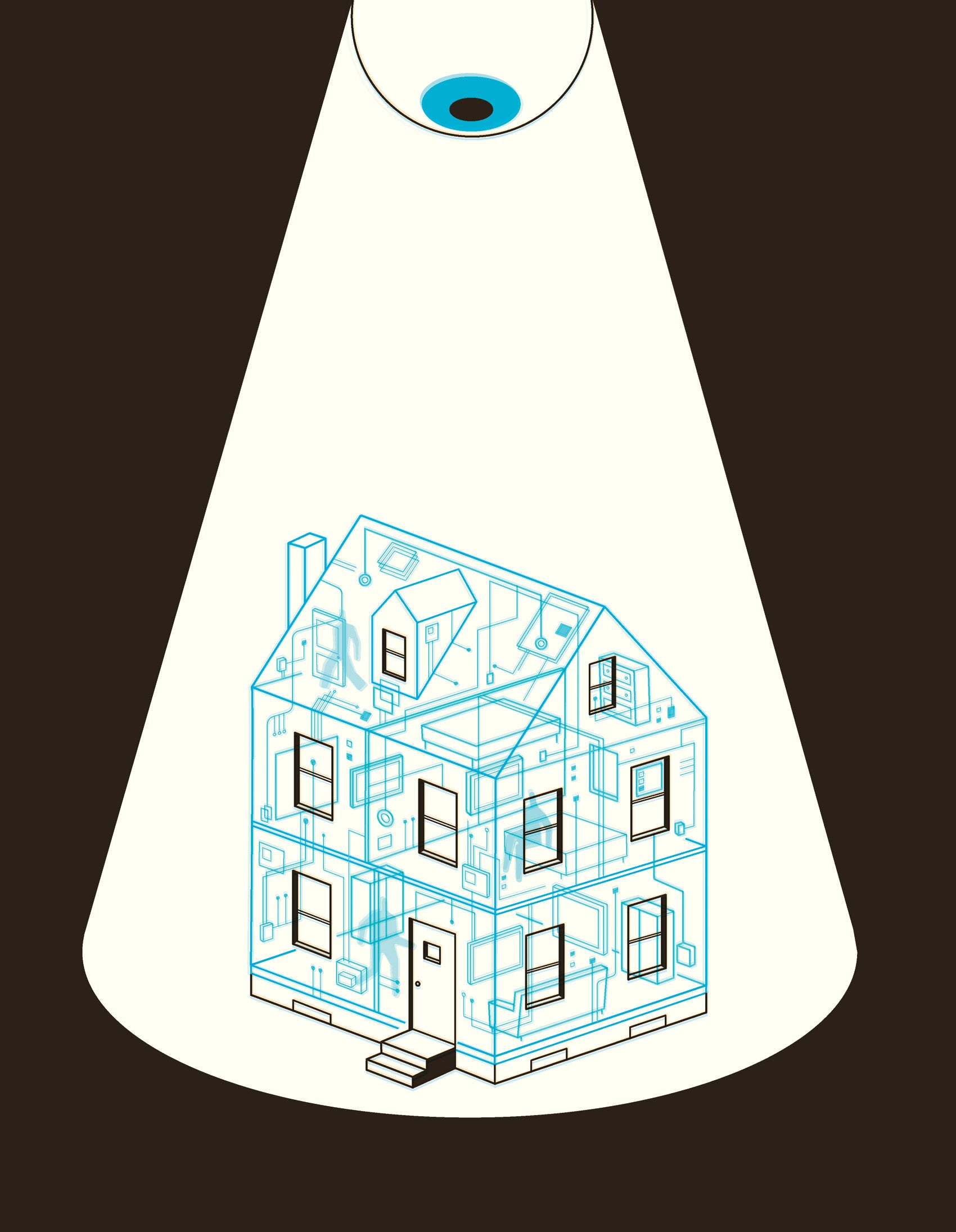

Cellphones may be the least of your privacy concerns

Consider your home in five years: Before you’re out of bed in the morning, the drapes open themselves, the shower turns the water to the perfect temperature, and the toaster toasts your bagel just the way you like. Motion detectors know when you’ve left for work and switch on your home security system as a robot vacuum begins cleaning your floors. At the office, you realize you forgot to start the clothes dryer; a simple voice command to your smartphone means the laundry’s ready when you get home. As you head up the driveway at night, sensors in your smart car alert the garage door to open and the lights in your home to turn on while the TV tunes itself to your favorite program.

Welcome to the Internet of Things. It may be about to change our lives as radically as the Internet itself did 20 years ago.

“Some analysts think this is the future—it’s huge, as big as the Internet and World Wide Web,” says David O’Brien, a senior researcher at the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at HLS. “It’s hard to separate the hype from reality, but signs suggest we’re at the early stages of a tectonic shift.”

The Internet of Things, or IoT, relies on sensors embedded in a wide variety of devices and systems to make your life incredibly convenient while exchanging a stunning amount of very personal information about you via cloud computing.

This technology is already available in everything from home appliances to Fitbits and children’s toys, and over the next 10 years, it is expected to become a multitrillion-dollar industry, according to a report released in February by the Berkman Center, “Don’t Panic: Making Progress on the ‘Going Dark’ Debate.”

All that personal data—just waiting to be mined. The implications for privacy, national security, human rights, cyberespionage and the economy are staggering.

For corporations, the IoT is the golden goose of the very near future, with everyone from Amazon to Nike creating products with cloud-connected sensors—including cameras, microphones, fingerprint readers, gyroscopes, motion detectors, and infrareds—collecting streams of data about your movements, preferences, and habits.

The Internet of Things “has the potential to drastically change surveillance, providing more access than ever in history,” according to a new report by the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at HLS.

For law enforcement, it’s one reason we are entering a “Golden Age of Surveillance,” to use a term coined by Peter Swire and Kenesa Ahmad at the Center for Democracy & Technology in Washington, D.C. The IoT “has the potential to drastically change surveillance, providing more access than ever in history,” says the Berkman Center’s report, the result of a highly unusual gathering of government intelligence officials, think tank experts and HLS faculty who met for a series of off-the-record conversations about cybersecurity over the previous year. Several leaders in the U.S. Senate and House, and key staffers from the White House, have reached out to Berkman about the report, which has also garnered praise from members of the international intelligence community, O’Brien notes.

Human Rights and Encryption

Recently, the FBI and Apple waged a very public battle over the government’s access to encrypted data in an iPhone connected to the terrorist attack in San Bernardino, California, last December, which ended in late March when the FBI, with help from an unnamed third party, cracked the encryption without Apple’s help. But that has not ended the debate raging over the legal status of encryption in telecommunications and other digital devices. The government worries that its ability to protect the country from terrorism and other crimes is “going dark” as a result of widespread “end-to-end encryption” in smartphone operating systems and Internet services—where even the device manufacturers and service providers can’t see customers’ data—while civil libertarians and others say unlocking iPhones won’t solve the problem and in fact will raise serious new dangers such as terrorists hacking into cellphones.

But at the very time the tussle between Apple and the FBI was grabbing international headlines during the winter, the Internet of Things was quietly stepping up to offer an overwhelming treasure trove of information about all of us. In other words, even as the technology gods close an encrypted window or two, they’ve been opening huge, Internet-connected doors.

“The good news and the bad news is that we aren’t ‘going dark,’” says HLS Professor Jonathan Zittrain ’95, faculty director of the Berkman Center and a co-convener of the group, along with Matt Olsen ’88, former general counsel for the NSA, and Bruce Schneier, a cybersecurity expert and fellow at Berkman. “It’s good news because law enforcement isn’t as hamstrung as they may feel. If you look at the digital trails people are laying down, the clear trajectory is toward much more available to someone with a subpoena than ever before,” Zittrain says.

The “going dark” metaphor is the wrong one for several reasons, the group agrees. For one, aside from Apple, most tech companies, including Microsoft and Google, rely on access to unencrypted user data as their primary revenue streams, selling your information to advertisers. In addition, so-called “metadata” about your communications, such as location data from cellphones and header information in emails, is unencrypted and is a useful investigatory tool. Perhaps most importantly, the burgeoning Internet of Things offers a vast array of new opportunities for surveillance through cameras, microphones, GPS trackers and other sensors in your home, in your car, even on your wrist: Police could seek a warrant to track your whereabouts through your Fitbit, say, or watch and listen to you in your home via your baby monitor or Internet-connected TV.

Police could seek a warrant to track a suspect’s whereabouts through a Fitbit.

“There’s a lot of opportunity to learn about a suspect in a way that didn’t exist 20 or even just 10 years ago,” says Olsen, former director of the National Counterterrorism Center, who has been teaching a national security course at HLS this spring.

At the same time, the fact that the cyberworld is not “going dark” is also bad news, Zittrain believes, because the overwhelming amount of personal information floating in cyberspace raises “troubling questions about how exposed to eavesdropping the general public is poised to become,” and how vulnerable to a host of bad actors, including malicious hackers, cyberthieves, and terrorists.

“The thrust of the report is that as technology develops, government will have many more tools available to find the bad guys,” says HLS Professor Jack Goldsmith, a national security and terrorism expert who was part of the group. “But it’s also true that the bad guys will have many more tools to evade the government.”

For now, he says, it’s unclear who’s going to come out ahead.

Apple v. the FBI

Of course, this rapidly expanding compendium of potential information via the IoT is “small solace to a prosecutor holding both a warrant and an iPhone with a password that can’t be readily cracked,” as Zittrain puts it, which was precisely the case in the Apple-FBI showdown.

Apple itself couldn’t access the data in end-to-end encrypted iPhones (most modern iPhones are encrypted, by default) and insisted it should not be forced to write a software program to assist in bypassing the passcode on the iPhone used by Syed Rizwan Farook when he and his wife killed 14 people in San Bernardino. Apple argued—with many Silicon Valley companies in strong support—that a court order to do so would set a disturbing precedent of “backdoor access” that would leave it vulnerable to a rash of similar requests, including from foreign governments, placing the privacy—and in the case of political dissidents, the personal safety—of all iPhone users in jeopardy.

“This is big stuff; this is dramatic stuff. I have never seen a company—a Fortune 500 company, let alone one of the five biggest companies on earth—take on the government this way,” including with a lengthy letter defending Apple’s position by CEO Tim Cook posted on the company’s website, says Vivek Krishnamurthy, a clinical instructor at Berkman’s Cyberlaw Clinic. Stakeholders around the world have been watching with deep interest (see sidebar).

Even before the FBI cracked the code, counterterrorism expert Olsen and many others in law enforcement agreed it was essential for the FBI to access the data on that particular phone. “There’s every reason to think that the cellphone Farook used could contain critical information and evidence,” he said, in an interview before the code was cracked. “There’s still a lot we don’t know about the attack. Was it directed by ISIS or some other terrorist group? Were the shooters part of a cell? Are there others planning additional attacks? There are lots of important questions the FBI is responsible for answering.”

The government had a strong position because the circumstances of the case were so compelling, and because it “did everything right” by obtaining a warrant and also trying to access the data without Apple’s assistance before turning to the court to compel Apple’s help, Olsen argued. Moreover, the request was narrowly tailored to one phone, he added, the property of Farook’s employer, which had consented to disabling the security feature.

But Schneier argues that our national security is better protected by strong encryption despite the difficulties it presents to law enforcement. “If a back door exists, then anyone can exploit it,” Schneier wrote in a New York Times blog. “That means that if the FBI can eavesdrop on your conversations or get into your computers without your consent, so can cybercriminals. So can the Chinese. So can terrorists.”

“Encryption makes it harder for the government to do its job—that’s indisputable,” says Jennifer Daskal ’01, former senior counterterrorism counsel at Human Rights Watch who now teaches at American University Washington College of Law. “But is the increased ease of government access worth the security costs that would result from a government-mandated back door? I don’t think it is.” The new Berkman report, she adds, “points to a whole host of other potential ways for the government to access sought-after information. Some may be more costly or time-consuming for the government, but they are much preferable to the kind of insecurities—as well as costs to American businesses—that would result from mandatory back doors.”

Matt Perault ’08 is head of global policy development at Facebook. While Facebook recognizes that law enforcement has an important role in fighting “legitimate threats to public safety,” the company “will fight aggressively against requirements for companies to weaken the security of their systems,” he says. “We can’t make it easier for law enforcement to access encrypted communications without making it easier for cybercriminals and foreign governments to do the same.”

Zittrain points out that a larger battle looms between companies like Apple and law enforcement organizations such as the FBI. “Apple is in a position to make a new generation of phones that even Apple can’t crack,” he says. “At that point, the tension between law enforcement and industry will shift from a one-off demand for assistance through judicial action to the U.S. Congress, which might be asked to mandate how companies build their products and services.”

Ultimately, it is up to Congress to resolve the issue, Goldsmith says: “The balance must be struck by Congress because there will not be agreement on the costs and benefits, and in a democracy, that’s for Congress to sort out.” While he predicts that Congress ultimately will force tech companies to give government the tools it needs for criminal investigations, he doesn’t see it happening any time soon, given the political paralysis in Washington, D.C.

Without regulation, there’s a risk the Internet of Things “will become the Wild West of the Internet.”

Meanwhile, the Internet of Things is raising “new and difficult questions about privacy over the long term,” according to Zittrain, yet is mushrooming with almost no legislative or regulatory oversight. We are, he says, “hurtling toward a world in which a truly staggering amount of data will be only a warrant or a subpoena away, and in many jurisdictions, even that gap need not be traversed.” The law—notoriously slow in responding to technological changes—may be facing one of its biggest challenges yet.

“While a number of federal agencies have flagged the IoT as being problematic for both privacy and security reasons,” says O’Brien, “little has happened,” which demonstrates not only a lack of coordination among various arms of the government but also uncertainty about competing policy interests between innovation and consumer protectionism. A strict regulatory regime could hamper this growing part of the economy, but on the other hand, without regulation, “there’s a risk the IoT will become the Wild West of the Internet,” he says, adding, “Some might argue we’re already headed in that direction.”

“It’s a wake-up call that we really should be thinking about building in certain protections now for the Internet of Things,” says Zittrain, who wants academia, governments and industry to focus on developing an Internet of Things “Bill of Rights.”

“That’s why this report and the deliberations behind it are genuinely only a beginning, and there’s much more work to do before the future is upon us.”