Charlie Munger gave up law to pursue his fortunes as an investor. Jim Cramer never even tried to be a lawyer, and went straight to Wall Street. Jim Donovan and Todd Buchholz saw law school as an imperative step on the road to a successful business career. Sean Healey, who once dreamed of teaching law, discovered his place was in the investment world instead.

But these five HLS alumni would never say they abandoned their legal training. They just redirected it toward the place they each found more alluring: the world of high finance.

Today, they have nearly 100 years of combined experience in investing and business, and have been responsible for billions of dollars in assets. Each is wealthy in his own right and has, directly or indirectly, helped others to become quite comfortable too. And while each is at a different place in his career–one is more than half a century out of HLS, another not even ten years–all share an appetite for taking big risks for big gains. Yet, they also possess the coolheaded confidence that is essential when millions are at stake on a regular basis and market fluctuations send shivers down Wall Street.

Investment Values

The cultish devotion of Berkshire Hathaway shareholders is legendary in the financial world. After all, more than a few people have become independently wealthy as a result of the investing genius of CEO Warren Buffett.

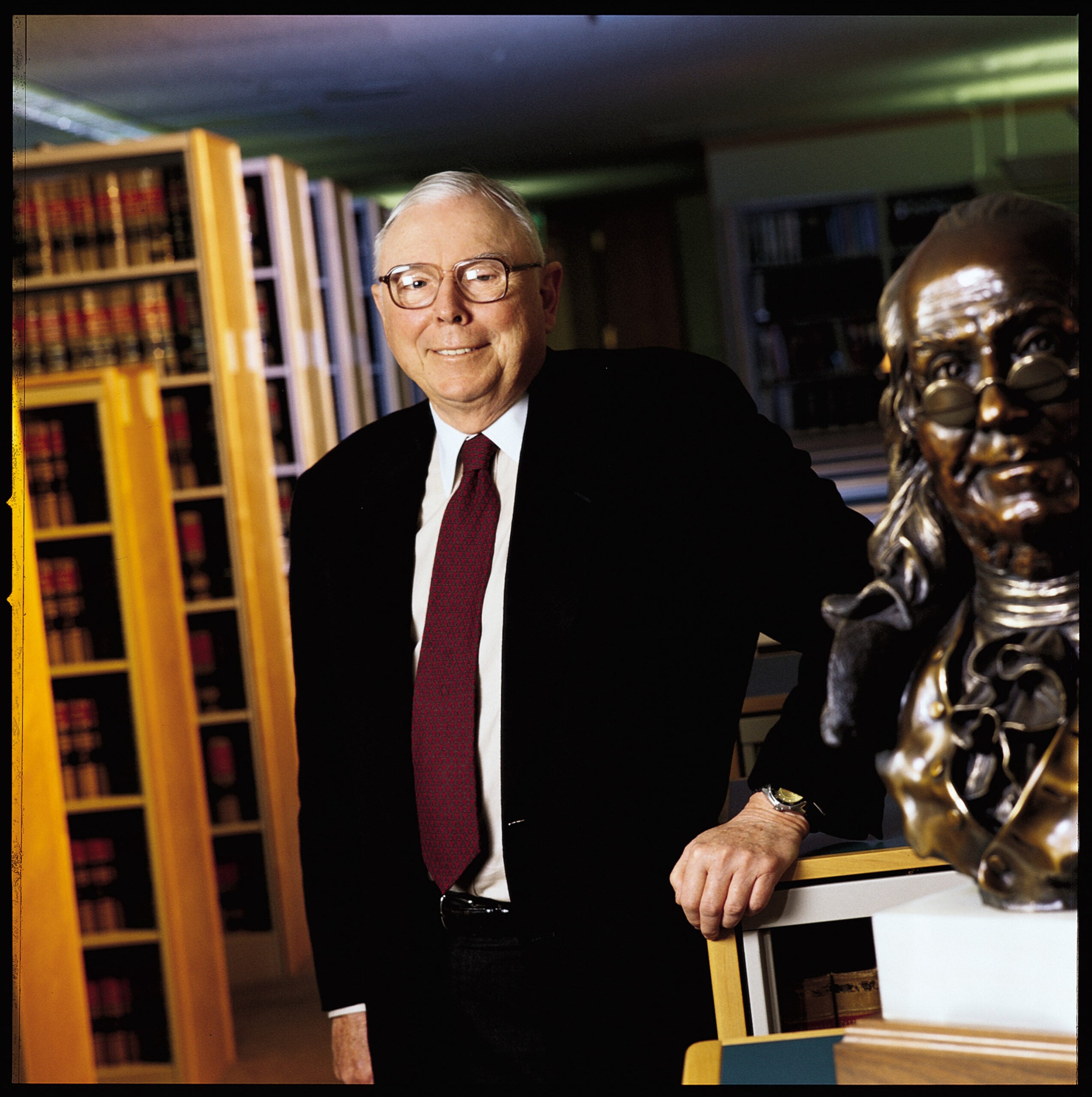

But while Buffett’s name alone has long been synonymous with Berkshire Hathaway, there is one person in the company even he looks up to: his partner and old friend from Omaha, Charlie Munger ’48.

“I call myself the assistant cult leader,” joked Munger.

The pair has had a prosperous partnership–spanning four decades–and they’ve done more together than just build a holding company worth billions. They have been stalwarts of ethical business practices, have rooted out fraud, and have even championed abortion rights and the establishment of Planned Parenthood.

Primarily involved in property and casualty insurance, Berkshire Hathaway has smaller holdings in publishing, candy, footwear, and furniture. By the end of 2000, its revenues had ncreased to $34 billion, its profits to almost $3 billion. Shares in Berkshire, just $12 each in 1965, hit $71,000 by year’s end.

Munger, who is Berkshire’s vice chairman, now finds himself a very wealthy man. A voracious reader and devotee of great thinkers like Ben Franklin and Samuel Johnson, he credits their wisdom for his success. “They were both utterly brilliant men. And powerful communicators. Both have helped me all the way through life. Their lessons are easy to assimilate.”

Berkshire has its own interesting lessons for the world, he says, and they come from the company’s high standard of ethics and its bottom-line achievements.

“I’m proud to be associated with the value system at Berkshire Hathaway,” Munger said. “I think you’ll make more money in the end with good ethics than bad. Even though there are some people who do very well, like Marc Rich–who plainly has never had any decent ethics, or seldom anyway. But in the end, Warren Buffett has done better than Marc Rich–in money–not just in reputation.”

Even so, Munger does not pretend that what he and Buffett have accomplished is just a matter of being good guys. It also takes sharp wits, strategy, and a lot of discipline. Still, Munger contends that more people could do well in investing than actually do, if they’d employ some of the basic “mental methods” he and Buffett have used.

“The number one idea,” he said, “is to view a stock as an ownership of the business [and] to judge the staying quality of the business in terms of its competitive advantage. Look for more value in terms of discounted future cash flow than you’re paying for. Move only when you have an advantage. It’s very basic. You have to understand the odds and have the discipline to bet only when the odds are in your favor.”

And Berkshire, he says, is not in the business of making money by calling macroeconomic swings. “We just keep our heads down and handle the headwinds and tailwinds as best we can, and take the result after a period of years.”

At 77, Munger is busier than ever. Aside from his work with Buffett, he is chairman of the L.A.-based legal publisher the Daily Journal Corporation and CEO of Wesco Financial Co., a subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway. He has a large family and spends a great deal of time with his wife, children, and grandchildren. He’s also a long-standing philanthropist who has bolstered education and health care causes in Los Angeles, where he has lived for five decades.

Munger quit practicing law in 1965 after 17 years, because “sometimes you’re on the wrong side. Often you’re dealing with unreasonable people where you can’t fix things fast. It’s inefficient. I like the discipline of backing my own judgments with my own money. It suits my temperament better. Of course, I also realized that the upper potentialities were better outside of law.”

Now a billionaire, Munger seems somewhat surprised by just how successful he has been in his life. When he graduated from HLS, Munger said, “Practically nobody expected to be rich, or had any examples that would lead him to expect to be rich. That has totally changed. We’ve had the most massive creation of wealth for people a lot younger than those who formerly got wealth in the history of the world. The world is full of young people who really want to get rich, and in those days nobody thought it was a reasonable possibility.”

Balance Sheet

It’s a Monday in March, the day the NASDAQ slipped under 2,000 for the first time in almost two years. Jim Cramer ’84 is filing one down-on-tech commentary after another for TheStreet.com, the investing site he launched in 1995 with former HLS lecturer Martin Peretz. He usually files six or seven columns a day on the investing how-to site, but this day, he’ll post ten missives, most of them skewering investors and individual companies for placing far too much faith in the technology sector.

The famously bombastic former Wall Street trader–he gave it up in late 2000–had been criticized for being bearish on tech. But, as the NASDAQ withered and the business press called for his opinion, Cramer felt vindicated.

“I think tech is awful,” he said. “People don’t listen. Technology–the industry–is a growth industry. But tech stocks may be overvalued. I’m a huge bull in the stock market, but I can’t be a bull in that sector.”

Many people do listen to Cramer. He made millions for investors over the nearly 20 years he spent trading, first from his dorm at HLS and later from his own hedge fund, Cramer, Berkowitz & Co.

Cramer loves the stock market. And it has suited him well. His acumen for numbers is legendary; he can recall every trade he made in a day or even in a year. At HLS, he followed the market’s every move from his room, and made enough from trading to cover tuition. He even recorded his weekly stock picks on his telephone answering machine and got his first investment client when Peretz–who made money from those picks–enlisted Cramer to manage his money for him. When Cramer tripled his earnings, the two formed a partnership that remains strong today.

Cramer says once he got the fever for the stock market, he couldn’t see himself working as an attorney but worried that he might disappoint his family. He credits Dean Robert Clark ’72, a professor at the time, with encouraging him to take his chances in the business world.

“I went to him and said, ‘I really love the stock market and I have a chance to work at Goldman Sachs,’ and he said, ‘I think you should do it. Follow your heart.’ I don’t think I would have done it if he had said not to,” Cramer recalled. “I met these unbelievable professors who just helped me a tremendous amount in making important decisions. I couldn’t have made it without them. If I got that out of my tuition, I did pretty well.”

Now 46, Cramer writes columns for TheStreet.com and New York magazine. His retirement from the hedge fund, he said, has been “a godsend.”

“I love my new life,” he said. “Now I just think. I’m having a great time.”

Until last December, Cramer was widely known as the manic millionaire trader who routinely got to the office by 5 a.m. He’d read five newspapers before trading opened and spend the rest of the day in a frenzy of high-stakes buying and selling. “I was really good at it,” he said. “Like a professional baseball player who had a really good batting average.”

He also garnered more than his share of controversy by writing about the stock market while actively investing and trading. He’s been accused of crossing the line into conflict of interest. But Cramer never pretended he wasn’t an interested party and has always disclosed his own stake in anything he has reported.

Cramer says he made piles of money for himself and his clients. But it took a toll on his family life. “I lived and breathed it. But I still came to work every day nervous about how I’d do. It’s one reason I wanted to give it up. It was just a very nerve-wracking job. I wanted more time with my family and for my writing. I didn’t want that pressure anymore. I had made enough money.”

The last straw, he says, came one day in November, when a trade didn’t go well. “At the end of the day, I did a trade and lost $13,000 in a few minutes,” he said. “I broke my terminal and my keyboards. I was just furious and throwing things, and my head trader and my partner said, ‘You can’t keep doing this.’ My wife was saying it, my dad, my kids. Everybody wanted me out of the business except me. I was just making everybody’s life miserable.”

In his new life, Cramer is still addicted to the morning papers, but he does sleep more. He’s at TheStreet.com offices by a healthy 7:15 a.m. and works out an hour a day. He has planned a rather leisurely summer. He manages nobody’s money except his own in what he calls “very low-impact, long-term investing stuff.”

Cramer is writing a book, expected in bookstores in September, called Confessions of The Street Addict about his Wall Street exploits and his experience running a dot-com and a hedge fund. Also in the works are a radio program called “Real Money Talk” and a regular commentary on CNBC. “I want to tell people how I made money in the market and try to keep them in the game,” he said.

Through his columns and commentary, Cramer challenges investors to understand what is happening in the markets and take responsibility for their own outcomes. Regardless of whether people have the help of investment professionals, vigilance is necessary. “You should always worry about your own money,” he said.

As the stock market dipped this winter, Cramer stayed bullish. “Stocks ran up because we felt that the Fed would come to our rescue. But the Fed didn’t put us in these stocks that are bad. There are two stock markets–the NASDAQ, which people have way too much faith in, and the rest of the market, which, I think, people have way too little faith in. I believe the system will hold.”

Economics 101

Todd Buchholz ’86 runs a multimillion-dollar hedge fund and writes regularly on the economy for the Wall Street Journal, two outstanding credentials for a man who loves to teach people about economics and investing.

“I spend my day trying to figure out the links–connecting the dots,” said Buchholz, a former White House economic adviser and now president of Victoria Capital, a hedge fund based in Bethesda, Md.

When George W. Bush got elected, for example, Buchholz had to consider how a new president would impact world markets. “What does that mean for defense spending? For defense stocks? Does it mean Greenspan is more likely to cut interest rates–or to cut interest rates sooner? And, if Greenspan cuts interest rates, will the Bank of England follow? If the Bank of England cuts interest rates, will that help the British pound against the dollar? Will it help Airbus sell more airplanes than Boeing?”

Such reasoning is at the core of Buchholz’s everyday work with Victoria, and also a way of thinking he wants readers of his columns and three books to adopt.

“It’s a big Rubik’s cube that’s constantly changing,” he said. “When you think you’ve got it solved, suddenly, the colors switch. There’s never a final game. To my mind, it’s always interesting, always challenging, and not simply about numbers.”

Ever since he was an undergraduate economics major at Bucknell University, Buchholz has been honing his finance skills and finding new ways to teach basic economics. He enrolled at HLS, unsure of what he wanted to do. All he did know, he says, was that law school would benefit him.

“I felt that society was supported, and in some ways controlled, by an underground structure,” he said. “I thought that in order to be a successful participant in either the private sector or the public sector, it made sense to go down into the basement and figure out what that structure was–that being the legal structure. I wanted to learn to think like a lawyer and to make decisions weighing precedents against the black letter of the law and common sense. Plus, I had always enjoyed public speaking and felt legal training would be helpful with that.”

During his HLS days, Buchholz was an economics teaching fellow at Harvard College, work that earned him the Allyn Young Teaching Prize. He later studied economics at Cambridge University and wrote his first book, New Ideas from Dead Economists: An Introduction to Modern Economic Thought. In the book, Buchholz applies long-standing economic theories to modern issues, making the thoughts and writings of the great economists of the past relevant to the economic and social matters we face today.

The book led him to the White House. He had worked closely with Martin Feldstein, President Reagan’s chief economic adviser and head of the major introductory economics course at Harvard. Feldstein encouraged Buchholz to get involved in the 1988 presidential campaign. That work yielded him a job as a director of economic policy at the White House.

Working in the White House was, Buchholz said, both “exhilarating and frustrating” because George H. W. Bush had begun his term as a very popular president but was unable to sustain that popularity through the end of his term.

In addition to running Victoria Capital and contributing regularly to the Wall Street Journal, Buchholz is a contributing editor for Worth Magazine and a frequent guest on ABC’s World News Tonight. He provides monthly commentary on PBS’s Nightly Business Report and speaks to companies about the economy and corporate strategy.

Buchholz’s third book, Market Shock: Nine Economic and Social Upheavals That Will Shake Your Financial Future–and What You Can Do About Them, which describes various modern trends and how they affect financial markets, is aimed at the average investor.

“We now are a country of capitalists,” Buchholz said. “Most families own stock. Most people these days turn to the financial pages before the sports pages. We now seem to have a much greater interest in understanding the financial markets, as well as the economy. We are all now responsible for ourselves and our financial futures.”

Writing on the economy lets Buchholz continue his teaching, as he helps people understand the forces that impact their financial well-being.

“I’ve tried to figure out fresh and witty ways to explain economic, financial, and political events,” he said. “These subjects don’t have to be dull. They don’t have to be rote. I try to draw on popular culture to make these ideas more fun and accessible. There’s still a bit of a teacher in me, and I get satisfaction from being able to express ideas in ways that open people’s eyes.”

Cash Flow

When Sean Healey ’87 walked into Goldman, Sachs & Co. in New York as a summer associate before his final year at HLS, he had no idea what he was getting into.

“They didn’t have extra training for lawyers, so it was quite an eye-opening experience,” he said. “While I didn’t actually look for tellers when I first got there, it wouldn’t have shocked me if there had been some.”

But Healey, who started law school with hopes of becoming a law professor, soon found the world of finance far more fascinating than the prospects of teaching. Now he heads one of the country’s ten largest publicly traded fund companies, Affiliated Managers Group (AMG).

As president and chief operating officer at the Boston-based investment management holding company, Healey has worked alongside CEO William Nutt to take the firm from IPO to a $77.5 billion enterprise at the end of 2000, with holdings in 15 investment management firms and its own line of mutual funds.

Healey cut his financial teeth at Goldman Sachs, where he stayed for eight years after graduating from HLS. He was a vice president in mergers and acquisitions when a chance meeting with Nutt during a merger deal led to his move to AMG in 1995. The still-young AMG is growing rapidly, Healey says.

“Investment management is quite attractive as a business because it generates substantial cash flow without substantial capital expenditures–compared to law or investment banking, where you start the year at zero and have to go find your cases and find your deals. With investment management, you start with all those assets, and while clients can take them away or the market can go down, it’s still a much more stable business.”

AMG does not buy companies outright but rather buys equity stakes in them. Current holdings include Frontier Capital Management, Essex Investment Management, and Tweedy, Browne, a New York- and London-based firm that was named International Fund Manager of the Year for 2000 by Morningstar, the investment rating service.

According to Healey, AMG has done well because the investment management industry as a whole has been growing rapidly and shows no signs of slowing down.

“People who once had their money in a CD at a bank are now investing it directly in the stock market,” he said. “And it’s broadly agreed that professional investment management can add value–that investing is not something that people necessarily have the time or expertise to do on their own.”

Healey says about one-quarter of AMG’s earnings comes from investments in global securities and 92 percent of earnings comes from investments in equity securities. The company also has hedge fund assets totaling $3 billion and is looking to invest in firms that are exclusively focused on hedge funds.

Healey spends much of his time meeting prospective new affiliates, meeting with shareholders, and dealing with financing sources. “Our particular approach to the business is interesting because I’m regularly interacting with entrepreneurs who have built their own firm in their own way and who have achieved a lot of success. It’s quite a fascinating group.”

While sharp movements in the markets are always a concern, Healey says AMG’s diversified collection of firms helps keep it fairly stable.

“Last year, the market went down and our earnings continued to rise,” he said.

Indeed, even as the economy began to flag early this year, Healey was not terribly concerned.

“I don’t have an informed opinion on whether there will be a recession,” he said. “I think what it means for investors is that a long-term orientation is required. Inevitably, people who try to time the market in the short term are disappointed. Think long term and diversify. Don’t pick too many advisers. Pick someone or some entity that you’re comfortable with. What’s right for one investor won’t work well for someone else.”

Liquid Assets

Not only can Jim Donovan ’93 help you decide how best to fund your child’s education, he can even help you select the school. If you want to start a company or buy a house, go ahead and call him. Just make sure you’ve got at least $25 million in liquid assets before you pick up the phone.

“When you have that much money, you’re in a league where you really should have access to the best performance and service,” said Donovan, a partner at Goldman Sachs and managing director of its Private Wealth Management Group in Boston. It’s Donovan’s job to take care of every financial whim of New England’s wealthiest families, from identifying philanthropic opportunities, to buying and selling companies, and everything in between. And he is busier than ever.

Wealth management, he said, “has been growing dramatically over the last ten years or so.” The fact that multimillionaires rely on him to manage their huge assets doesn’t seem to faze the 34-year-old Donovan. While he is a direct adviser, he knows he’s not alone.

“I’m not directly responsible; Goldman Sachs is responsible,” he said. “I’m really just a liaison. I find out what is most important to the client and then bring to bear the resources of Goldman Sachs. We have roughly 20,000 people worldwide who are experts in commodities, foreign currencies, private/public investing, fixed-income equities. It’s comforting to know you have the firm behind you like that.”

Still, a good deal of confidence, along with a good head for numbers, is essential in this burgeoning business, and Donovan has both in abundance.

A native of Danvers, Mass., Donovan says his high aptitude for math and science led him to MIT to study chemical engineering. He became a star athlete as a rower on MIT’s Division I crew team. Always pushing himself to excel, he applied and was accepted in his junior year to an exclusive program that allowed him to pursue his MBA at the Sloan School of Management while working on his bachelor’s degree. He finished both in five years.

Donovan had always intended to pursue a business career and felt a law degree as well as a business degree would be invaluable. Mentors he met during summers spent working at an investment bank, at a law firm, and as a White House Fellow only confirmed that belief.

When he finished law school, Donovan knew he’d go into business, either as an entrepreneur or as an investment banker. So when the offer came in from Goldman Sachs, he couldn’t turn it down.

Now he advises a “very diverse group of people” on what to do with their millions. That variety–in his clients’ personalities, circumstances, and attitudes–is what makes his job fun.

“They’re very interesting people,” he said. “They’re entrepreneurs, scientists, academics, politicians, people who have inherited wealth, widows, widowers, celebrities. The common theme is they’re all wealthy and want terrific service and results.”

Those clients are also sophisticated about the foibles of the market. “Our approach is very long term,” said Donovan. “We do not panic and tend not to have clients that panic.”

Now a recruiter for Goldman Sachs, Donovan returns to HLS each year to urge students to consider a career in finance. It is not a digression from the rigorous training they’ve received, he says.

“First, [a law degree] is a great credential,” he said. “Second, you learn a lot about tax and trusts and estates, and third is the approach. The logical approach that you learn in law school for solving problems is very helpful.”

The statistics bear this out, as a steady flow of HLS graduates each year goes straight to Goldman Sachs and other finance and management firms. “But I still worry that too many [students] at law schools, including Harvard, don’t look at all their options. They’re just assuming they have to practice law and they don’t look at finance.”