In order for a democracy to survive and thrive, the places where people work also must be democratic, according to Yolanda Díaz Pérez, Spain’s second vice president and minister of labour and social economy.

“If you spend half of your life in a place where you don’t have a voice, where you can’t influence the decisions being made that affect your health, your time, your salary, your dignity, and your future, then democracy stops being a shared experience and becomes something distant, almost alien,” she said. “Democracy isn’t just an institutional system. It’s a way of organizing life in common.”

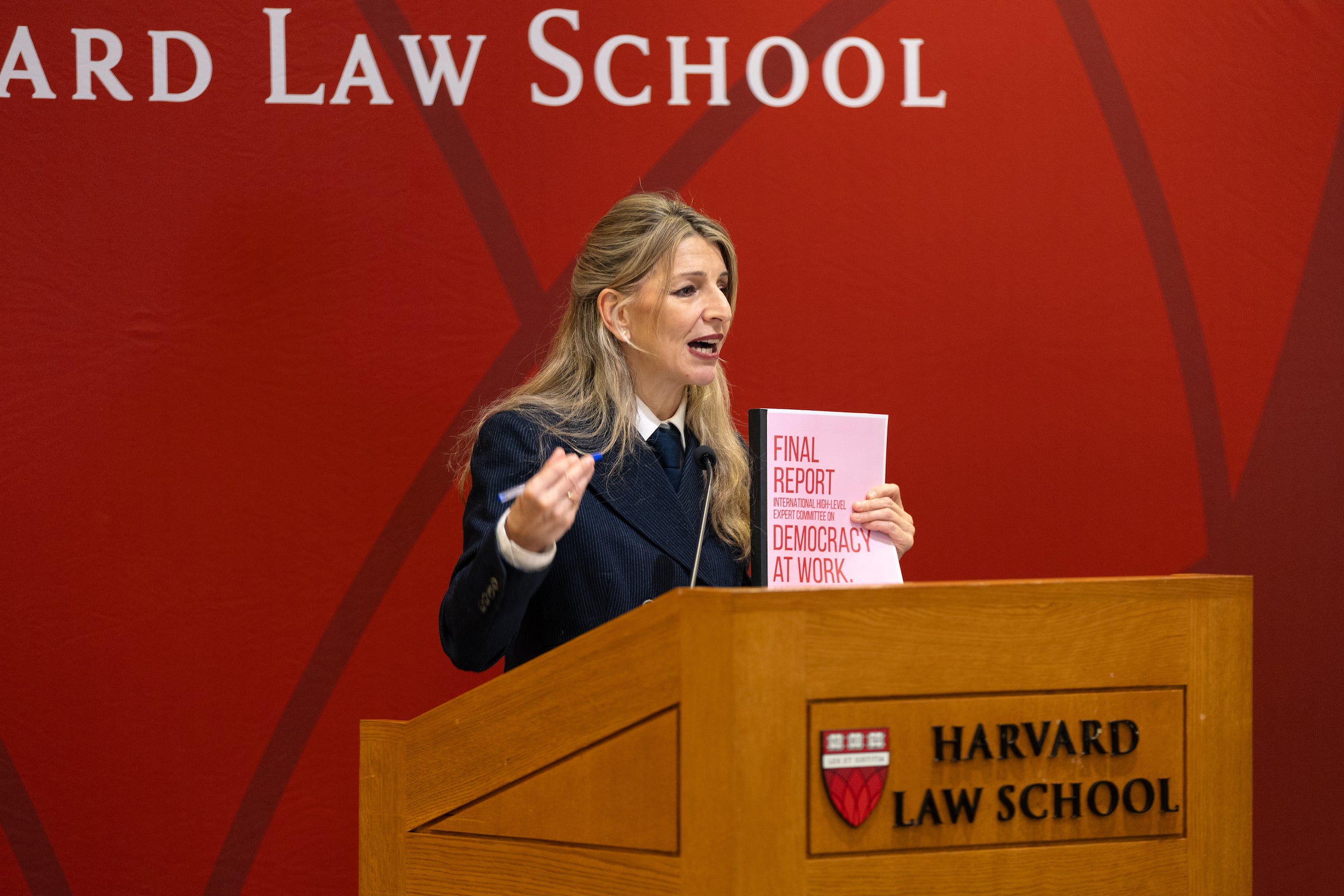

Díaz spoke at the John T. Dunlop Memorial Forum Lecture, presented on Feb. 4 by the Center for Labor and a Just Economy and its Harvard Trade Union Program. She was introduced by the center’s executive director, Harvard Law School Professor of Practice Sharon Block; Harvard Kennedy School Visiting Professor David Weil; and Isabelle Ferreras, a professor at the University of Louvain in Belgium, a 2005 alumnus of the trade union program, and a senior research associate at CLJE.

Block noted Díaz’s leadership in passing Spain’s Rider Law, which requires online delivery platforms to classify their workers as employees.

Díaz has been “lauded for not looking for the easy or incremental policy solutions,” Block said. “She is recognized for pushing for transformative, structural change towards a more just and labor-centered economy.”

In her wide-ranging remarks, Díaz spoke in support of workers and offered her criticisms of rising inequality, the growing power of technology companies, and what she described as the autocratic practices in the United States and elsewhere. Her speech came just two days after her office released a “democracy at work” report called “Two Promises to Those Who Work: Voice and Ownership.”

“If you spend half of your life in a place where you don’t have a voice … then democracy stops being a shared experience and becomes something distant, almost alien.”

Yolanda Díaz Pérez

Ferreras led the expert committee that issued the report, which offers recommendations for how Spain can empower workers and address growing crises, including a lack of succession planning among small and medium businesses, threats from the rise of artificial intelligence, and high working poverty rates (13.7 percent and twice that for immigrants).

Ferreras said Díaz is “leading with science at her side.”

“If you want to build a vibrant democratic society, you have to care for what is happening in the workplace,” Ferreras said.

The report is the culmination of a year-long effort by a 13-member committee that sought, at the Spanish’s government’s request, to implement part of the nation’s constitution concerning labor practices that says the government “shall effectively promote the various forms of participation in the firm” and “facilitate workers’ access to ownership of the means of production.”

In addition to Ferreras, Harvard was represented on the committee by Kennedy and Business schools Professor Julie Battilana.

Among the report’s suggestions were requiring worker participation in operational decisions at companies; setting minimum employee ownership rates (2 percent for companies with more than 25 employees, and 10 percent for companies with more than 1,000 employees); and creating a reporting tool that links corporate benefits such as subsidies and some tax rates to performance on measures of worker participation and ownership.

“Those who create value should also participate in its control and in its results,” Díaz said. “This report is a roadmap for returning power to those who work.”

Díaz linked efforts to empower workers with her country’s major decision last month to grant legal status to hundreds of thousands of immigrants who live in Spain without authorization. Eligible immigrants will be granted a year of legal residency and permission to work.

“Democracy always has to be a project of hope, of making the future better for people,” she said. “It’s very important that we don’t think only of the negative. We can’t think only about stopping the extreme right. We have to provide an exciting project that people feel is their own.”

The Dunlop Lecture is named for the longtime Harvard professor who served as secretary of labor under President Gerald Ford and advised many presidents dating back to Franklin D. Roosevelt. In his introductory remarks, Weil said Dunlop would have welcomed Díaz’s remarks.

“John was deeply interested in comparative industrial relations,” said Weil, who studied under Dunlop at Harvard. He added that Dunlop believed in the “importance of bringing people together in a system of capitalism that could represent workers who were less empowered than the employers who they worked for.”

“I’m not sure what John would make of the world we are in at this perilous moment,” Weil said. “He really believed if you brought people together and worked through what he called the ‘common fact base’ you could get good outcomes from that and sustainable outcomes and outcomes that were appropriate for a democracy.”

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.