More than a year before the U.S. presidential election, a team of researchers from the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society joined forces to study and map political media coverage. In the months leading up to the election, they tracked and analyzed significant topics, including the politicization of the pandemic and false claims about mail-in voter fraud.

Led by Yochai Benkler and Rob Faris, the team followed political discourse online, uncovering media strategies and shedding light on the media ecosystem in the United States. Benkler, the Berkman Professor of Entrepreneurial Legal Studies and co-director of BKC, and Faris, a senior researcher at the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy, spoke about their work at a recent event moderated by Jasmine McNealy, a faculty associate at BKC and associate professor at the University of Florida‘s College of Journalism and Communications.

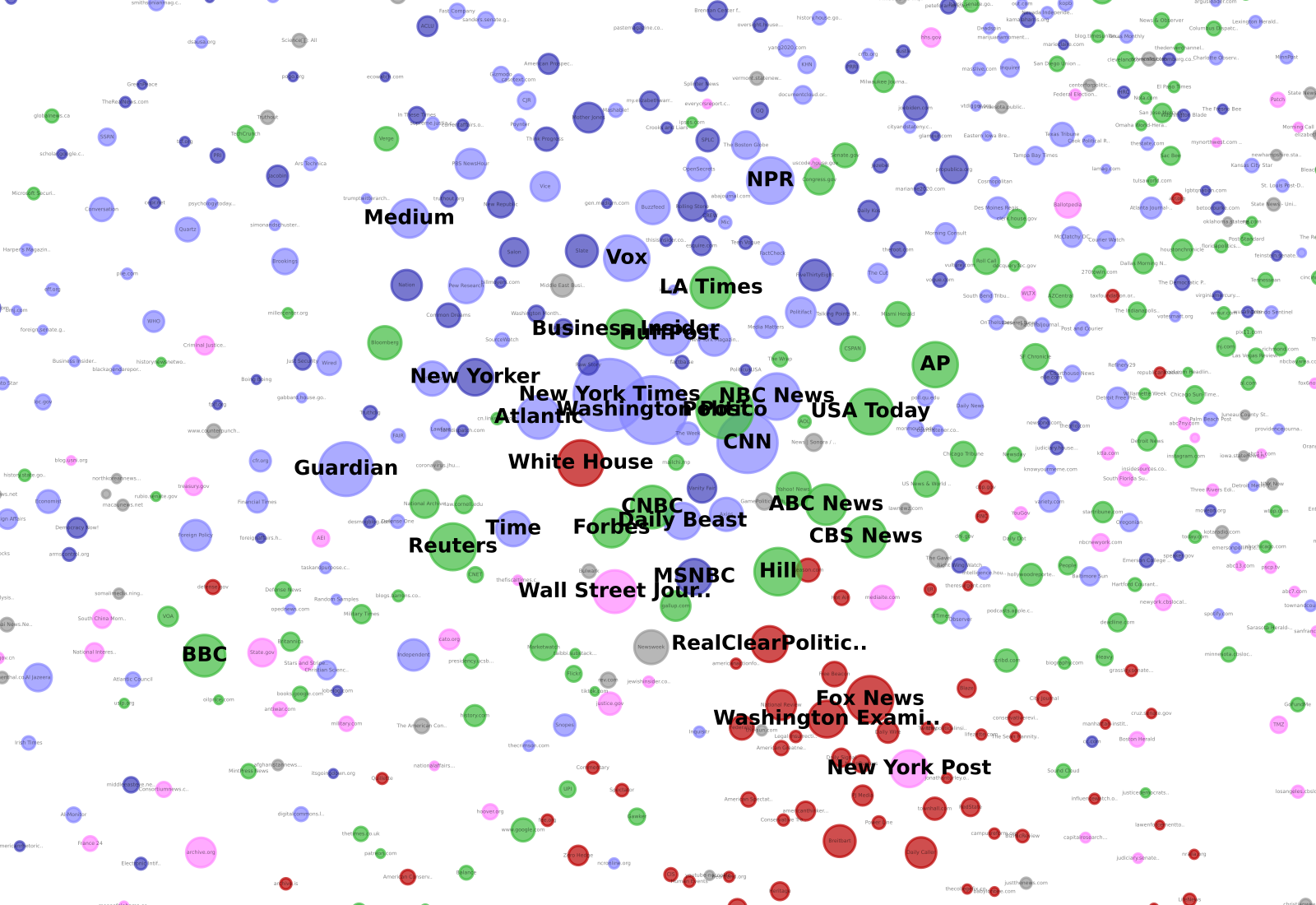

The team’s studies are grounded in their previous work on the 2016 election, which showed using linking patterns between online news sources that media sources from the right exist in a cluster, isolated from the media outlets from the center and left. The resulting network structure illustrates asymmetric polarization in the U.S. media ecosystem. Their book, “Network Propaganda,” written with Hal Roberts, highlighted how the outlets from the center and left follow traditional journalistic norms and fact-checking, but outlets from the right do not follow those same norms.

Network map based on links between media outlets. Red dots represent outlets from the right; pink is center-right; green is center; light blue is center-left; and dark blue is left.

Using more recent data from Media Cloud, an open-source tool for media analysis, and data from Facebook and Twitter, they show that this dynamic persisted and formed the backdrop of the 2020 election. They also found that mainstream media continue to play an important role in political discourse. Their reports thus far provide a comprehensive analysis of political discourse starting in January and running through May, and a separate study on disinformation about mail-in voting fraud.

Mail-in voter fraud propaganda is elite-driven through mainstream media. It’s not just Trump. It is a partisan strategy designed to prevent and suppress the vote.

Yochai Benkler

Faris summarized some of the main strategies from the right-wing media during the early months of the year: “One is to divert attention to news that is more favorable to your side in the face of bad news. Another is to rebut and reframe negative coverage coming from the center and center-left. Another is to discredit sources of negative information, whether it be individuals or institutions,” he said.

One difference between the 2020 election and the 2016 election is the mainstream media‘s response to efforts from the right to spread and frame narratives, Faris explained. “In 2016, as we documented in ‘Network Propaganda,’ the right-wing media and conservative activists had a lot of success in setting the agenda across the media ecosystem. First looks—particularly related to impeachment and Hunter Biden and the Ukraine conspiracy—suggest this is no longer true, at least not to the same extent in 2020, that mainstream media was much more wary of picking up the talking points coming from the right.”

In their analysis of media coverage specifically about mail-in voter fraud, they showed that the spread of disinformation was primarily top-down and was abetted by mainstream media and Republican elites.

“Mail-in voter fraud propaganda is elite-driven through mainstream media. It’s not just Trump,” Benkler said. “It is a partisan strategy designed to prevent and suppress the vote. It is supported on the most highly trusted news media; Sean Hannity on the right, by the chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, by the Senate Majority Leader. What we’re seeing is a much more traditional propaganda system where a major party is engaged in false disinformation, combining it with institutional actions to suppress and depress the vote in critical states in order to overcome their basic electoral limitation.”

Since mainstream media plays such a central role in their findings, McNealy asked Faris and Benkler, “What does it mean for the mainstream media—and particularly for newsroom patterns or newsroom culture—and professional journalists working in this space covering all of the related campaign and extra campaign kinds of information and possible propaganda?”

“It turns out to be extremely difficult for newsrooms to adapt their behavior. They’re used to following the flashy headline. They’re used to trying to attract people to read them. They’re used to being balanced. It’s much easier to say, ‘it’s a partisan debate’ than to say ‘this side is lying, that isn’t and we’re not being partisan, we’re just telling you the truth,’” said Benkler, who also wrote an op-ed for NiemanLab about responsible reporting. “There’s a real need for reassessing the role of the editor for not separating out fact-checking from the main reporting but actually putting the fact-checking in the headline, in the lead, in order to educate the audience from the very start that what you’re hearing is a lie. It’s an intentional propaganda campaign.”

Faris agreed, highlighting the challenges of operating within an asymmetric media ecosystem. “I think in these studies, we see both the strengths and the limitations of elite media,” he said. “We see the limitations in that it’s almost impossible to pierce the armor of loyal partisans, not that we shouldn’t try and continue to hold the truth, but I don’t think that’s going to be where we’re going to see a big impact.”

But, he said, “I do think that we’ve seen progress in avoiding the foibles being played by political operatives,” pointing again to the right‘s narratives about Hunter Biden, including their attempt in October to push another false story. “It was clearly a chapter out of the 2016 playbook that [the right] wanted to repeat, and mainstream media largely said, ‘no thank you, we’re not playing that game again.’”