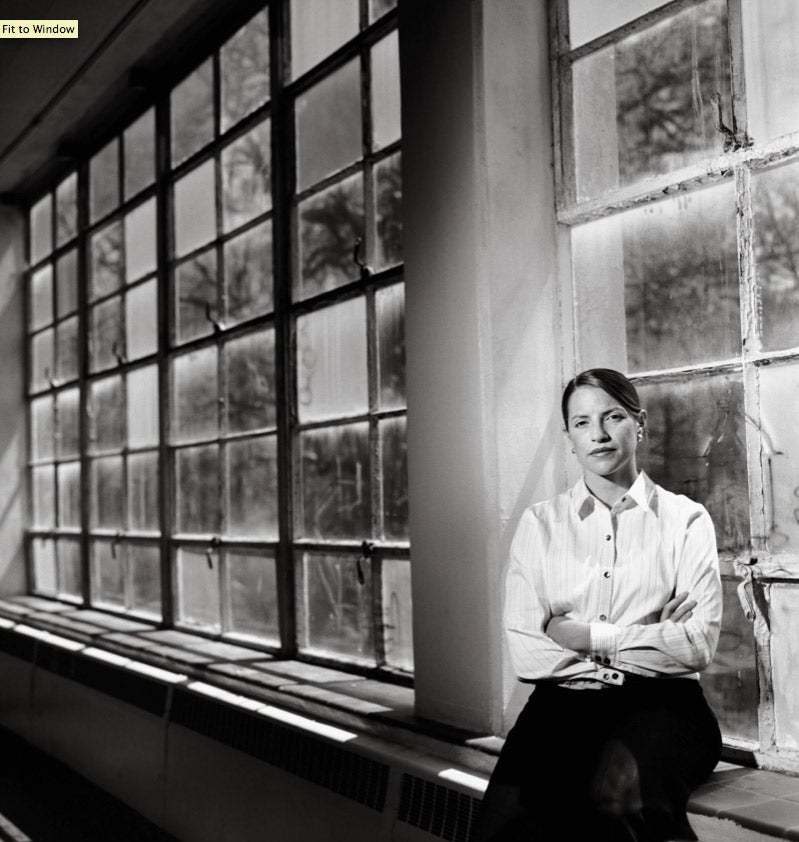

Marina Volanakis ’99 delivers on the promise of public education

Sometimes making the greatest impact on a student’s life is as simple as changing his fifth-grade homeroom. That’s what Marina Volanakis ’99 did for 10-year-old Gabriel, and it was enough to turn him from a disrespectful troublemaker into a dedicated student. And Volanakis spends most every waking hour trying to find out what will make her other students flourish too.

“I always wanted to put myself in a position where I could make real changes in people’s lives,” she said. “And we do that here every day. When I talk to parents, they tell me, ‘You’ve changed my child’s life. My child has never been so excited about learning before.'”

Last July, Volanakis founded KIPP South Fulton Academy, a charter middle school in East Point, Ga., where she serves as principal and a teacher. The school is part of the Knowledge Is Power Program, a network of charter schools that grew in 10 years from two schools in South Bronx, N.Y., and Houston to more than 30 top-performing schools in 13 states and the District of Columbia.

A typical day for the former marathoner begins at 7:30 a.m., when she leads students in a morning running program. The school day officially ends at 5 p.m., two to three hours later than most schools. It’s also open two Saturdays a month and holds a mandatory three-week session in July. Volanakis doesn’t leave work during the week until 8:30 or 9 at night, and since all teachers are on call 24 hours a day, her cell phone starts ringing at 6 p.m. with students calling for help with their two hours of required homework.

She has always believed education was the best way to change lives, but she first became passionate about public education when she taught in the Mississippi Delta as part of the Teach for America program.

“I know what we promise in terms of public education in America,” said Volanakis, “and in Mississippi I saw that the reality, particularly in low-income communities, is that we’re just not providing it. That alarmed me.”

She chose law school as a way to get involved in education reform. She interned with the Office for Civil Rights of the U.S. Department of Education during her 2L year and spent that summer at the Education Law Center of Pennsylvania. Because of the adversarial nature of the legal system, she came to feel that lawyers shouldn’t be changing schools: Educators should.

“I didn’t want to keep putting a Band-Aid on a wound that’s already there,” said Volanakis. “I wanted to find a way to make sure the injury didn’t occur in the first place.”

A former Skadden Fellow with the Atlanta Legal Aid Society, she became a Fisher Fellow in 2002 with the KIPP School Leadership Program. After six weeks learning business and operations management at the Haas School of Business at Berkeley and four months traveling around the country studying effective school models, Volanakis returned to Georgia in January 2003 to establish her own school. She visited more than 80 homes, talking with prospective students and their parents, selling her idea of a school that didn’t yet exist.

Eighty percent of her students qualify for the federal subsidized meal program, and her incoming class of 75 fifth-graders ranged in reading levels from students who were in the first percentile to one student who scored in the 99th percentile. Volanakis plans to add an additional grade each year until the academy has approximately 320 students in grades five through eight.

Some of her students’ parents were initially skeptical of what this Harvard-educated lawyer was doing setting up a school in south Fulton County. But Volanakis never wavered. She says she doesn’t wake up in the middle of the night wondering what she was put on earth to do. She knows she is doing it.