As a financial analyst at BlackRock a few years ago, Catherine Grace Katz ’22 found she sometimes needed a break from modeling Excel spreadsheets. That’s when she’d take a few minutes to wander down to Chartwell Booksellers, a store specializing in books by and about Winston Churchill, located in the lobby of her midtown Manhattan office building.

Catherine Katz ’22

Katz had studied and written about Churchill’s early years for her undergraduate and master’s theses. Over the course of her coffee breaks, she got to know the shop’s owner, who in turn introduced her to members of the International Churchill Society. “That’s how I learned the family had opened the papers of Churchill’s middle daughter, Sarah,” Katz said during a recent Zoom call from her parents’ home in Chicago. “They were looking for someone to write an article about this new archival collection, which is one of the last of the Churchill family papers to be opened.” She jumped on the assignment.

What Katz discovered would become “The Daughters of Yalta: The Churchills, Roosevelts, and Harrimans: A Story of Love and War,” an intensely researched, vividly depicted nonfiction account of a pivot point in history written from the perspectives of three young women—Sarah Churchill, Anna Roosevelt and Kathleen Harriman (daughter of Averell Harriman, U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union). All three played vital behind-the-scenes roles for their famous fathers at the Yalta Conference, 75 years ago in February 1945. Published in September, the book has been optioned by Amy Pascal, a producer of last year’s “Little Women.”

“I was so struck by the idea that these women, all about my age, had been on the front lines of history,” Katz says. “Think what it would have been like to be in a room with Churchill, FDR and Stalin when you were in your late 20s or early 30s.”

“I was so struck by the idea that these women, all about my age, had been on the front lines of history.”

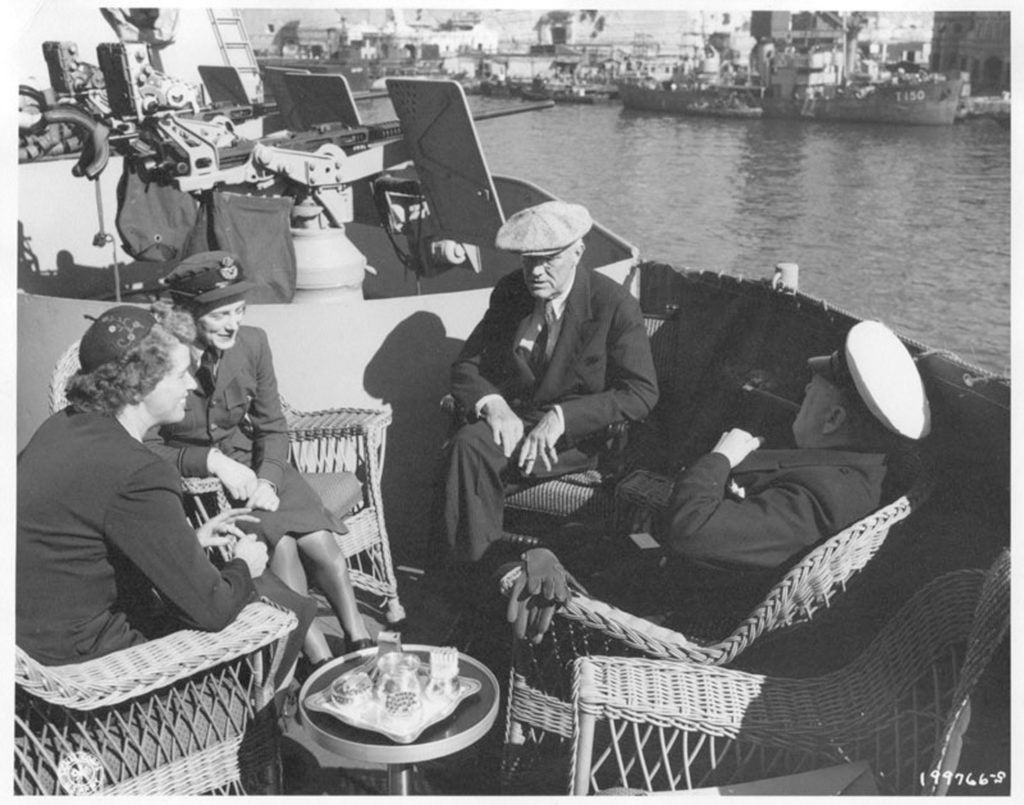

Drawing on multiple sources, including the women’s living relatives, Katz gives readers an intimate sense of the Yalta Conference, an event that would mark the final meeting of Churchill, FDR and Stalin in the concluding months of World War II. (FDR, already in failing health, would die just two months later.) At stake: the Soviet Union’s role in the Pacific, the configuration of postwar Europe and the early foundations of what would become the United Nations, among many other complex points of contention. The pivotal negotiations and outcomes of the conference have been documented and analyzed in enough books to fill a small library. As Katz notes: “You can see the beginnings of the fractured relationship between the Soviet Union and the West that came from some of the decisions made at Yalta. It’s a moment on the precipice between world war and cold war.”

“Daughters” offers a completely new perspective on these familiar proceedings through the eyes of its relatively unknown protagonists. A former war correspondent who had taught herself Russian, Kathleen Harriman oversaw every detail of Yalta’s preparations at Livadia Palace, coordinating with the Soviet advance team to transform a war-ravaged building in the Crimea into a site suitable for three world leaders and the hundreds of people accompanying them. Sarah Churchill was an actress and Royal Air Force officer with an astute mind for politics. She served as a trusted sounding board for her father’s thoughts and frustrations, particularly when it came to maintaining civil relations with FDR. Anna Roosevelt shared a secret known by only her father’s doctor: FDR was slowly dying of congestive heart failure.

“Anna is a very complex character,” Katz comments. “She’s someone who would do anything for her family, and it’s heartbreaking at times to see the situations in which she found herself.” Near the end of FDR’s administration, Anna took an active role in protecting her father, removing briefings and requests she deemed an unnecessary drain on his time and energy. “It makes one really think about the context of politics today and how involved the first family should be in an elected official’s public duties,” says Katz.

Anna was also loyal to FDR despite his longtime affair with Lucy Mercer. And there were liaisons within the group. Sarah Churchill was having an affair with the American ambassador to the U.K., while Averell Harriman was seeing Pamela Churchill, who was married to Winston’s son—a fact Kathleen knew and guarded closely. Shortly before Yalta, Kathleen herself had an affair with Anna Roosevelt’s married brother. With so many secrets—and so much at stake from a larger geopolitical vantage point—trust is an underlying theme in the relationships between all three fathers and their daughters, notes Katz.

Writing the book itself took three years, she says, starting with roughly a year and a half of research from 2017 to 2018 before moving through several drafts. “Pencils down was two days before we learned we were being sent home for coronavirus,” says Katz. “A friend of mine said that in order to do 1L and write the book, I had to be like a shark, still moving while I was sleeping.”

“A friend of mine said that in order to do 1L and write the book, I had to be like a shark, still moving while I was sleeping.”

The depth of character development and heightened sense of narrative scene make “Daughters” read like a novel, but every detail is laboriously backed by multiple primary sources. “I’m often asked how much of the book is from my imagination,” says Katz, “and the answer is, none. If I’ve written ‘the wind was blowing from the east,’ that’s because it was recorded in the weather report or noted in more than one person’s diary. Fortunately, in a story like this, there are a number of meticulous military types who record everything to the smallest detail.”

Katz is taking the fall semester off from HLS to promote “Daughters,” which has already been reviewed in The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. She began a mostly virtual book tour in late September, which included a Zoom conversation about the book with another HLS author, Scott Turow ’78, on Oct. 20, sponsored by the HLS Library. With one year of law school complete, she’s looking forward to exploring interests that tie in to her work as a writer, including copyright law and tax law. “There’s also a larger framework of questioning I’m intrigued by,” Katz adds. “The history I’m drawn to has to do with foreign affairs and international law. As much as I love writing about and studying history, I also want to help us understand how history informs the world today and how we can use that knowledge to move forward in a better way.”