Sabrina Singh ’20 has been an active member of the human rights community during her time at Harvard Law School, including leading the Harvard Human Rights and Business (HuB) Student Association for a year and working in the International Human Rights Clinic for the past two. In addition to her human rights concentration, she has worked to be a voice for international students at Harvard Law School, cofounding the Coalition for International Students and Global Affairs (CISGA), with Ayoung Kim ’20. Born and raised in Nepal, Sabrina has been speaking out about how the COVID-19 pandemic could exacerbate conditions in her home country. The Human Rights Program (HRP) spoke with her recently to learn more about her background, what drew her to human rights, and how she is continuing to advocate for vulnerable populations during this time of uncertainty.

Human Rights Program: Why did you decide to specialize in human rights at Harvard Law School?

Sabrina Singh: My introduction to law school was as an undergraduate summer intern at the Office of Public Interest Advising (OPIA). That summer, I had the opportunity to interview a human rights lawyer, and I asked her why she chose her career. She said that she loved to be able to fight for what she knows to be good. Her conviction and energy stuck with me as I eventually came back to HLS as a student.

HRP: What kind of work have you been doing in the International Human Rights Clinic?

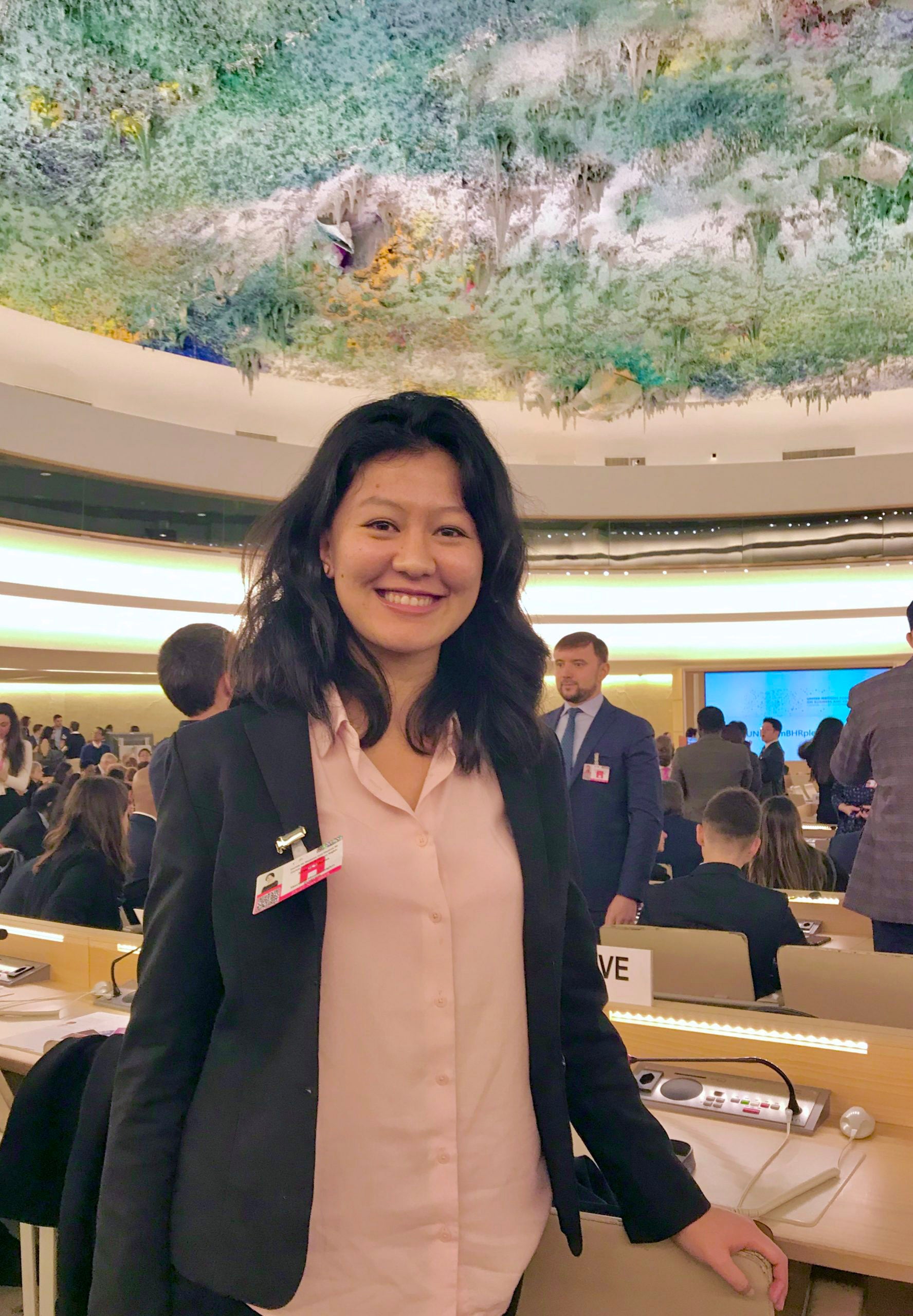

Singh: I have focused on business and human rights (BHR) and economic, social and cultural (ESCR) rights. I had the opportunity to work on BHR clinical projects with [HRP and International Human Rights Clinic Co-director and Clinical Professor] Tyler Giannini and [former visiting clinical instructor] Amelia Evans LL.M. ’11. With their clinical teams, I researched and helped write a report on multi-stakeholder initiatives, which are global governance bodies set up to create human rights standards for corporate actors; I also helped facilitate a BHR communities training for human rights practitioners in New York; most recently, I worked on a project on the cocoa industry in Ghana. Last year, I had the opportunity to attend the UN Forum on Business and Human Rights in Geneva, which brings together more than a thousand participants who gather to take stock of the BHR field. The theme was ‘government as catalysts for business respect for human rights,’ but one of my principal takeaways was how underrepresented local and grassroots communities are in these spaces.

HRP: What lessons have you internalized from this work and your instructors in the clinic that you hope to carry forward?

Singh: Tyler and Amelia have helped me understand how important it is to look at the human rights implications of economic growth and globalization. [International Human Rights Clinic co-director and clinical professor] Susan Farbstein [’04] was an amazing mentor for my paper titled, “Realizing Economic and Social Rights in Nepal,” which will be published in the forthcoming edition of the Harvard Human Rights Journal. That paper seeks to understand what role the judiciary can play to realize basic social and economic rights in a post-conflict context. In a poor country like my own, I often hear people ask, ‘What is the relevance of seemingly abstract human rights law when our day-to-day material needs like food and housing are not met?’ I believe human rights law can and must speak to issues such as poverty, hunger, health care, housing, and economic inequality on a global scale.

HRP: You originally moved to the United States from Nepal for college. How have you remained connected to your community back home?

Singh: Cofounding HLS’s international student group [the Coalition of International Students and Global Affairs] and serving on the boards of Human Rights and Business as well as the Law and International Development Society have been ways to stay connected to the international issues that matter to developing countries and certainly to Nepal. I am a part of Nepal Rising, a 501(c)(3) non-profit that mobilized the Nepali diaspora for relief efforts after the devastating earthquake in Nepal in 2015. I am also a co-founder of a growing Nepali women’s collective that has expanded to four cities in the United States. Ours is the first generation of Nepali women to be receiving higher education and career opportunities at an unprecedented global scale; our collective exists to document our experiences and create solidarity among us.

HRP: How is the COVID-19 pandemic affecting Nepal? What particular issues are important for the local and international community to know?

Singh: COVID-19 has laid bare the inequities happening on a global scale. My home country is a case in point. First, many people lack access to basic social and economic rights like health care and social security. There are very few hospitals where you can get tested for COVID-19 in the country. We likely have less than 500 ICU beds. Many are likely to slip back into abject poverty with the economic downturn, particularly the 70 percent of the labor force in the informal economy. We have already started to hear some anecdotes about food scarcity on the ground. Second, responses to the pandemic have often not respected basic human rights. About 1,500 Nepali migrants leave every day for wage labor in the Middle East and East Asia. Some do critical work in factories that produce medical equipment to fight COVID-19. Migrant workers are the backbone of the global supply chain. But many of them have lost their jobs in the past few weeks. At the same time, Nepal instituted a nationwide lockdown and closed its borders, even to its own citizens. Migrant workers are now literally stuck, some sleeping on roads and others trying to swim across a river to come back home.

HRP: How are you trying to raise attention to these issues?

Singh: At Nepal Rising, in collaboration with local partners, we are now raising funds to help build the health care system in Nepal to prepare for COVID-19, such as by procuring PPE and training healthcare professionals on how to use them. Former US Ambassador to Nepal, Scott DeLisi, is one of our partners for this initiative. We are trying to keep abreast of daily developments and coordinate with other initiatives in civil society. The diaspora and the international community can play a critical role when a fragile state or LDC [least developed country] has a looming public health and economic crisis.

HRP: Finally, how are you coping from day to day? How is balancing the daily work of HLS, keeping abreast of the news cycle, and trying to work on behalf of Nepal Rising?

Singh: I am precariously fine. It feels anticlimactic to not have a physical commencement and bar exam this summer, but trying to be an advocate for my community helps me too. I got breakfast from the Hark this morning. An individual in the dining staff told me that she is a single mother with three kids and that she is extremely worried about what will happen to her kids if she contracts the virus. So, I feel a mix of anxiety, gratefulness, and solidarity.