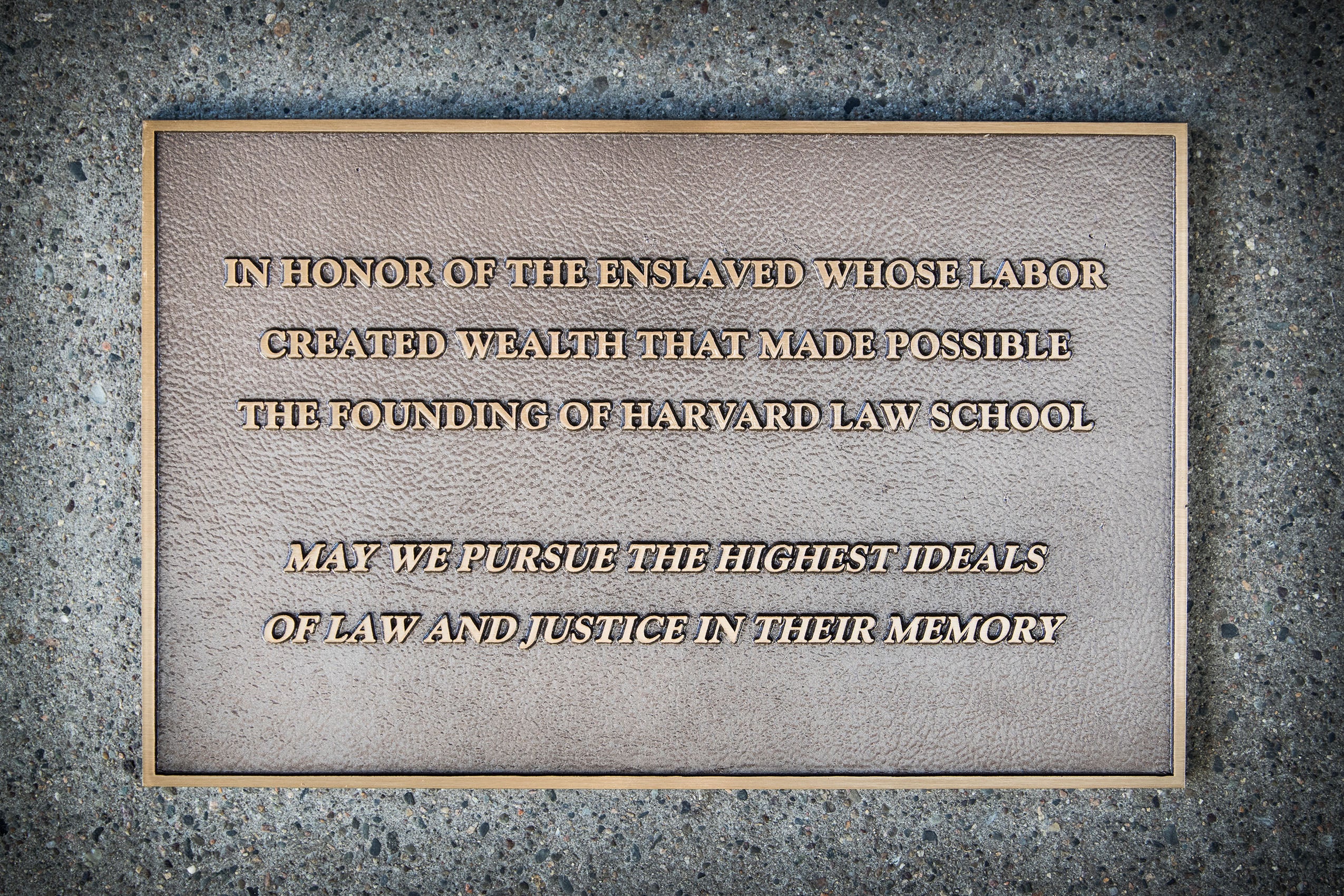

As part of the process of confronting Harvard Law School’s history and honoring the enslaved people whose labor contributed to its creation, the dean announced three initial steps. First, in commemoration of Belinda Sutton and other enslaved people, the courtyard adjacent to Harkness Commons has been renamed the Belinda Sutton Quadrangle, which will be home to a commemorative installation honoring Sutton and other enslaved people. Sutton, a woman enslaved on the Royall estate, lodged a historic series of legal petitions with the Massachusetts General Court to claim her rightful pension from the estate of Isaac Royall Jr. after her emancipation. And the installation will highlight her voice and moral vision.

Second, Manning said that the law school will sponsor the Belinda Sutton Distinguished Lecture and the Belinda Sutton Academic Conference, which will be administered through the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice. It will, he wrote, “feature speakers and topics that advance our understanding of the legacy of slavery and expropriation and the ongoing pursuit of racial justice.”

Finally, the Royall Chair, funded by Royall’s original bequest and most recently held by Professor Halley, will be retired. Manning noted that through her scholarship and teaching, Halley “has heightened awareness of the Royall family’s involvement in the history of enslavement in Colonial Massachusetts and Isaac Royall Jr.’s connection to [the law school]. The dean also announced that Halley has resigned from the Royall Chair, which will never be occupied again.

To continue Halley’s important work, Manning wrote that the law school will seek to build a closer relationship with the Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford, Massachusetts and will work with the museum “to identify opportunities to provide support, further common research interests, and plan regular occasions for students, staff, and faculty to visit the museum for reflection and learning.”

Related: Harvard Law School unveils memorial honoring enslaved people who enabled its founding

The Committee on Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery was established by Harvard President Larry Bacow J.D./M.P.P. ’76 in 2019. It is chaired by Radcliffe Institute Dean Tomiko Brown-Nagin, who is also the Daniel P.S. Paul Professor of Constitutional Law at HLS. Its membership also includes Annette Gordon-Reed ’84, the Carl M. Loeb University Professor, and former Harvard Law School Dean Martha Minow, the 300th Anniversary University Professor.

The committee’s more than 100-page report details Harvard’s many ties to slavery and its legacy and lays out seven recommendations for moving forward, all of which were accepted by Bacow.

“We are an institution of higher education dedicated to research and to the dissemination of knowledge,” Brown-Nagin told the Harvard Gazette. “We are also, in our own motto, dedicated to truth. What we have done here is pursue truths that are painful. But the reality is that even when the truth is painful, we must seek it, we must divulge it, we must set an example of pursuing truth. And that is what we’re doing through the scholarship in this report.”

“We lead with a commitment to leveraging expertise in education to try to address systemic inequities that affect descendant communities in this country and beyond. The remedies are designed to last in perpetuity … [and] will enable generations of students, faculty, and staff to participate in bringing to life our commitment to addressing the legacies of slavery,” she added.

In an email to the Harvard University community unveiling the committee’s findings and recommendations, President Bacow and members of the Harvard Corporation wrote, “Harvard’s history includes extensive entanglements with slavery. The report makes plain that slavery in America was by no means confined to the South. It was embedded in the fabric and the institutions of the North, and it remained legal in Massachusetts until the Supreme Judicial Court ruled it unconstitutional in 1783. By that time, Harvard was nearly 150 years old. And the truth is that slavery played a significant part in our institutional history.”

Bacow also noted that Harvard’s connections to slavery did not end with its abolishment in the Bay State. “The legacy of slavery, including the persistence of both overt and subtle discrimination against people of color, continues to influence the world…,” he wrote. “I believe we bear a moral responsibility to do what we can to address the persistent corrosive effects of those historical practices on individuals, on Harvard, and on our society.”

In addition to having served on the panel that researched and wrote the report, Minow will also lead the new implementation committee. “I can’t think of a better person to lead this effort,” Brown-Nagin told the Gazette. “Her committee will consider how to institutionalize Harvard’s commitment to addressing the harms of slavery.”

In recent decades, Harvard scholars and students have been working to uncover the University’s ties to slavery. At Harvard Law School, the report notes, Professor Halley explored the history of slave-owning colonial benefactor Isaac Royall Jr., sharing knowledge that helped spur student protests decrying the law school’s shield, which featured the Royall family crest. Professor Halley’s work built on the work of Daniel Coquillette, the Charles Warren Visiting Professor of American Legal History, and Bruce Kimball, professor emeritus of educational studies at Ohio State University. As Harvard Law School dean, Minow established a committee that recommended the retiring of the shield, and the shield was retired in 2016.

In the fall of 2017, at the start of Harvard Law School’s Bicentennial observance, Dean Manning and members of the law school community dedicated a memorial to the enslaved people whose labor generated Royall’s wealth. And in 2020, Dean Manning established a working group of faculty, students, alumni, and staff, led by Professor Gordon-Reed, to research and develop a new shield for the school. The Law School unveiled its new shield in 2021.