In 2007, U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, writing for the slim 5-4 majority in Massachusetts v. EPA, began the Court’s 32-page opinion with a deceptively simple premise: “A well-documented rise in global temperatures has coincided with a significant increase in the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Respected scientists believe the two trends are related.”

These two sentences, reflecting the scientific consensus that climate change is both real and related to the emission of greenhouse gases, were hardly noteworthy from a climate science perspective. But they formed the opening to a legal and political bombshell, the most important environmental law case ever decided by the Supreme Court.

At issue was whether the government of the United States—the world’s greatest air polluter for decades—had the legal authority to even address climate change, the key environmental issue of our time. The decade-long, behind-the-scenes tale of how the Court came to the legally unprecedented conclusions that states could sue the federal government to enforce climate change regulation, and that the Environmental Protection Agency has the authority, and perhaps the mandate, to regulate greenhouse gases, is the subject of a new book by Harvard Law School Professor Richard J. Lazarus ’79, “The Rule of Five: Making Climate History at the Supreme Court.”

“Ostensibly about one specific environmental law case, ‘The Rule of Five’ is a love letter to Supreme Court advocacy more broadly.”

The book marries Lazarus’ two main areas of scholarship: environmental law and Supreme Court practice. Ostensibly about one specific environmental law case, “The Rule of Five” is a love letter to Supreme Court advocacy more broadly. In it, Lazarus traces in painstaking detail the countless emails, conference calls, drafts of briefs and opinions, hours of oral argument preparation, and even secretive Supreme Court negotiations that ultimately turn a distinct legal dispute into a case that thousands of law students now study in classes on environmental, administrative, and constitutional law.

Lazarus set out to “write a book for a popular audience that made the challenges, the strategies, the dynamics of Supreme Court advocacy and what the Court does come to life.” To accomplish that goal, he took to heart the advice offered by HLS Professor Mark Tushnet, who warned him that to be of interest to nonlawyers, the book ultimately had to be about people.

And so Lazarus framed his story around the arc of one lawyer: Joe Mendelson, a young, upstart public interest attorney who in 1999 worked for an unknown environmental organization consisting of five attorneys occupying a small suite of rooms in Washington, D.C. Mendelson, against the advice of nearly every major environmental group in the country, filed a petition with the EPA to force its hand to address climate change.

The book captures how that petition caught the attention of the top ranks of the Bush administration and later landed in federal court. Years later, the environmental attorneys’ victory in the Supreme Court provided the legal authority necessary for the Obama administration to regulate greenhouse gas emissions. Those steps then directly and dramatically resulted in the 2015 Paris climate accord, in which virtually every nation pledged to cut or significantly limit new emissions. In an epilogue, however, Mendelson awakes on Nov. 9, 2016, to learn that Donald J. Trump has been elected president of the United States, threatening his hard-fought victory.

In between, “The Rule of Five” tells the story of a group of attorneys, self-dubbed the Carbon Dioxide Warriors, who changed environmental law through brilliant maneuvering and persuasive arguments that proved that “the best environmental lawyers are not the best ‘environmentalists’—they are the best ‘lawyers.’” Their tale reveals the power that one clever, committed, engaging, or indomitable personality can have to shape a legal legacy.

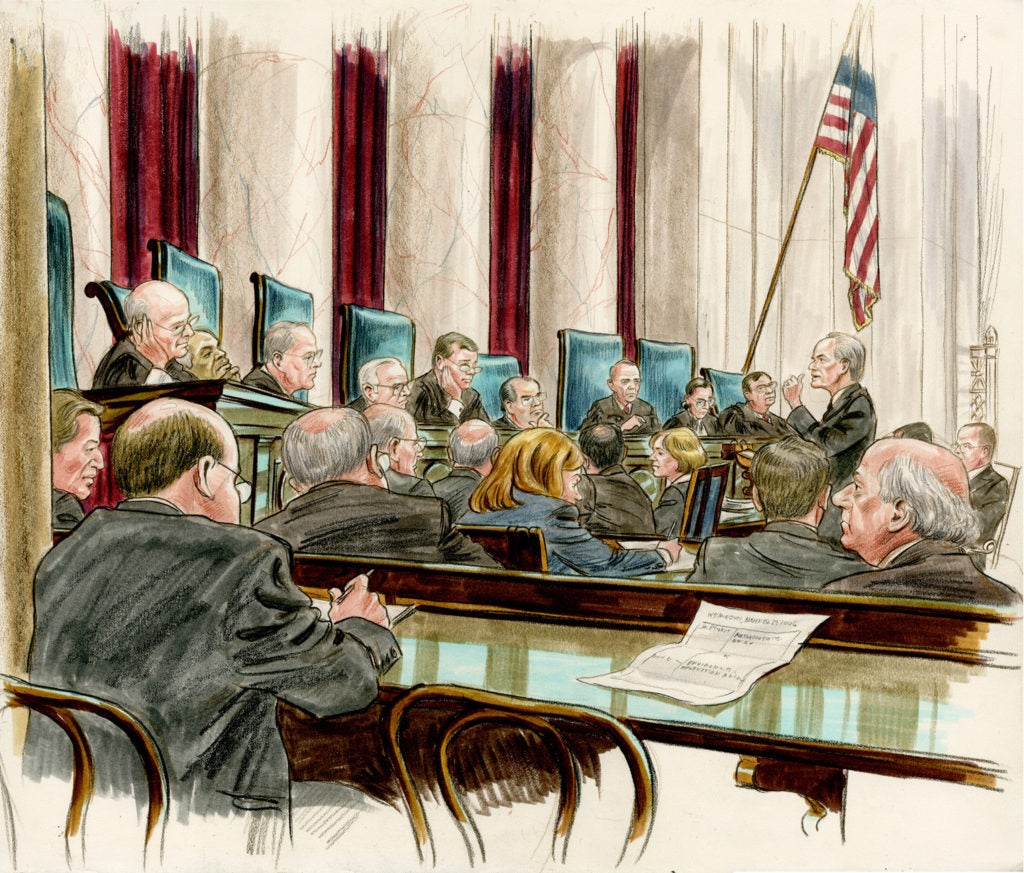

That legacy came, however, at the cost of decades of friendships amid unparalleled infighting that threatened the group’s success. By the time lead counsel Jim Milkey ’83 stood up to present the oral argument in Massachusetts, he was no longer on speaking terms with most of the legal team, including Lisa Heinzerling—the principal drafter of the brief filed with the Supreme Court—whom he had personally invited to join the legal team but who later became his chief rival for the oral argument spotlight. Conflict abounds in high-stakes litigation, Lazarus says, but it rarely lasts when the results are as spectacular as they were in Massachusetts. “You win a case, everyone sort of jumps around,” he says. “That didn’t happen here.”

Jim Milkey ’83, lead counsel in Massachusetts v. EPA, is depicted here presenting the oral argument before the Supreme Court in 2006

To uncover the details of the larger-than-life tale, Lazarus spoke to nearly every major participant in the litigation, from Mendelson, architect of the initial petition; to the Bush White House officials who vehemently opposed it; to Justice Stevens himself, who carefully drafted an opinion just narrow enough to maintain Justice Anthony Kennedy’s tenuous vote.

Facts casually revealed throughout the book belie Lazarus’ great efforts to obtain them. For instance, buried in the middle of a chapter about drafting the opening brief for the D.C. Circuit, Lazarus reveals that one member of the team quietly invited an outside expert to review the brief. That expert was retired D.C. Circuit Chief Judge Patricia Wald, who was unusually well positioned to advise the litigants. Her involvement was so little-known, however, that even the Carbon Dioxide Warriors themselves learned of it only from Lazarus’ book. Lazarus discovered Wald’s role after a student assistant asked him who had penned a comment on a particularly insightful, handwritten critique of a draft of the brief. To find out, Lazarus engaged in old-fashioned sleuthing, digging through 15-year-old notes from conference calls, tracking down minimally involved attorneys, and at one point even sending a copy of the comments to Wald’s daughter to ask if the handwriting matched her mother’s.

Lazarus, a former assistant to the solicitor general and veteran of 14 Supreme Court oral arguments, has long been focused on the inner workings of the Court and has published groundbreaking studies on the topic. But his reporting and research for “The Rule of Five” uncovered lore that even he hadn’t known. While shadowing Court staff as they prepared the courtroom for oral argument, he learned that each justice is supplied with a pewter mug on which their name is engraved, along with the names of each justice who previously held their seat. Over time, the names etched into the soft metal wear down and disappear, reminding the justices that they are part of a long history but will themselves, one day, also fade.

“The Rule of Five” brings to life a hard-fought landmark victory addressing, as Lazarus puts it, “the single most pressing environmental issue of our times.” Environmentalists view Massachusetts as their Brown v. Board of Education, the case that changed everything. But just as Brown did not end de facto school segregation, Massachusetts did not altogether prohibit the federal government from dismantling environmental protections or contributing to climate change.

The book ends by considering the legacy of Massachusetts in light of the severe environmental deregulation that followed President Trump’s election. The lesson to be drawn, according to Lazarus, is that lasting change can originate in strategic litigation, but it cannot end there. “Supreme Court decisions and big cases are necessary but not sufficient,” he says. “That’s how transformative change is made in the United States—not through one case, but through elections.”