Theresa Champ LL.M. ’26 knows her life story — and her journey to becoming a leading Navy lawyer — is unconventional, to say the least.

For starters, how many other service members were blacklisted from the Eastern Bloc — as a child?

Today, Champ, most recently the top Judge Advocate General for the Navy’s Sixth Fleet, is celebrating 17 years of service and attending Harvard Law School’s Graduate Program. But growing up, a career in the armed forces seemed quite unlikely.

Champ is the youngest of five children born to counterculture Christian parents who, like many of their generation, maintained a distrust of the government shaped by the Vietnam War and the turmoil of midcentury America.

“I’m probably the last person you would expect to end up in the military,” Champ laughs.

By the time Champ was born, her family was living in Texas, traveling between the Lone Star State and Mexico, where they brought humanitarian aid to orphanages and homes for the elderly while sharing their religious faith.

When she was 5, Champ’s family moved to Eastern Europe, settling primarily in Budapest. There they continued their mission, hoping to convert communists to Christianity. Despite the challenges of life behind the Iron Curtain, these were some of Champ’s happiest years growing up. “Hungary is a beautiful country and there are a lot of great people there,” she says.

On one particularly memorable road trip, the family traveled in their camper van from Budapest into Moscow. “It was a surreal experience being in the Soviet Union in particular during that time, because we had to always be on guard,” she says.

Champ and her family arrived at the USSR border in the middle of the night, where the van was searched by soldiers hunting for contraband.

“They tore the motor home apart, but they didn’t find anything,” she says. “All the while, us kids had smuggled these religious tracts in our clothes and a special bodysuit my mom was wearing.”

Later, while living in Bulgaria, Champ’s mom met a group of young people who seemed friendly and interested in their message. They turned out to be KGB agents. “We ended up getting kicked out of the country and blacklisted from all the Soviet Bloc nations,” she recalls.

Feeling stifled, the family relocated once more, this time to South America, where they built schools and conducted outreach work. But Champ’s patience with that life was running thin, and at age 15, she told her parents she was done. She wanted to go back to the U.S. and become a lawyer.

“I didn’t know what that meant,” she says. “I had just gotten it in my head from watching the movie ‘Beaches.’”

Eventually, Champ made her way to Oregon, where a few of her older siblings had settled. She began taking community college classes, her first real structured education — and fell in love with learning. “I had never really had any kind of rigor to my education, but I liked everything about it immediately. I threw all my energy into it.”

“I never thought a kid with my background could end up in the most elite law school of the nation … I’m really honored to get this opportunity.”

Champ attended the University of Oregon’s honors college, where she excelled, majoring in political science and dabbling in history, literature, and other liberal arts. When she wrote her senior thesis paper on Guantanamo Bay, she could never have imagined that she would one day go there — and even represent a few of its detainees.

After law school at the University of Washington, Champ faced a fresh dilemma: where to take the bar exam. To Champ, who had spent her childhood traveling the world freely, being tied to just one state — or having to take another test if she moved — felt daunting.

“I wasn’t used to feeling trapped by something like that,” she says.

On a whim, she met with a representative from the Navy Judge Advocate General Corps, also known as JAG. “Again, I grew up having a distrust of the military and of the government, so I thought, ‘I’m going to ask hard questions, and if they lie to me, I’m done.’”

Instead, the officer was honest about the challenges a career in the Navy would entail, she says. It would be difficult. It might require relocations and deployments. The stakes would be high.

But Champ would also have an opportunity to do meaningful work in a variety of practice areas. And she would only have to take one bar exam.

“It seemed like a positive way to continue the legacy of service from my childhood, but in a very different way,” she says. “One that was not using religion, but public service, to do something for the good of the nation.”

In the Navy

Champ’s first role out of law school landed her in Newport, Rhode Island, where she provided legal assistance to servicemembers in a variety of areas, including landlord-tenant disputes, child support and family law, and estate planning. She also represented members of the Navy, Marines, and Coast Guard who were facing administrative discharge or were being criminally charged by the military.

“Doing that job taught me a lot about the military and all the different scenarios people got themselves into,” she says.

Her next job taught her even more. Hoping to move to Washington, D.C., Champ had asked for an assignment in the nation’s capital. Of the available jobs, one seemed particularly interesting — and concerning. It involved serving as lead military defense counsel for two Guantanamo Bay detainees.

“I was intrigued by it, because I’d written my thesis on Gitmo,” she says.

Her clients — one from Afghanistan, the other from Saudi Arabia — had both been accused of terrorism, but their cases had stalled for years. Early in his first term, President Barack Obama ’91 had promised to close the prison, but there was uncertainty as to what would happen to detainees if it did, she says.

The work there was difficult and sensitive, but Champ eventually obtained a plea deal for her Saudi client — the first movement that had occurred in any Gitmo case in years, she says. “I learned a lot from that assignment, and I certainly felt like we were doing something historic.”

But by then, Champ knew she wanted a role that was more directly tied to the Navy’s daily operations. “I felt like I had been on the fringe,” she explains.

So, she accepted a job as deputy general counsel for the one-star general leading the Naval District Washington in the nation’s capital and was soon promoted to lieutenant commander. A few years later, she returned to her adopted state of Washington to lead the Navy’s legal services department in the Northwest.

Then, in 2018, Champ received a life-changing phone call. How would she like to serve on a ship that was about to deploy around the world?

“I was nervous, but I said yes,” she says. “After all, that’s why I joined the Navy.”

As general counsel to the commanding officer of the nuclear aircraft carrier U.S.S. John C. Stennis, Champ circumnavigated the globe while advising on matters both domestic and international, including negotiating the release of U.S. sailors who had gotten in trouble with local authorities during port visits in Singapore and Thailand.

As that seven-month deployment was ending, the COVID pandemic was just getting started. Champ switched gears taking a job of managing the placements of the Navy’s 500 JAG Corps lieutenants. “This was no easy task, and one I was very keen on getting right, because I understood that this was the business of people’s lives.”

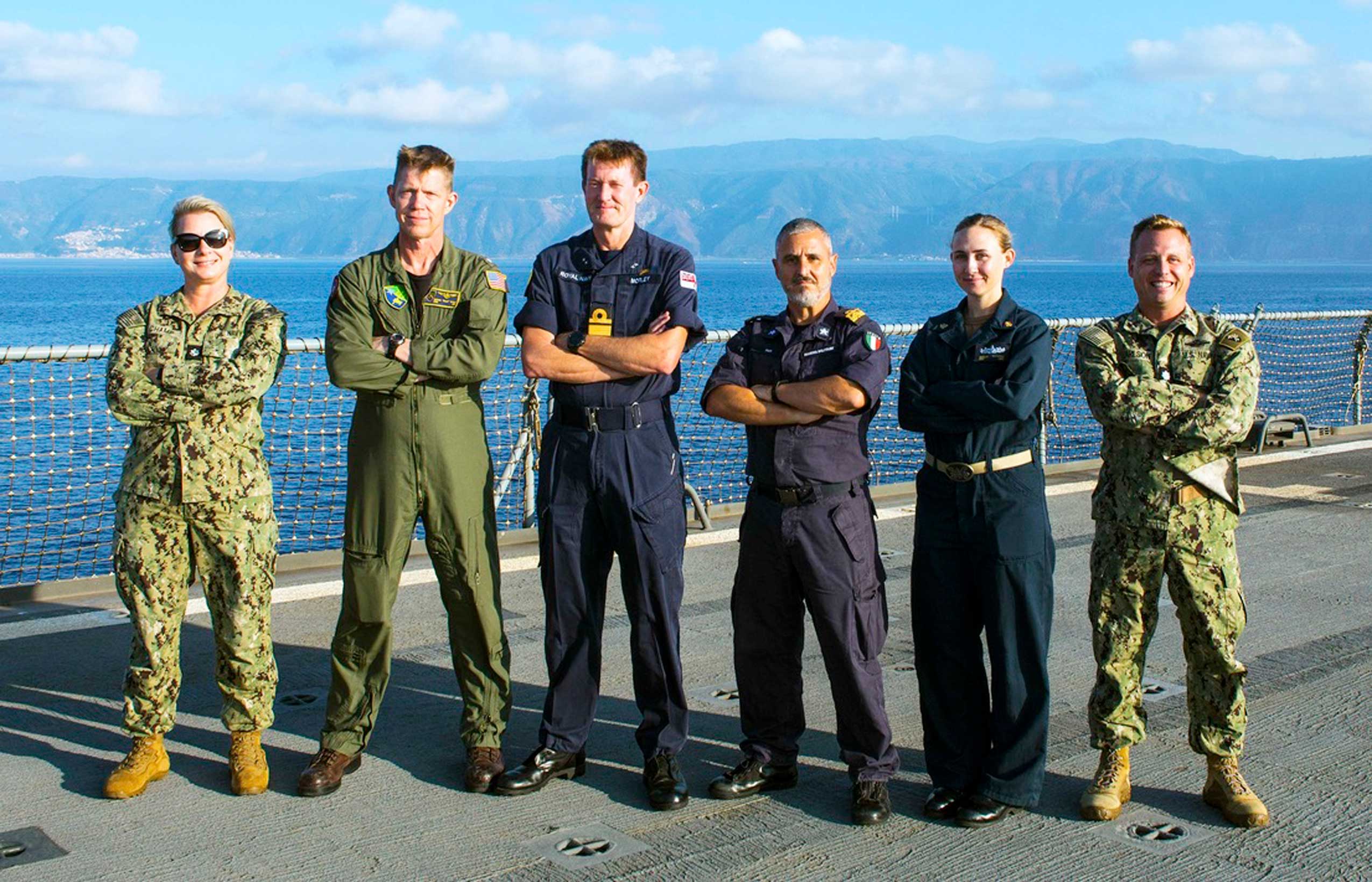

From there, Champ went to Naples, Italy, to serve as the chief of operational and international law and then as the primary JAG for the Navy’s Sixth Fleet — the maritime forces covering all of Europe, the Mediterranean, and parts of Africa.

There was no shortage of work. Her first job was helping to support Ukraine during Russia’s full-scale invasion, always within the bounds of international and domestic law, she says. “We didn’t want to become cobelligerents,” she says.

After Hamas’s attack on Israel in October 2023, Champ was assigned as the primary legal advisor to the 3-star admiral on the Navy’s Sixth Fleet flagship, the U.S.S. Mount Whitney. The mission evolved from planning evacuations of American citizens from the region to providing maritime security for humanitarian aid into Gaza, and assisting in the defense of Israel from Iranian threats.

“We were very, very busy, but it was an incredible experience, and I learned so much,” she says.

‘Grateful for the opportunity’

Last year, when the Navy offered Champ the chance to further her education as a graduate student at Harvard Law School, she was ecstatic. Now in her 17th year of service, Champ sees studying at Harvard as yet another unexpected detail in the unique story of her life.

“I never thought a kid with my background could end up in the most elite law school of the nation,” she says. “I’m really honored to get this opportunity.”

Champ’s favorite course so far is Law in Global Affairs, taught by Professor David Kennedy ’80, which she says has challenged her to think in new ways about the law and its impact on world events. “It has been very interesting to hear different perspectives on some of the issues that I deal with in my career.”

She adds that she is learning from everyone she meets, from the faculty to the students, who hail from the U.S. and all over the world. “I could not be more impressed with everyone here,” she says.

In May, following graduation, Champ will deploy to Jordan, in the Middle East, to work with special forces there. For now, she says she appreciates having the time to proactively dive into the tangled web of international and domestic laws that govern her work — which will ultimately help her advise military leaders as they devise and execute tactics and strategies.

“I’m grateful for this opportunity to really think things through and process them,” she says. “I believe it’s going to give me the skills and the ability to perform better while I’m deployed.”

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.