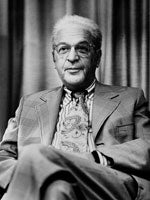

Benjamin Kaplan, the Royall Professor of Law Emeritus at Harvard Law School and a former justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, died August 18, 2010.

A pre-eminent copyright scholar, Kaplan co-wrote the first casebook on copyright, with Yale Law Professor Ralph Brown ’57 in 1960. His 1967 seminal text, “An Unhurried View of Copyright,” grew out of a series of lectures on copyright he delivered at Columbia as part of the James S. Carpentier Lectures series. Kaplan served on the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court from 1972-1981 and later on the Massachusetts Appeals Court.

“Ben Kaplan was a towering giant in the law with legendary wisdom and analytic precision,” said Harvard Law School Dean Martha Minow. “The generations of students and litigants guided by his work as professor and justice ensure that his legacy will long endure.”

In 1947, Kaplan joined Harvard Law School as a visiting professor, teaching a section of Real Property. He later taught the first-year course in civil procedure, an advanced procedure course, and Copyright and Unfair Competition. In partnership with Professor Richard H. Field ’29, he redesigned the procedure course, centering it on the Federal Rules and bringing in material from Evidence and Constitutional Law that had not traditionally been included. The visit turned out to last a quarter of a century, during which Kaplan developed his long-standing interest in procedure and intellectual property, became the Royall Professor of Law and had a lasting influence on generations of students and legal scholars.

“Sometimes one is lucky enough to have a teacher who changes one’s life,” said HLS Professor and Vice Dean for Academic Planning Andrew Kaufman ’54. “Ben Kaplan was such a teacher and I was his lucky student. He taught me how to think critically about law and life.”

David Shapiro ’57, the William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Law, Emeritus, at Harvard Law School said, “Ben Kaplan’s wisdom and wit, and his mastery of the art of teaching, have been an inspiration to me as a student and throughout my academic career. Like the many others who have had the good fortune to work with and learn from him, I treasure the experience — the wonderful combination of rigor and encouragement, of skepticism and faith. He will be sorely missed.”

From 1960 to 1966, he served as reporter to the Advisory Committee on Civil Rights of the Judicial Conference of the United States and later as a committee member.

Kaplan left HLS in 1972 to become an associate justice of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts. He served until 1981, when he reached the constitutional age for retirement. He later was recalled to the Massachusetts Appeals Court in 1983.

In a 1988 profile for the Harvard Law School Bulletin, Kaplan said: “Each appellate case presents itself as a puzzle. The challenge is to find the one right solution, and to explain it in a way that satisfies not only the Bar and the specialists but also the general intelligent public. There is not much difference in the end between judging and teaching. The job of the judge, like that of the teacher, is to instruct, to educate.”

Among Kaplan’s students at Harvard were future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer. Among his former law clerks are Cass Sunstein, Administrator of the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs.

Kaplan graduated from Columbia Law School in 1933, and he began his general law practice with the New York firm Greenbaum, Wolffe & Ernest. He participated in the civil rights case Hague v. C.I.O., which reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1939.

In 1942, he joined the U.S. Army working in military procurement in a Pentagon office, and he ended his tour of duty as a member of Justice Robert H. Jackson’s prosecuting staff in the first Nuremberg case. He briefly returned to law practice in New York before accepting a 1947 invitation from Dean Erwin Griswold to teach at Harvard Law School.

Kaplan was married to the late Felicia Lamport Kaplan. He is survived by his son, James Kaplan, a daughter, Nancy Mansbach, four grandsons, and five great-grandchildren.

Obituaries for Kaplan also appeared in The New York Times and the Boston Globe.