Wine connoisseurs have a term for the way the soil, wind, weather, and even culture of a place impact the taste and experience of a glass of Chardonnay or Pinot Noir: terroir.

It was while filming a documentary about the fight over the legalization of medical cannabis that Rebecca Richman Cohen ’07, a lecturer at Harvard Law School and Emmy-nominated filmmaker, first learned of the term. And it sowed the seeds of her next documentary.

“I became curious if craft cannabis was laying a claim to the idea of terroir in the way that wine long has,” she says.

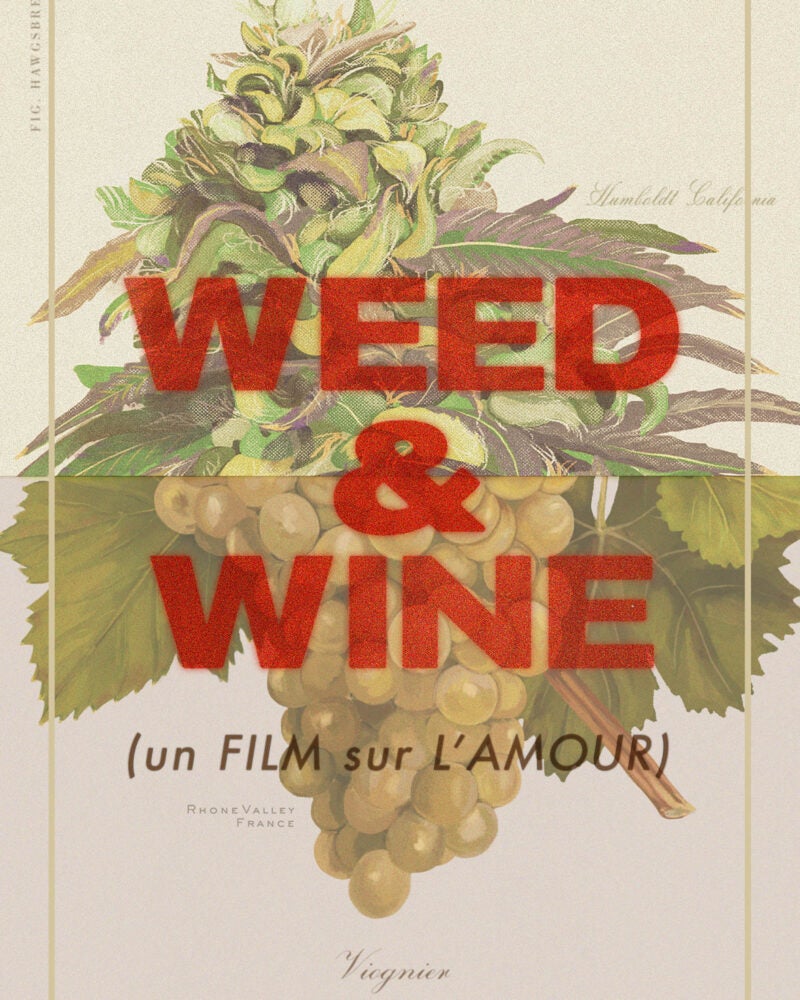

Her latest film, “Weed & Wine,” asks just that, delving into the rich and layered stories of two agricultural families — one American, one French — dealing with age-old questions about passion, legacy, and relationships, along with modern problems like climate change and shifting cultural values.

The film is a slight departure for Richman Cohen, whose previous works have often probed tensions within law and society, such as the trial of a former rebel leader in Sierra Leone, Florida’s sex offender laws, and the aftermath of the #MeToo movement’s call for tougher sentencing for perpetrators of sexual assault.

But her new feature has roots in two prior films, including “The Fight Over Medical Marijuana,” a New York Times Op-Doc, which followed a federal raid of medical cannabis growers in Montana in 2012. That short film — and decades of work by drug policy reform activists — led the Times editorial board to unanimously call for the end of the federal prohibition on marijuana.

It also resulted in a full-length film, “Code of the West,” scenes of which were shown in the sentencing phase of the participants’ criminal trials, Richman Cohen says.

“That was a hard and heavy film,” she adds. “And so, we wanted to tell a different kind of cannabis story. A more playful one!”

“Weed & Wine” centers on Kevin and Cona Jodrey, a father-son duo in far northern California who cultivate craft cannabis, along with Hélène Thibon and her son Aurélien, who are part of a centuries-old tradition of winemaking on their vineyard in France’s Rhone Valley.

While there are obvious differences between the families — Kev is a self-described “outlaw” who began growing marijuana decades before it gained legal status in California, while the French winemakers are part of a nationally cherished industry — they share similar struggles, from wanting to safeguard their product and processes, to ensuring that their land and livelihood continue into the next generation.

When searching for the subjects of her film, Richman Cohen connected with the Jodrey family quickly, thanks to contacts she had made while producing her previous documentaries. “Kev is an incredibly dynamic, seasoned craft cannabis cultivator. He was a perfect fit for this project,” she says.

But finding a winemaker willing to participate proved much harder. “The wine world is skeptical of the comparison to cannabis, which is still illegal in France, and there’s a huge amount of stigma around it,” she says.

Finally, she reached the Thibons. “They immediately understood the analogy that we were making, that there are similarities and differences between all agricultural products, including grapes and cannabis,” the filmmaker says. They were really interested in partnering with us to tell this story.”

Initially, Richman Cohen had planned to focus mainly on that connection, she says. “But once we started rolling, all of the beauty and the tensions inherent in family dynamics began to unfold, and the film became something very different than we originally imagined.”

In some important ways, both families have been shaped by the crop they grow, especially its legal and social status. “Kev had worked on the illicit cannabis market for decades,” she says. “He is very upfront about that. He is an outlaw, and he raised Cona in that world.”

Ironically, Richman Cohen says, California’s legalization of marijuana in 2016 “decimated” the craft cannabis industry, shrinking the number of growers in Humboldt County from 15-30,000 farms to fewer than 300 licensed farms in operation today. The Jodreys’ business was among the casualties.

And while Hélène and Aurélien are part of their country’s winemaking heritage, they are rebels in another sense, she says.

“Although the Thibons never broke the law, I think they are pirates in other ways. They are part of the natural wine movement,” Richman Cohen says. “In the film, Hélène says something like, ‘Freedom isn’t flittering about from one thing another. It’s about choosing your rules and then staying within them.’ And for them, it means they are doing things their own way, making wine that is true to the terroir, even if it bucks norms and conventions.”

This dedication comes at a cost, she adds: Their wines are not included in France’s Appellations of Origin, a system of organizing and labeling the country’s wines that can impact their retail value, and to some, lend more credibility.

Besides telling the deeply personal stories of farmers and their connections to the land and to one another, Richman Cohen says she hopes her film connects to audiences as well. And the story does not end there. She recently launched a fundraiser to produce a sequel to “Weed & Wine” and hopes that the series could end up something like the British TV series “Seven Up!,” which began in 1964 and continues to follow the lives of a group of people to this day.

“We want audiences to stay with us on this journey for the long haul. The story doesn’t end here,” she says.

Filmmaking and Harvard Law

Richman Cohen’s approach to filmmaking is, in at least a few ways, informed by her time as a Harvard Law student. Not long after arriving on campus in 2004, she soon realized something important: Despite caring deeply about human rights and the power of the law to make change, she did not actually want to practice law.

Instead, she wanted to make movies. But rather than telling her to drop out, she credits her Harvard Law mentors with supporting and encouraging her foray into filmmaking, even as she completed her legal studies.

“I started filming my first feature-length documentary when I was still a third-year student, and it was based off my internship the previous summer,” she says, adding that she was privy to an abundance of resources as a student.

Since then, her films have tackled many intense and often morally complicated issues, frequently including a legal dimension. “It’s not very interesting to make a film strictly about a regulatory structure,” she jokes. “It’s much more interesting to make a film about the human experience, about the people whose lives are impacted by those structures.”

“It’s not very interesting to make a film strictly about a regulatory structure … It’s much more interesting to make a film about the human experience, about the people whose lives are impacted by those structures.”

Today, in addition to filmmaking, Richman Cohen teaches two courses at Harvard Law on the power of film and its ability to influence law and policy. She is also dedicated to her mentorship of students through the Harvard Law School Film Society.

“I’m excited to support students, especially those who may have similar ambivalence about practicing law but want to take their legal education and put it to use in other creative ways,” she says.

As Richman Cohen teaches her students, the visual arts can be an invaluable part of changing hearts and minds — but only when filmmakers partner with people and organizations working on problems on the ground. “If we build an outreach campaign to support the ongoing efforts of activists, nonprofits, movement leaders, we have a real shot at meaningful change.”

And although “Weed & Wine” is not really an advocacy film, Richman Cohen says, she nonetheless hopes that her new work inspires people to look closer at their preferences.

“Many people are willing to pay more for organic vegetables,” she notes. “For folks who consume weed, would you also consider paying more for organic, sun-grown cannabis? Until you learn the stories of the farmers behind it, maybe not. But we hope to raise that awareness, and we hope to do that in partnership with organizations that are doing great work in this space.”

After all, for centuries, the wine world has used the concept of terroir — stories about the land, farmers, and even the spirit of a place, to connect to its consumer base, Richman Cohen says. “Why not cannabis?”

Want to stay up to date with Harvard Law Today? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.