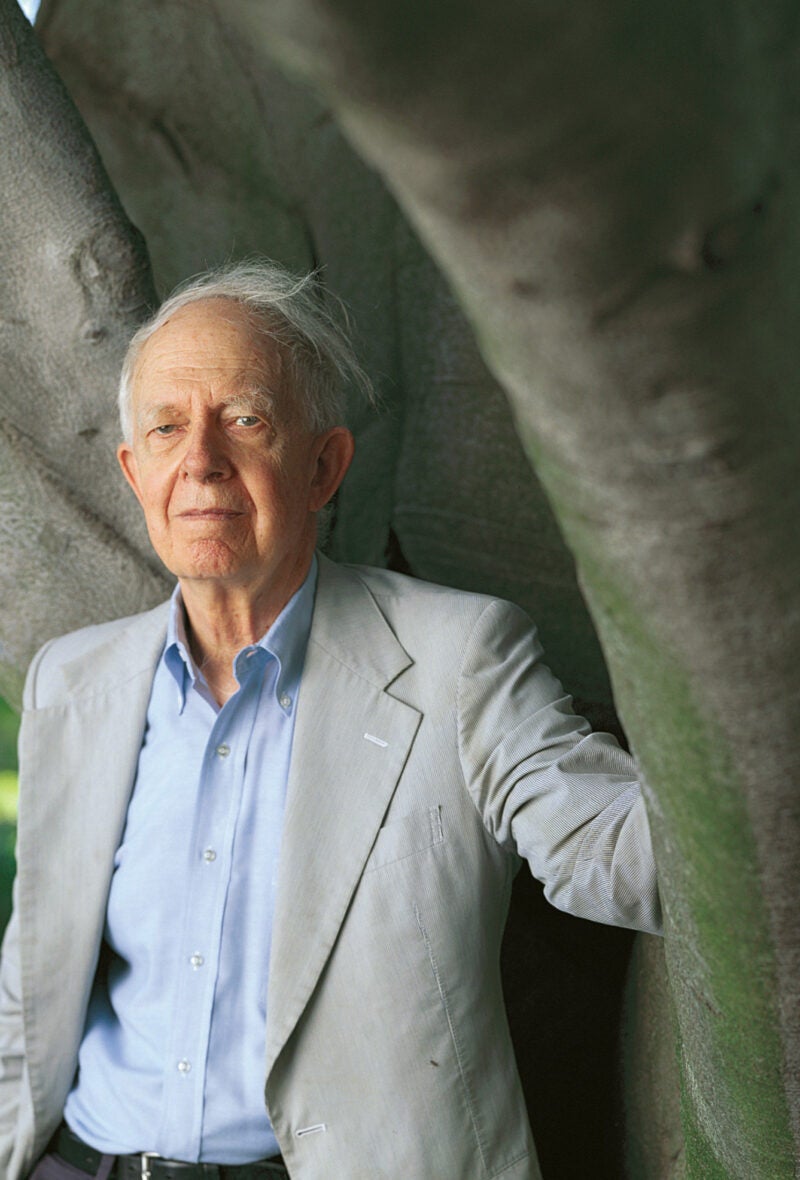

I was privileged to be a student of Detlev Vagts’ while I was obtaining my master’s degree and to work with him as his research assistant after graduating in 1991. Several years later, Vagts served on my Ph.D. committee at my alma mater in the Netherlands. Consequently, I feel myself to be in a good position to attest to the legacy of this gentle giant.

Vagts’ career at HLS spans a whopping 46 years, a half-century in which the law school underwent many changes. Having received his education at both the college and the law school, he is truly a “Harvard man.”

Born of an American mother and a German father who fled Nazi Germany, Vagts grew up in Washington, D.C. After his graduation from HLS in 1951, he entered private practice with Cahill Gordon & Reindel in New York City. He sometimes reminisced about his days on Wall Street in his Corporations class, predicting his students might be confronted with this or that question in their offices overlooking the Hudson River in the wee hours of the morning. I remembered this when I had that very experience as a fledgling attorney in New York.

Vagts was recruited by HLS the old-fashioned way. One day, he received a call from Dean Griswold inviting him to join the faculty. And so he became an assistant professor of law in 1959 and received tenure in 1962. He has been Bemis Professor of International Law since 1984.

The breadth of Vagts’ expertise is truly amazing, ranging from public international law to comparative lawyering and professional responsibility, and from international business transactions to securities regulation and corporate law. He has co-written two coursebooks from which teachers and students will profit for many years to come: “Transnational Legal Problems” and “Transnational Business Problems.” In a legal world that has come to be dominated by specialization, Vagts has managed to remain a formidable generalist.

Vagts’ articles have also contributed greatly to legal thinking. “The International Legal Profession: A Need for More Governance?” (American Journal of International Law, 1996) has been particularly influential. It addresses problems pertaining to professional behavior in international litigation. The article’s powerful plea for regulating international lawyers (including arbitrators) continues to influence today’s debate.

A likely highlight of his career was his 1993 election as co-editor-in-chief of the American Journal of International Law, the leading publication in the field. He served with great distinction.

His works and teachings show the marks of a fine comparative law tradition. In the face of strong U.S. unilateralist and even isolationist tendencies, Vagts displays an unwavering belief in the rule of international law, and the notion that no nation can claim to be above it.

My favorite recollection among the many moments that we have spent together remains the visit that he and his wife, Dorothy, paid to my native Holland in connection with the formal defense of my doctoral thesis in June 1994. He thoroughly enjoyed the pomp and circumstance associated with doctoral ceremonies at Leiden University–especially the nightly festivities at my fraternity. In the thank-you note that I received from him afterward, he commented that he had not experienced such excitement since V-J Day in 1945!

While he certainly is “part of the pantheon of godlike leading citizens who define the Harvard Law School,” as former Dean Clark once described Vagts’ late international law colleague Abram Chayes, he is anything but an ivory-tower person. He is revered, especially by the foreign students enrolled in the LL.M. program, for being a warm and modest person.

Like so many of his students over the years, I experienced his kindness many times. When I was still single and working for a Wall Street law firm, he contacted me one day and invited me to spend the Thanksgiving holiday with his family at his lovely house in Cambridge. In the past 14 years, I have made it a habit of looking him up, either at his Hauser Hall office or at home, whenever I am in the Boston area. This has resulted in a special friendship that I will cherish forever.

It is to be expected that Detlev Vagts’ retirement will not mark the end of his remarkable career. I am confident that it will not silence his voice–a voice of reason and passionate commitment to the belief that international law and institutions are the greatest hope for peaceful resolution of conflict. It is a voice the world needs to hear and to heed.