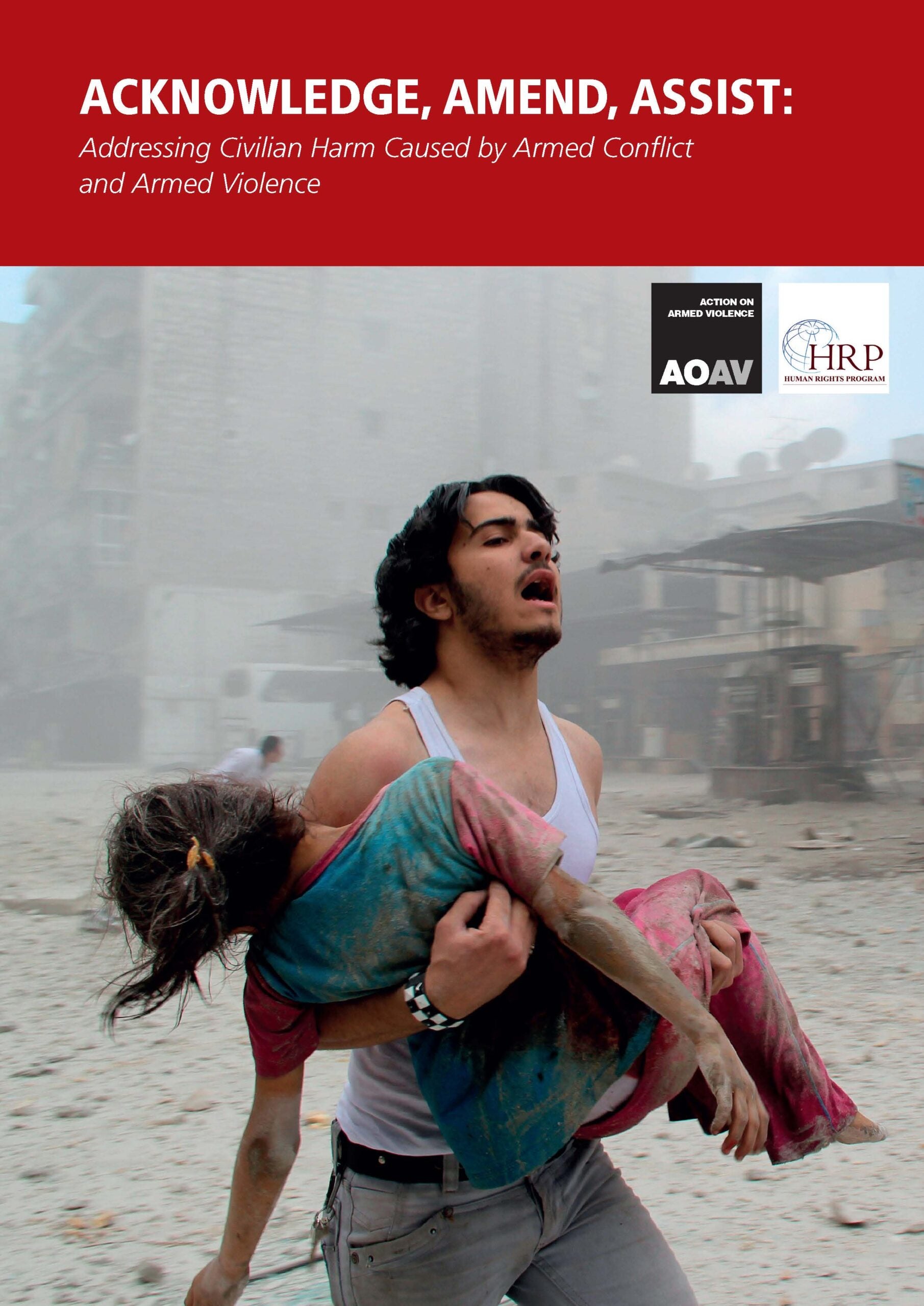

Mitigating the human costs of armed conflict and armed violence has become a moral and legal imperative over the past two decades. Within the international community, several strategies for helping civilian victims have emerged. A publication, released this week by Harvard Law School’s Human Rights Program and Action on Armed Violence (AOAV), seeks to advance understanding and promote collaboration among leaders in the field.

The 28-page report, Acknowledge, Amend, Assist: Addressing Civilian Harm Caused by Armed Conflict and Armed Violence, examines a range of current approaches: casualty recording, civilian harm tracking, making amends, transitional justice, and victim assistance. In so doing, the report illuminates their commonalities and differences and analyzes the difficulties they face individually and collectively.

“These programs all provide valuable assistance to civilian victims, but they have yet to be viewed holistically,” said Bonnie Docherty, editor of the volume and lecturer on law in the Human Rights Program. “A comparative look at the approaches could help reduce overlapping efforts and identify gaps that should be closed.”

Acknowledge, Amend, Assist takes its name and much of its substance from a two-day global summit held at Harvard Law School in October 2013. The event brought experts from government, civil society, and academia together to explore the challenges of meeting victims’ needs and to learn about where their work might coincide and/or conflict. This publication seeks to build upon the momentum generated by the summit and present the issues that it raised to a wider audience.

As the essays demonstrate, the five approaches to addressing civilian harm share not only an ultimate goal but also many overarching principles. In general, they define “victim” broadly, envision a wide range of support, encourage victim participation in the process, and aim to address articulated needs. They recognize that even if one party bears primary responsibility for providing assistance, there may be multiple players involved.

At the same time, the approaches differ in focus and practice. Some concentrate on lawful harm, others on unlawful harm. They also call for various forms of recognition and aid. Distinctions among the approaches that have led to debate include who should bear responsibility for providing assistance and how law can most effectively contribute to the process.

“We hope members of the assistance community will draw lessons from each other’s strategies and consider how to increase collaboration,” Docherty said. “In the long run, more informed, complementary, and coordinated approaches would improve the lot of victims of armed conflict and armed violence.”

[pull-content content=”

HRP hosts symposium on civilian harm caused by armed conflict

Kenneth Rutherford was working as a humanitarian aid worker in Somalia in 1993. He was driving with a colleague through a rural area near the city of Mogadishu on a clear, blue day when his vehicle hit a landmine. The explosion tore through the vehicle.

Rutherford looked to his colleague to his right, who was black, and saw that he had been turned white because he was covered in dust from the explosion. Rutherford’s legs were so badly damaged that both would later have to be amputated below the knee. … What brought Rutherford to Harvard Law School was last week’s Human Rights Program symposium: “Acknowledge, Amend, Assist: Addressing Civilian Harm Caused by Armed Conflict and Armed Violence.” The two-day summit, organized by HLS Senior Clinical Instructor Bonnie Docherty, gathered policy experts, fieldwork leaders and government officials from around the world to try to develop a framework to increase collaboration on assistance to conflict victims. The event was co-organized by Action on Armed Violence, a UK nongovernmental organization. Read more.” float=”center”]