In the 1930s, Clarence Hickman, an engineer at AT&T’s Bell Labs, invented the answering machine and magnetic tape — decades before they became everyday staples of modern communications. Why the delay between the inventions and their eventual production? Hickman was forced to put aside his inventions almost as soon as he had invented them, when AT&T executives became convinced that the release of recording devices would cause Americans to abandon the telephone.

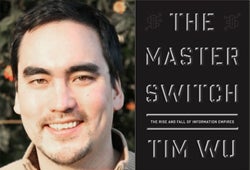

In a talk at Harvard Law School last week, Timothy Wu ’92 opened with the Hickman story to introduce a discussion of his new book, “The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires” (Knopf) [see video below]. Wu, a Columbia Law School professor and a visiting professor at HLS for January term, told the standing room only audience that AT&T is an exemplar of American communications monopolies, both through its support of innovation—possible because of its absolute control of the telephone lines—and its fiats shutting innovation down. And he sees AT&T’s growth as typical of the American information industries, a pattern he describes as “cycling between periods of great openness and entrepreneurial activity” and periods of consolidation, monopolization, “what we can generally refer to as a closed market structure.”

Tim Wu speaks about his new book “The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires.

According to Wu, telephone companies were among the hot start-up industries of the first decade of the 1900s. But that all changed when AT&T created a lasting monopoly that ruled American wire communications for almost 70 years. Radio had a similar genesis, he said. In the 1920s it was an industry of low start-up costs; clubs, churches, and schools were some of the owners of radio stations. In the beginning, the movie industry was equally decentralized and chaotic.

New inventions, Wu told his audience, are the seeds that lead to these periods of openness and utopian vision, and they are always accompanied by great hopes for the future—“a sense that things will be different now.” This, he says, is what people felt after the invention of the radio. “There was a sense that finally God had given man a way to overcome the barriers between us. … How could there possibly be war, misunderstanding and conflict when we are all linked by radio waves?”

What leads from these open, hopeful periods into closed periods, he said, is the rise of a single individual or band of charismatic moguls who arrive in an industry that has been in an open state for 10 or 15 years—long enough for consumers to be interested in more security and reliability, higher production values, “a little less amateur hour,” he said, quoting Apple’s Steve Jobs. Historically, these individuals promise and deliver better products. AT&T offered a telephone connection that worked all the time. NBC offered better radio broadcasting, better content and actors, “everything we associate with mainstream entertainment.” The film industry—initially open, chaotic, highly diverse, producing movies of wildly varying quality—was transformed by the founder of Paramount pictures through “full vertical integration,” said Wu: theaters, production and distribution, were all taken over by Paramount, and this led to the introduction of sound, color, etc: “everything we think of as Hollywood.”

The closing of these industries doesn’t happen as “some kind of authoritarian takeover,” said Wu. Most of the monopolists in history, he contends, have delivered “a golden age of unprecedented creativity of a certain kind—less diversity but innovation. … Frankly just a great product.”

Wu debates the issue with Thomas Hazlett of George Mason University at a Jan. 13 event at HLS.

Wu is known for having coined the phrase Net Neutrality. His other books include “Who Controls the Internet? Illusions of a Borderless World” with HLS Professor Jack Goldsmith. The question at the heart of his new book is whether the same pattern might apply to the Internet as to other information industries or “whether we have flipped some kind of digital switch that makes everything different.”

Wu listed arguments on both sides. During the question and answer period following the talk, HLS Professor Yochai Benkler ’94, faculty co-director of the Berkman Center for Internet and Society, asked about modes of resistance.

Wu replied that addressing resistance to this cycle is in our hands. “I am not someone who believes that just because something has happened before it is inevitable that it will happen again,’ he said. “It may require the overcoming of preferences or habits that are so deep seated that it will be difficult—the desire for convenience or the tendency to worship power and size being almost biological—but I nonetheless believe [the cycle] can be overcome.”