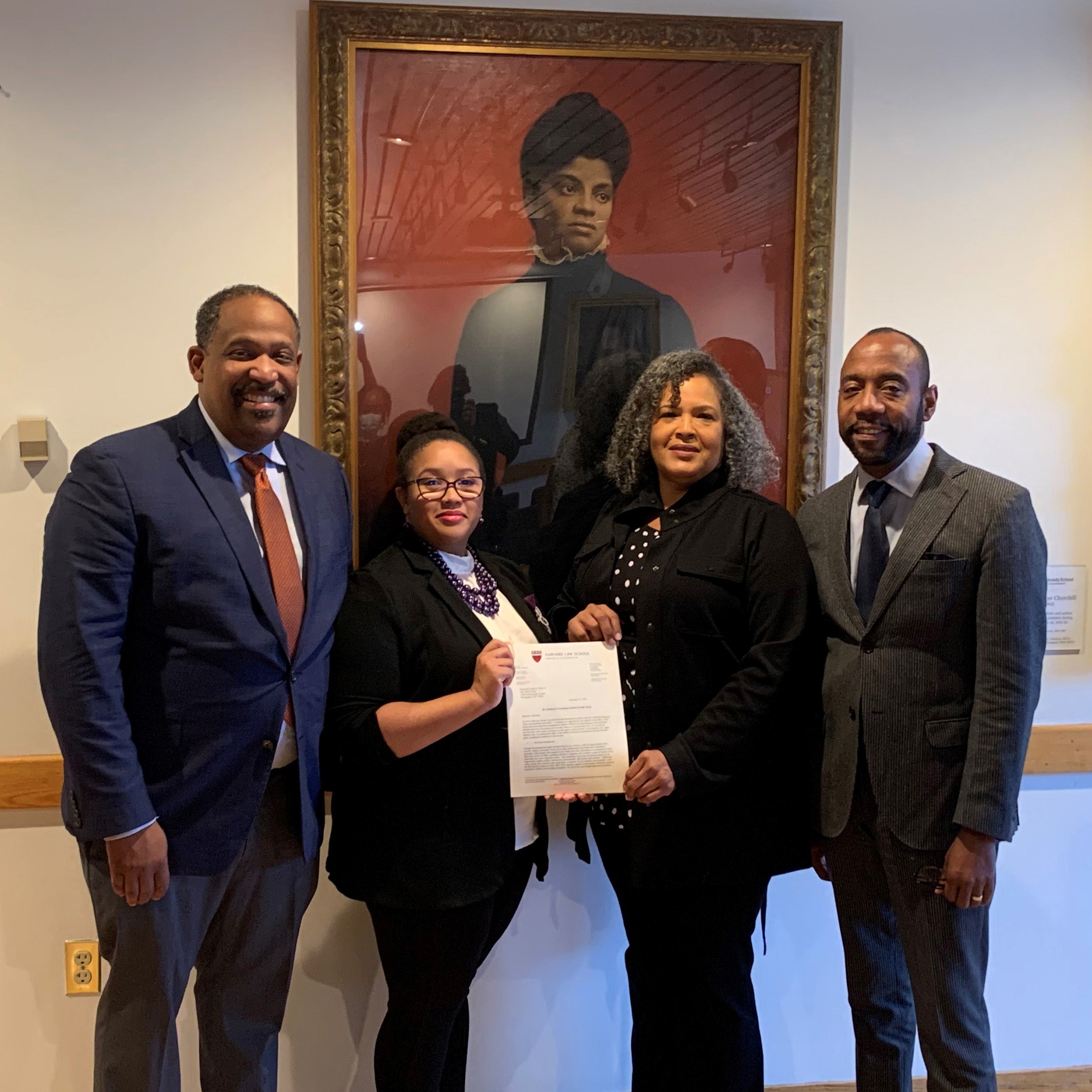

On Wednesday, Harvard Law School Professor Ronald S. Sullivan Jr. ’94, director of Harvard Law’s Criminal Justice Institute, and Harvard Kennedy School Professor Cornell William Brooks, director of The William Monroe Trotter Collaborative for Social Justice, unveiled a petition for a presidential posthumous pardon of early civil rights pioneer Callie House. The project also included a partnership with the National Congress of Black Women and the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, and advocacy by students in Brooks’ course, “Creating Justice in Real Time.”

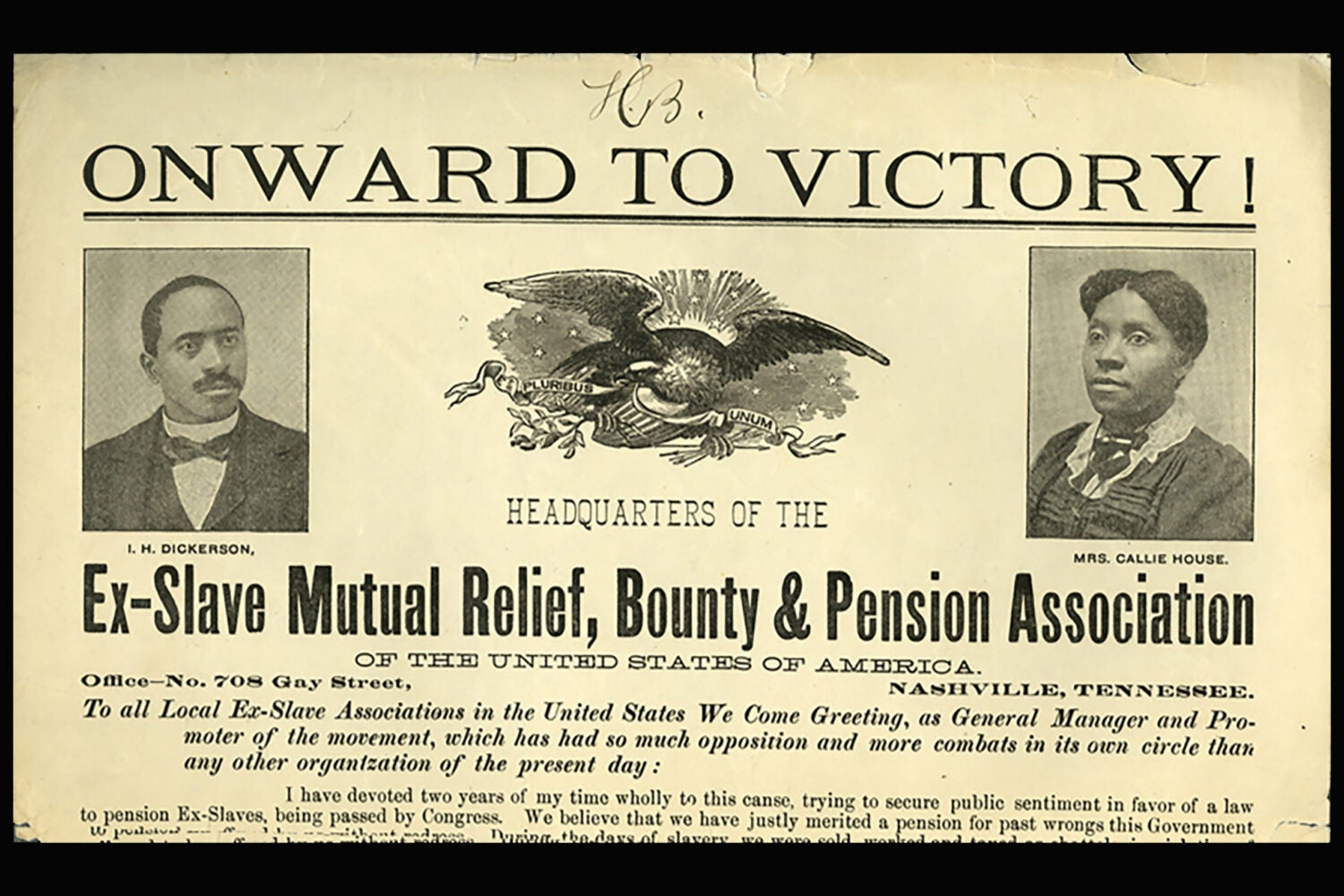

House, a formerly enslaved woman, was a leader of the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association at the turn of the 20th century. She organized hundreds of thousands of Black Americans to push for a congressional bill that would grant pensions to formerly enslaved people for their unpaid labor. House also filed an unsuccessful — but groundbreaking — class-action lawsuit for reparations for enslaved people seeking damages equal to the amount of tax that had been collected by the federal government on cotton between 1862 and 1868. As her organization grew, it and House came under the scrutiny of the U.S. government, which accused her, without evidence, of mail fraud. Eventually, the Post Office Department arrested House, and she was convicted of a felony in 1917 and sentenced to a year in prison, which effectively ended her nascent movement.

Sullivan and Brooks, who say the pardon would be an opportunity for President Joseph Biden to “right a historical wrong,” spoke with Harvard Law Today about House and her legacy, the origins of their petition, and what a pardon would mean for the U.S. and the continuing quest for justice.

Harvard Law Today: Who was Callie House? Why is it important that we know her story?

Cornell William Brooks: I think Callie House is an extraordinary figure. Well before Randall Robinson [’70], well before Bill Darity, and others who have written about reparations, we have a woman who was a widow, with five children, who was formerly enslaved, who creates a grassroots national movement, who petitions her government for reparations on behalf of elderly, formerly enslaved people. When President McKinley says this woman, this organization, is engaged in fraud, because they have the audacity to believe that they can secure compensation for elderly slaves, I would argue she was convicted of the crime of having too much hope in Congress, the conscience of this country, and the citizens. It is not a crime to believe that you can secure just compensation for people who have been harmed.

We feel fortunate and blessed to have one of the nation’s top criminal law attorneys to help us go before the president to right a historical wrong. President Biden has a number of hard and important decisions in front of him. This is an important decision that is manifestly easy.

HLT: How and when did the idea behind the petition come to be? Who worked on this effort?

Brooks: Professor Mary Frances Berry wrote a wonderful book on Callie House called “My Face is Black is True.” I read the book and was moved by this story of the foremother of the reparations movement who was unlawfully and unjustly convicted. Because I teach advocacy at the Kennedy School, I thought we could use Mrs. House as a case study to learn how to advocate for a pardon. We worked with students over the course of a semester, then reached out to Professor Sullivan and the Harvard Law School Criminal Justice Institute to help us craft a petition. We also partnered with the National Congress of Black Women and the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs — two legacy Black women’s organizations.

HLT: Why are you seeking a presidential posthumous pardon?

Ronald S. Sullivan Jr.: This is an opportunity to right a wrong. It’s an opportunity to undo an injustice. There were innumerable injustices during slavery and during Reconstruction and beyond, and there are precious few opportunities to right those wrongs. This is one — one in which the President of the United States, under Article II, Section II, paragraph one of the Constitution, has the power and authority to grant a pardon. Mrs. House suffered a real harm — jailed for a year, she and her family suffered reputational harm. This is compensatory, and a way to undo something that was manifestly unjust.

Brooks: I would footnote Professor Sullivan’s case here to say that we are seeking a pardon for Mrs. House because she suffered a wrong, but also because the movement — and America — suffered a harm. She was jailed for the better part of a year, and a movement was disrupted and ended. Our country would have benefited had that movement been allowed to grow. If we had had a reparations conversation 100 years ago, where would we be now? We would like to move the country forward in terms of the conversation about race and about reparations.

Well before Martin Luther King, well before Rosa Parks, well before Septima Poinsette Clark and so many others, Mrs. House creates this massive grassroots movement and paid for her advocacy on behalf of the country, and on behalf of elderly, formerly enslaved people, with the loss of her liberty. The record is clear that our government went after her because they wanted to disrupt her movement. Her movement was not a crime — in fact, it was a crime for the government to use its resources to stop her.

HLT: What would such a pardon mean – legally, but also morally and culturally?

Sullivan: I think it would have two related impacts. One, it would clear Callie House’s name, and do so forever. Her family and descendants will all know that her name is clear — she is no longer a convicted felon. On a broader register, it will send a message to the nation that her work was prematurely ended, and perhaps in addition, it would be a call to arms for communities to pick up that mantle and finish the work that Callie House set out to do. As Professor Brooks mentioned, the full weight of the United States government, through one of its agencies, came down on Mrs. House to stop this thing, not because it was illegal — she was 100 percent in the right — but because they were afraid of it. So, if nothing else, this petition will send the message that there is still work to be done, and that reparatory justice is not a thing of the past.

Brooks: Back in 1900, Callie House wrote to the Honorable H. Clay Evans, a pension commissioner in Washington, D.C., about the matter of whether or not she and her organization were engaged in fraud. She writes that the Constitution of the United States grants its citizens the privilege to petition Congress for the redress of grievances, and she can’t see how they would have violated the law whatsoever.

When President Biden grants this pardon, it will send a message to citizens all across this country that you have a right to petition Congress for legislation, that you have a right to assert the rights of your citizenship, and that those rights are protected under the Constitution. In other words, this petition is both retrospective and prospective – retrospective in the sense that it rights a historical wrong, but prospective in that it says to students today that you have a right to advocate for just legislation.

HLT: What lessons should we take from House’s story today?

Brooks: There are people in this country who, under the most difficult of circumstances, have somehow summoned up within themselves a belief in the possibilities of the Constitution, the possibilities of the citizenry, and I dare say, the possibilities of our Congress.

Callie House is an unsung hero of American history. The first lesson is that zealous advocacy is not merely practiced by lawyers — it is practiced by citizens, driven by conscience and the possibilities of the Constitution. The second lesson is that, as Martin Luther King reminded us, ‘truth crushed to earth will rise again.’ The truth of her cause may have been crushed by history, but yet it rises in 2022. The last lesson is that her story, and those of other enslaved people and their descendants, needs to be told in the public square.

Sullivan: There is also a lesson that everyday people can make a difference. Mrs. House, with an idea, and then a small group of people, actually caught the attention of the United States government, because of the power of that idea. People nowadays can use that as a model that, with an idea, with effort, with perseverance, they can actually move the needle. People often think that an individual cannot make a difference. ‘It’s a big country, the elites are too powerful.’ Well, world history is replete with the non-elites shaking trees, making a difference in the world.

HLT: Are there others like House whom you believe also deserve a pardon?

Brooks: I do think there are others. I believe the pardon process is incredibly powerful. My class studies the pardon process at the state level, and it strikes me that it is underutilized. I’d like to see more students at the Kennedy School work with students at Harvard Law School on these types of cases.

I also want to say that if Callie House organizes hundreds of thousands of people, if she circulates petitions way before we had digital petitions and Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook, if she did all of that with what little she had, why can’t we do more with all we have?

Sullivan: There are definitely others out there. In fact, modern historians of the Civil Rights Movement have moved away from the narrative of it being a top-down story, exploring the ways in which these movements were built from the ground up. Many of those folks were jailed, many of those folks were beaten, many of those folks were killed, and history has forgotten. Professor Brooks is prescient, because this is a tool that could potentially lead to us righting more historical wrongs, and in the process, tell these wonderful stories — and not just to students at Harvard Law School and Harvard Kennedy School, but to the kid at an elementary school somewhere who reads these stories and understands their history, what has happened, and what’s at stake.

HLT: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Brooks: I would just note the immensity and radicality of Mrs. House’s work. Here is a woman who never took a course on legislative advocacy, who never took a course in civil litigation, but who files a lawsuit seeking reparations for elderly enslaved people, funded by the tax imposed on cotton harvested by formerly enslaved people. She, notwithstanding the fact that W. E. B. DuBois and Booker T. Washington did not assist her in these efforts, supports federal legislation for reparations a century before H.R. 40 [legislation filed in the House of Representatives that would create a commission to study and develop reparation proposals for African Americans].

And, no less of an infamous figure than Senator Edmund ‘Segregation’ Pettus supported the legislation because he understood that if Black people received funding, white people might benefit. In other words, this woman is a massively underappreciated, but monumentally consequential, figure in American history.

Sullivan: The last thing I’ll say is that the presidential pardon is a power that is vested in the president and is virtually unfettered. President Biden can do this tomorrow. There’s a moral imperative that he do it and do it quickly. And we would urge people — average ordinary, everyday citizens — to make their voices heard, and to prevail on him to exercise his pardon power.