The use of generative artificial intelligence threatens to exacerbate an already challenging time for human rights globally, according to Harold Hongju Koh ’80, a Yale Law School professor who has held prominent posts in the U.S. Department of State and been a leading contributor to conversations about how international law should apply to modern technologies.

On its own, AI raises serious ethical concerns, including well-documented problems with bias and the technology’s massive use of energy and water resources. And with authoritarianism rising around the world, Koh said, including in the U.S., AI has the potential to serve as a “gigantic megaphone” for misinformation campaigns (including so-called deepfakes), to aid surveillance, and to target perceived enemies.

Speaking on Nov. 13 at a Harvard Law School session called “Human Rights Under Stress in the Age of AI,” Koh was introduced by former classmate Gerald L. Neuman ’80, the school’s J. Sinclair Armstrong Professor of International, Foreign, and Comparative Law and director of the Human Rights Program, which sponsored the event.

A leading international law expert and practitioner, Koh was legal adviser at the Department of State from 2009 to 2013 and U.S. assistant secretary of state for democracy, human rights and labor from 1998 to 2001. He currently represents Ukraine in various international law proceedings.

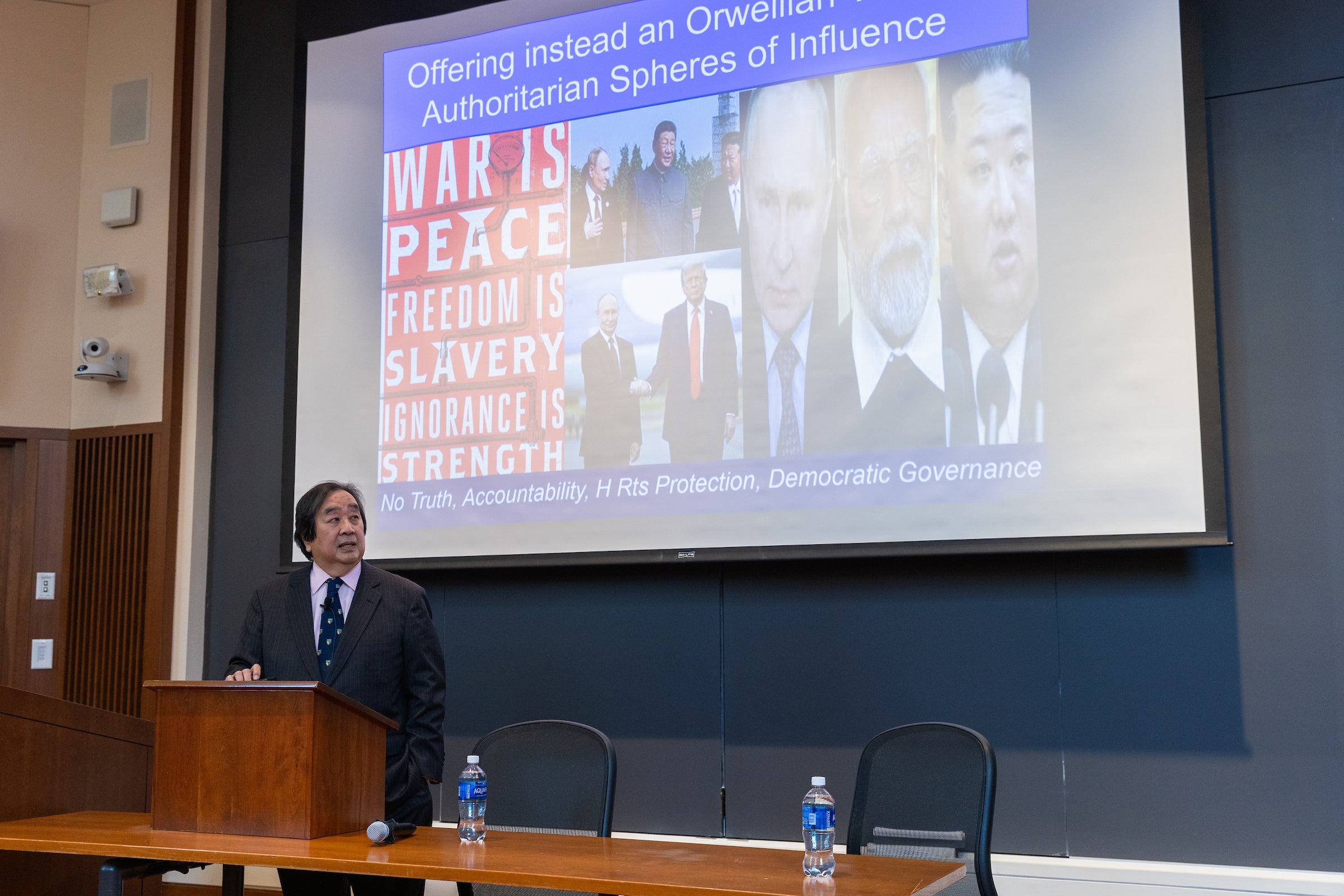

International law can play a role in protecting people from human rights abuses caused or enhanced by artificial intelligence and in holding states accountable, Koh said, but states need to agree to common principles and understandings first. That is increasingly difficult, as some states are attacking the very foundations of international human rights law, including truth, accountability, and democratic governance.

“[The concept of human rights] is being attacked by a whole group of authoritarians … that is surrounding and filling the gaps created by America’s nonparticipation.”

The concept of human rights — “international rights, held by all against all” — was an “astonishing proposition” when it was formally developed in the wake of World War II, Koh said.

“Today, that vision is being attacked by a whole group of authoritarians … they seem to be developing a league of autocrats that is surrounding and filling the gaps created by America’s nonparticipation,” he said.

Koh is part of a group of international law experts who during the COVID-19 pandemic formed the Oxford Process on International Law Protections in Cyberspace. They produced several statements, each signed by more than 100 leaders in the field, that clarified how international law applies to cyber operations, including in areas such as health care, elections, and infrastructure. The group also plans to address AI concerns.

“Various groups were developing these norms … they were all stalemated,” he said during the Q&A portion of the event. “So, we thought, ‘Why don’t we just do this in a grassroots way?’”

Since then, he said, the United Nations has quoted the group’s work.

“When … governments are faced with legal norms firmly declared, they tend to accept them,” Koh said. “You can’t beat something with nothing. Having a set of rules that a bunch of people have signed off on is helpful.”

Koh also addressed the possible development and use of lethal autonomous weapons and their impact on wars. Drones — operated by humans — are already ubiquitous in conflicts, including in Russia’s war against Ukraine.

“Where we are headed is video-game wars,” he said. “War will become the cheapest option. If war is the cheapest option, and diplomacy is more difficult and more expensive, then we will have perpetual war.”

“Where we are headed is video-game wars. … War will become the cheapest option. If war is the cheapest option, and diplomacy is more difficult and more expensive, then we will have perpetual war.”

Koh suggested that an agreement modeled after the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Treaty might be possible and that any such treaty would require a “last clear chance” principle stating that the person with final approval of any action could be held accountable for the results. Koh noted that dozens of states have signed on to the Political Declaration on Responsible Military Use of Artificial Intelligence and Autonomy issued by President Joe Biden’s administration in 2024. The document aimed “to build international consensus around responsible behavior and guide states’ development, deployment, and use of military AI.”

Koh stands by the principles he set forth in 2001, which he summarized as telling the truth; being consistent toward past, present and future human rights violations; and building stronger systems to prevent atrocities in the first place.

He ended his talk with a story of an experience in Kosovo when, as assistant secretary of human rights, he was asked to swear in three new judges. They did not want to be sworn in on a religious text or any documents from Serbia or Yugoslavia. Instead, they chose to place their hands on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the European Convention on Human Rights.

“One of these guys said to me, ‘In this troubled world, this is the only faith we share,’” Koh said. “And so, I think that remains true. In a time where human rights is under stress in an age of AI, this is still the only faith we share. We have to do our best to maintain it.”

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.