A Legendary Teacher, in the Classroom and on the Bench

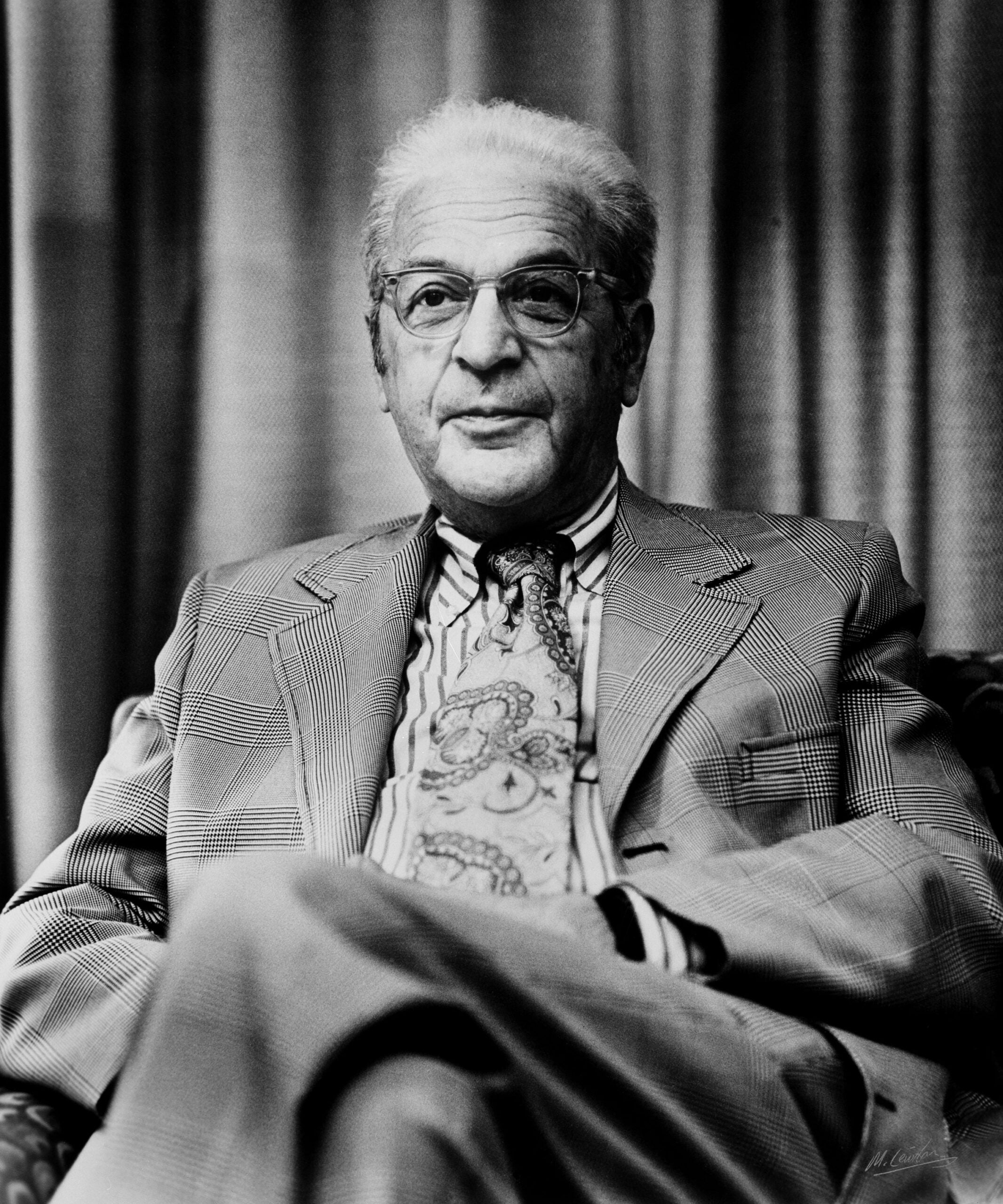

Benjamin Kaplan, the Royall Professor of Law Emeritus at Harvard Law School and a former justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, died Aug. 18, 2010.

A specialist in civil procedure and a preeminent copyright scholar, Kaplan co-wrote the first casebook on copyright, with Yale Law Professor Ralph Brown ’57 in 1960. His 1967 seminal text, “An Unhurried View of Copyright,” grew out of a series of lectures he delivered at Columbia Law School.

“Ben Kaplan was a towering giant in the law with legendary wisdom and analytic precision,” said Dean Martha Minow. “The generations of students and litigants guided by his work as professor and justice ensure that his legacy will long endure.”

Kaplan first joined Harvard Law as a visiting professor, in 1947. The visit turned out to last a quarter of a century, during which he developed his long-standing interest in civil procedure and intellectual property, joined the permanent faculty, and had a lasting influence on generations of students, legal scholars and jurists.

“Sometimes one is lucky enough to have a teacher who changes one’s life,” said Professor Andrew Kaufman ’54. “Ben Kaplan was such a teacher, and I was his lucky student. He taught me how to think critically about law and life.”

Professor David Shapiro ’57 said of his former teacher: “Ben Kaplan’s wisdom and wit, and his mastery of the art of teaching, have been an inspiration to me as a student and throughout my academic career. Like the many others who have had the good fortune to work with and learn from him, I treasure the experience—he was a wonderful combination of rigor and encouragement, of skepticism and faith.”

Kaplan’s students also included two Supreme Court justices, Stephen Breyer ’64 and Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’56-’58.

At a memorial service that filled Ames Courtroom in October, Breyer called Kaplan “the master of us all.”

“To listen to Ben teach,” he added, “was to listen to the Socratic method at its best, used by a first-rate craftsman and articulated by a true gentleman.”

Breyer also recalled how beautifully Kaplan wrote, but he praised above all, “the quality of his thought and analysis, his integrity, his humanity that animates his opinions and assures us that they will last.”

Kaplan graduated from Columbia Law School in 1933, and he began his law practice with the New York firm Greenbaum, Wolff & Ernst, participating in the civil rights case Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organization, which reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1939.

In 1942, he joined the U.S. Army, ending his tour of duty as a member of Justice Robert Jackson’s prosecuting staff in the first Nuremberg case. Working first with Col. Telford Taylor ’32 and then with Jackson, Kaplan played an important role in drafting the indictment in the case.

In 1972, Kaplan left the Harvard Law faculty to become an associate justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. He served until 1981, when he reached the constitutional age for retirement. He was recalled to the Massachusetts Appeals Court in 1983.

In a 1988 profile in the Bulletin, Kaplan said: “Each appellate case presents itself as a puzzle. The challenge is to find the one right solution, and to explain it in a way that satisfies not only the Bar and the specialists but also the general intelligent public. There is not much difference in the end between judging and teaching. The job of the judge, like that of the teacher, is to instruct, to educate.”

“He imbued in us respect for the majesty of the law”

A recollection of Ben Kaplan from a former student

Of the many legal greats who graced the halls of Harvard Law School and brought fame and acclaim to Cambridge, one stood out above the rest—the late Ben Kaplan, former justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (1972-1981) and Royall Professor of Law Emeritus at HLS.

At Ben’s recent funeral in Chilmark, Martha’s Vineyard, the eulogies were more a glowing tribute to the man, his wit, his wisdom and the universality of his greatness, than a lamentation of his passing.

The burial service took place under cloudy, sodden skies. Many of those present to pay respect to Ben were accommodated under a hastily erected tent. Midway through the service, the skies darkened and heavy rain came. It was as though the legal heavens were shedding tears for a truly beloved colleague.

My own association with Ben Kaplan began as a timid first-year student at Harvard Law School. Ben was our contracts teacher. But he taught us much more than that which could be gleaned from Lon Fuller’s casebook. He imbued in us respect for the majesty of the law and shared with us the mysteries and mystique of the judicial process. More than that, he instilled in each of us his abounding enthusiasm for teaching and learning law.

No doubt he left some of us (myself included) questioning whether we would ever be able to comprehend and appreciate the message he was delivering to us—not on a silver platter—but rather in a form we had to reach for.

His favorite question during class, one which I unabashedly adopted during my own 26-year law school teaching career, was “What’s my next question?”

Toward the end of what was likely the last class of a yearlong course, Professor Kaplan asked if there were any questions. It was his style to place a mark next to the name of each student on the seating chart to indicate the number of times that person was called upon or spoke during the year. The space next to my name was as clear and pristine as it was the first day of class. When I raised my hand, it was with a rather quizzical tone that Professor Kaplan asked if I had a question. In a very meek voice, giving vent to my fears and trepidation, I asked: “Is it too late to drop the course.”

He responded without missing a beat, “I’ll tell you after I grade your exam.”

I was fortunate enough to have a summer house near Ben’s home on the Vineyard. Over the course of the next 30-some years, I was able to spend many hours with him. I relished each minute. My appreciation, respect and unabashed admiration grew with each visit. I join the throng who will miss him terribly.

Fortunately, my sadness will be overcome by the joy of his friendship and the memories of our time together.

Albert L. Cohn ‘51

Sept. 9, 2010