“The wrongs which we seek to condemn and punish have been so calculated, so malignant, and so devastating that civilization cannot tolerate their being ignored.” So said United States Supreme Court Justice and U.S. Chief of Counsel to the International Military Tribunal, Robert H. Jackson, during his opening statement for the prosecution at the first of 13 Nuremberg Trials, which began 80 years ago, on Nov. 20, 1945.

For decades, the Harvard Law School Library has been working to make the nearly complete set of Nuremberg Trials records publicly available online. It launched the first version of Harvard’s Nuremberg Trials Project website in 2003, but until recently only roughly 20 percent of the Law School’s trove of Nuremberg materials had been accessible to online visitors. Today, the full collection of 140,000 documents comprising more than 700,000 pages is live and searchable by anyone around the globe.

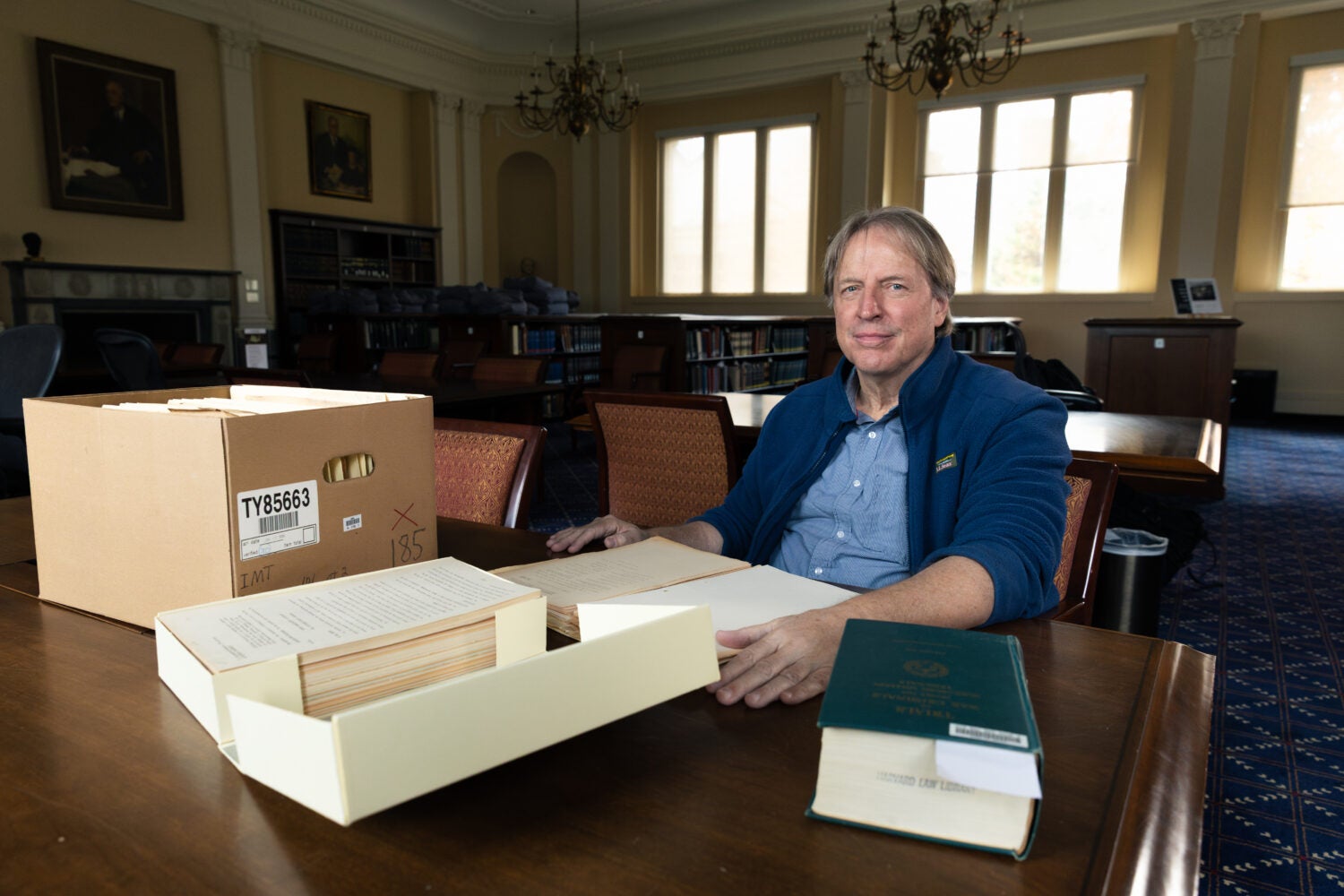

Harvard Law School Library’s Paul Deschner, who has helped guide the project almost since its inception, spoke with Harvard Law Today about the scope of the archive and what it took to bring the entire collection online.

Harvard Law Today: Can you give me a sense of the breadth of material contained in the now fully online collection?

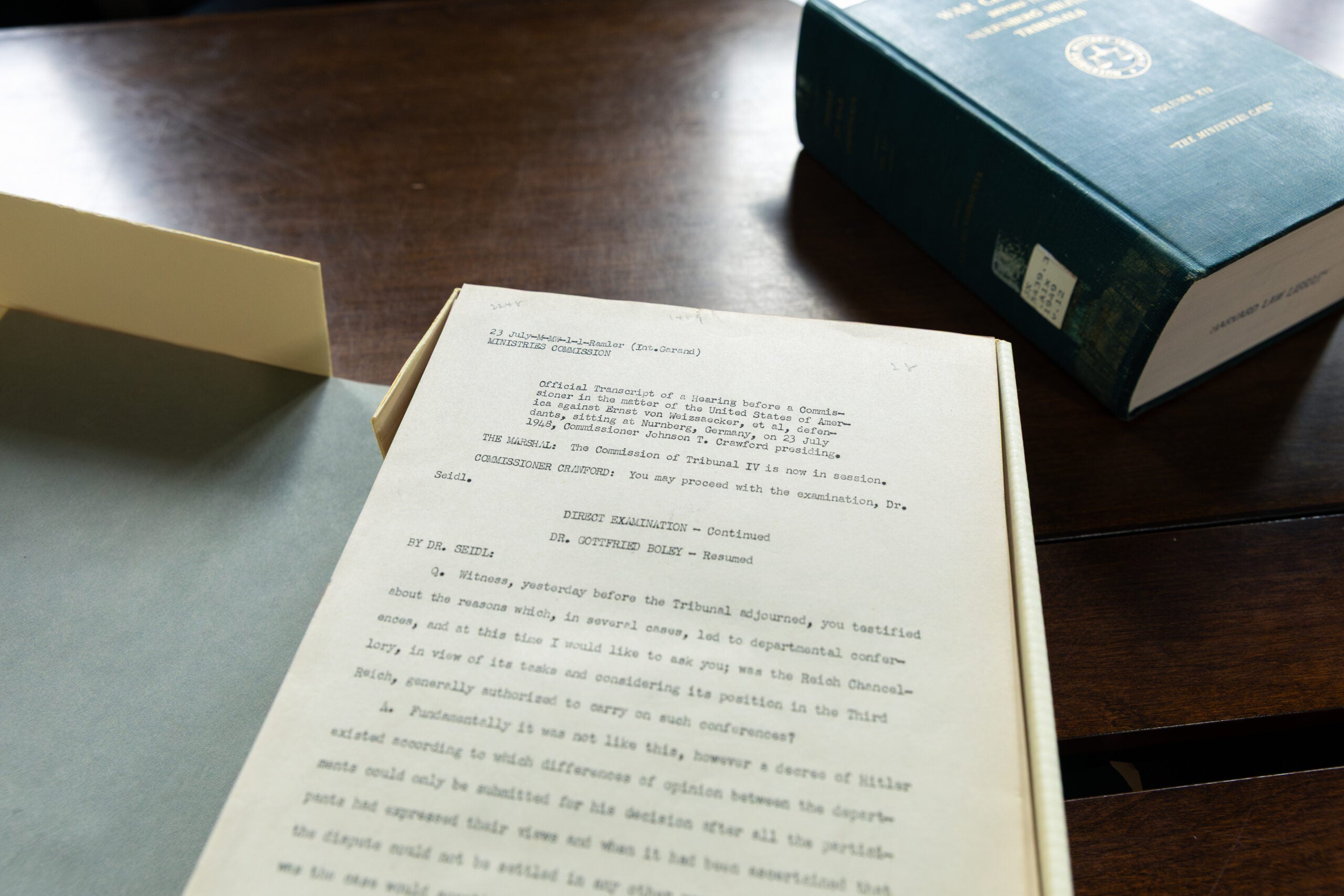

Paul Deschner: It was actually explicitly stated in the first trial by the head of the prosecution team that this was to be a trial by document because there was so much of it — essentially judging the Nazis by their own documentation because they were so thorough in recording everything that they did. There were witnesses that testified, of course, and there were lots of affidavits that were created during the course of the trials to get further witness voices, particularly on the part of the of the defense. But it was the material from the government ministries and other sources where they were clearly stating everything that formed the basis of the prosecution.

Our collection includes virtually every written form of human communication you can imagine — there is a lot of correspondence, top level Nazi officials writing to each other about aspects of policies that they were implementing. There are memoranda and minutes of meetings including some critical documents of meetings in the late ’30s where Hitler was laying out his plans. There are minutes of a meeting in early 1942 in Berlin where all of the ministries are represented at which an official introduces the Holocaust as a policy. You have a lot of excerpts from newspapers, and from journals of various kinds. You have diaries, telegrams, maps, photographs, organizational charts of the Nazi hierarchy, and even a procurement plan for armaments. It runs the gamut.

It’s extraordinarily varied stuff. And it’s not just legal historians, but anybody who’s interested in the cultural analysis of that whole period, who would find rich materials to work with. If you’re a sociologist or historian or psychologist, it’s the whole cross section of human behavior from a lot of different perspectives. It’s not just government memoranda talking about policies.

HLT: Who is the key audience for these materials?

Deschner: Initially, it was thought that the main people coming to the site would primarily be researchers with expertise in international criminal law or in that particular historical period. But thanks to the responses from people who had had exposure to that first iteration of the website in 2003, it became clear that there were many others also interested—from middle schoolers and high school students to those who had personal connections with people who were involved in the trials, or people who suffered from the events themselves.

HLT: Do other organizations have the same range of material?

Deschner: The National Archives might have the most complete collection of this material. But they don’t really have very much online. When they got the materials, just like Harvard and many other institutions did in the late ’40s and early ’50s, they attempted to make these materials available to the public. But, at that time, the way you did that was through microfilming or on-site visits. There obviously was no digital option at that point to make it available the way people expect nowadays, through the internet. They did as much as they could and produced various publications that dealt with certain trials, but they haven’t yet gone beyond that, so we are really the only project that tries to make the full collection available and searchable on the web for anyone to access.

HLT: Can you describe what has been involved in making this material available online?

Deschner: The scanning actually began back in 1998 when a pilot project of the first trial — the Medical Trial — began and it was done through the imaging services offered in the basement of Widener Library. And they did an absolutely brilliant job. But at the time, it was inordinately expensive to make single camera snapshots of all these document pages. That was one of the major challenges for the project — when you scaled up to the whole collection and you calculated what the cost was, it was just prohibitive.

But in 2014-15, the technology that was made available to the project made it possible to scan everything in the course of a couple years, using a high-speed scanner, which dramatically lowered the cost. And those are the scans that we’re using today.

There was a team at the law library’s Digital Lab who carried out the work, who had the task of taking the paper materials in whatever format they were and preparing them for scanning. A lot of them were stapled or otherwise fastened together, and they had to be disassembled. And you had transcripts in bound volumes, requiring the cutting of bindings so that they could be fed into the high-speed scanner. It was a challenging operation. The team did a wonderful job. And thanks to them, we now have all the images, absolutely every single image of every document that comprised the collection.

HLT: But scanning the documents was only the start. Can you share a little about the effort to produce descriptive text for each document — to provide the metadata that makes them more easily searchable by visitors to the website?

“It’s not just legal historians, but anybody who’s interested in the cultural analysis of that whole period, who would find rich materials to work with [through the Nuremberg Trials Project].”

Paul Deschner

Deschner: During the early years of the project, it was decided that there should be a fairly rich template for describing each document, specifically for the most important documents in the collection, the ones that were used as submitted evidence during court sessions. The project organizers felt that the collection, and those trial documents in particular, warranted that sort of attention and granularity to support user access.

In addition to the kind of terms anyone who has used a card catalog is familiar with — title, author, heading — document analysts provided a short summary for each document, subject headings, transcript document citations and scholarly notes. That’s very time consuming and requires a fair amount of domain expertise and also project expertise — the kind of context built up over the course of your experience with the collection. It has been slow going, but that sort of attention to detail was committed to from the beginning, and we’ve maintained that commitment ever since.

HLT: How has AI helped you do this work?

Deschner: We’ve used it in a couple of ways. It has been immensely useful for writing software to do data analysis, manipulation and storage — huge parts of our work. It allows me to focus more on higher-level data questions and requirements and not have to devote as much time to implementation. It also looks very promising as a tool to convert text images to machine-readable, searchable text of the contents. But accuracy is extremely important, and we’re still researching dependable ways to identify and fix places where current AI tools skip a beat. Once you do have high-quality machine-readable text, then you can start asking interesting questions about authorship, document creation date, keywords and request summaries. The potential upside is huge.

HLT: What difference does having full-text search make?

Above all, it has helped to make searching the archive far more flexible. Previously, the way you would connect to a document was by searching the descriptive information for each document. You were limited to what somebody else thought about the document, and whatever sort of summary and descriptive information they came up with. And if your search terms didn’t match the descriptive terms provided, you would not be able to connect with the document.

Now, with full text available, you’re not limited to that. If Hermann Goering was not deemed important enough in a particular letter, let’s say, to be a part of a descriptive title, then you were not going to connect via that name with that document. But now, as long as he’s mentioned in the document anywhere, all you have to do is search on it and it’s going to connect. So, it’s a huge addition to the way we’re making these things discoverable.

HLT: You’ve been with this project almost since the beginning. What’s it like to see this project come full circle?

Deschner: It’s so nice because in 2003, when we launched for the first time, we had very little to actually post online, but the international reception was stunning. I don’t think anybody on the team was expecting that there would be major news organizations picking up on it and publishing articles. Everybody was saying it was so wonderful that we had the Nuremberg Trials documents online. But people didn’t always read the small print or didn’t go to the website and see that we only had ten percent of the collection up. So now, finally, it’s great to be able back up that initial vision and put all the trials online.

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.