When asked what he wanted to be remembered for, longtime Harvard Law Professor and former Watergate prosecutor Philip B. Heymann ’60 replied: “Speaking truth to power.”

For Heymann, who died Nov. 30 at his home in Los Angeles from complications of a stroke, that principle would define a life of scholarship, teaching, and public service that would take him back and forth from Cambridge, Mass., to Washington, D.C. many times over the course of a six-decade career in the law.

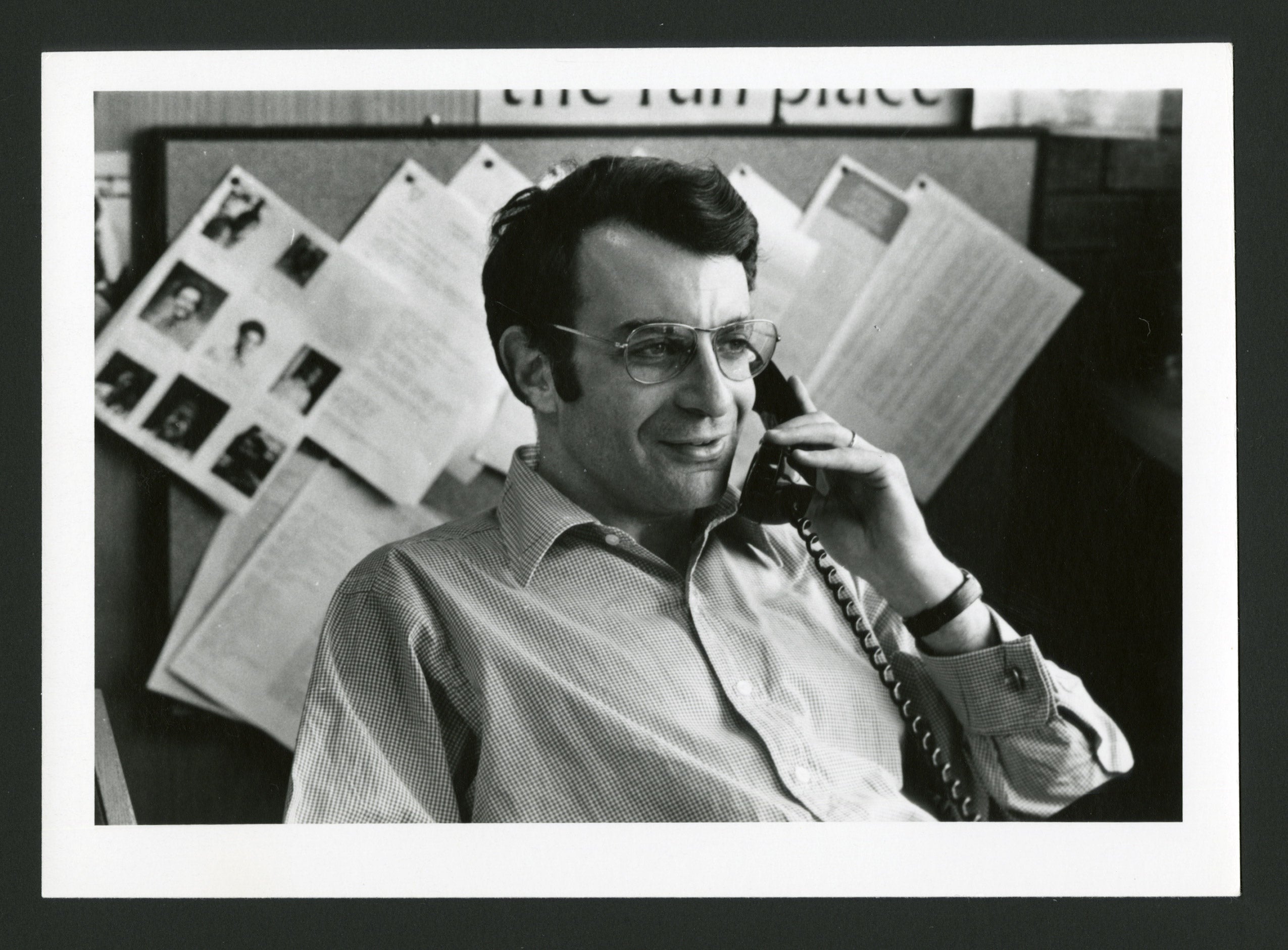

A highly principled public official and beloved colleague, Heymann had a distinguished career in academia, and serving in four presidential administrations, including in the solicitor general’s office under President John F. Kennedy, in several U.S. State Department jobs for Lyndon Johnson, as a Watergate prosecutor, as assistant attorney general during the Carter administration, and as deputy attorney general under Bill Clinton.

In a New York Times obituary, his daughter, Dr. Jody Heymann, said: “He believed in government service. And even though he held positions of consequence, he saw himself as a civil servant. He believed that we all contribute to our government.”

News of his passing inspired an outpouring of praise and gratitude from colleagues and admirers across the nation, including the current and past deans of his alma mater and intellectual home.

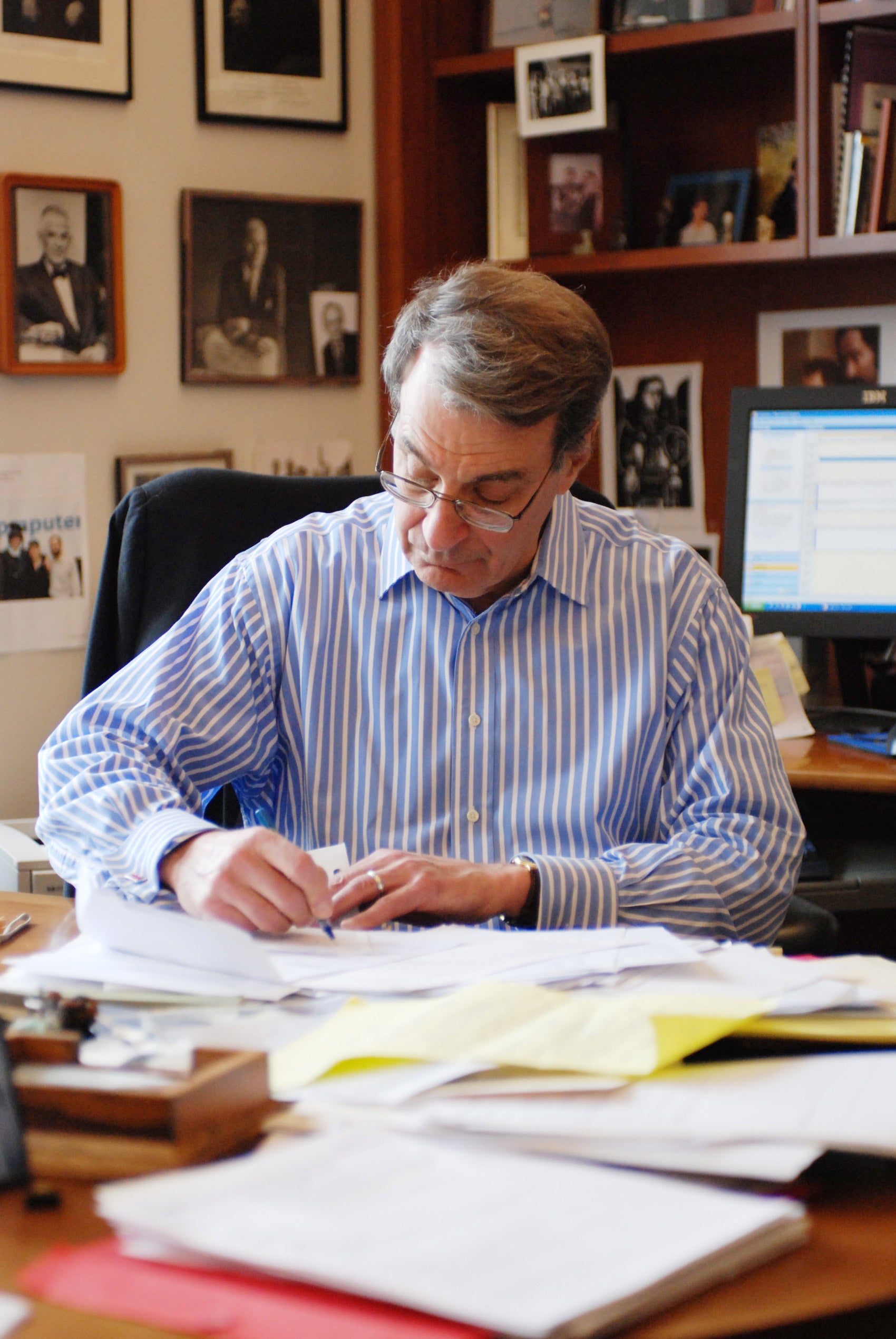

John F. Manning ’85, the Morgan and Helen Chu Dean and Professor of Law at Harvard Law, said Heymann brought energy, honesty, integrity, and common sense to all he did. “Phil led a highly consequential life of teaching, writing, research, and service. His research and teaching, like his public service, focused on solving problems, using the law as a way to make our society and our polity work better.”

“I am so grateful to have known and worked with Phil,” said Martha Minow, the 300th Anniversary University Professor. “His intellectual zest, devotion to public service, fantastic sense of humor, and deep wells of generosity exemplify the best of the law school and the profession. And there could be no better friend.”

After graduating from HLS in 1960 and clerking for U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan II, Heymann began his career in the solicitor general’s office, serving under Archibald Cox ’37, whom he described as his mentor and close friend. When Cox in 1973 accepted the appointment as special prosecutor in the Watergate scandals with the goal of restoring “confidence, honor and integrity in government,” among his first steps was naming his former student, Heymann, as chief assistant of the special prosecution team. According to Heymann, Cox was revered by young prosecutors as “absolutely righteous,” someone who was “absolutely determined to do the right thing.”

From 1965 to 1969, he held various positions in the State Department, including as acting administrator of the Bureau of Security and Consular Affairs, deputy assistant secretary of state for the Bureau of International Organizations, and executive assistant to the Undersecretary of State. Among other things, he was responsible for efforts to assist U.S. prisoners-of-war in Vietnam.

As assistant attorney general during the Carter administration, he oversaw the Department of Justice’s Criminal Division, where he supervised the investigation of the Jonestown Massacre and helped direct Abscam, a bribery sting operation which led to the convictions of a U.S. senator and six congressmen.

“Phil was widely admired, inside and outside the government, for his tough-mindedness, good judgment, and adherence to principle. And he was frequently consulted by administrations in which he was not serving — Democratic and Republican alike — on thorny issues that he had an uncanny ability to sort out,” said Jack Goldsmith, the Learned Hand Professor of Law and former assistant attorney general in the Office of Legal Counsel. “He believed in government’s potential goodness, but worried a lot about its foibles and abuses.”

Heymann’s government service influenced his scholarship and teaching. Over the course of his half century of service at Harvard Law School, he was a mentor to and inspiration for scores of students who went on to success in government and the academy.

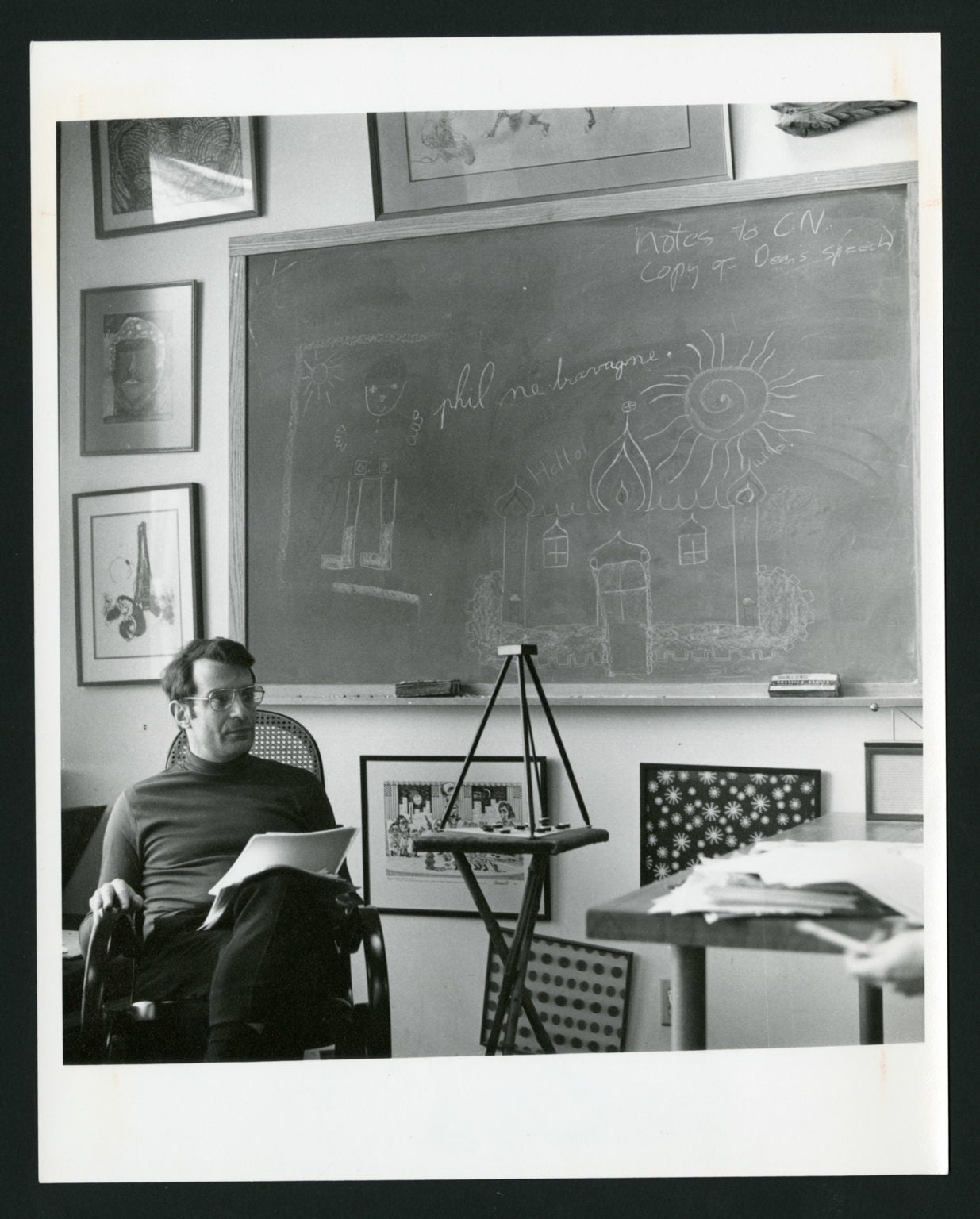

“As a 1L student who took Phil’s criminal law course in 1969, I remember well his long black sideburns and his 1960s vibe,” said former HLS Dean Robert Clark ’72 in a 2016 tribute on the occasion of Heymann’s retirement. “Throughout his long career, Phil has shown an unfailing commitment to the task of understanding how best to keep government and its officials accountable to fundamental social values, while nevertheless giving them power and showing them ways to achieve legitimate goals.”

Heymann — who studied philosophy at Yale and as a Fulbright Scholar at the Sorbonne in Paris, and served in the Air Force from 1955 to 1957, reviewing security clearances in the Office of Special Investigations before attending law school — began teaching criminal law and procedure at Harvard as a lecturer on law in 1969. He was named a professor of law in 1971, was appointed associate dean in 1985, and, in 1989, he was named the James Barr Ames Professor of Law. He also taught at Harvard Kennedy School, where he directed the program for senior managers in government.

At HLS, he directed the Harvard Law School’s Center for Criminal Justice, where he managed a number of projects designed to improve the criminal justice systems of countries seeking to create or preserve democratic institutions, including Guatemala, Colombia, South Africa, and Russia. He also served as senior counsel to Common Cause, a citizen’s lobbying organization promoting open government.

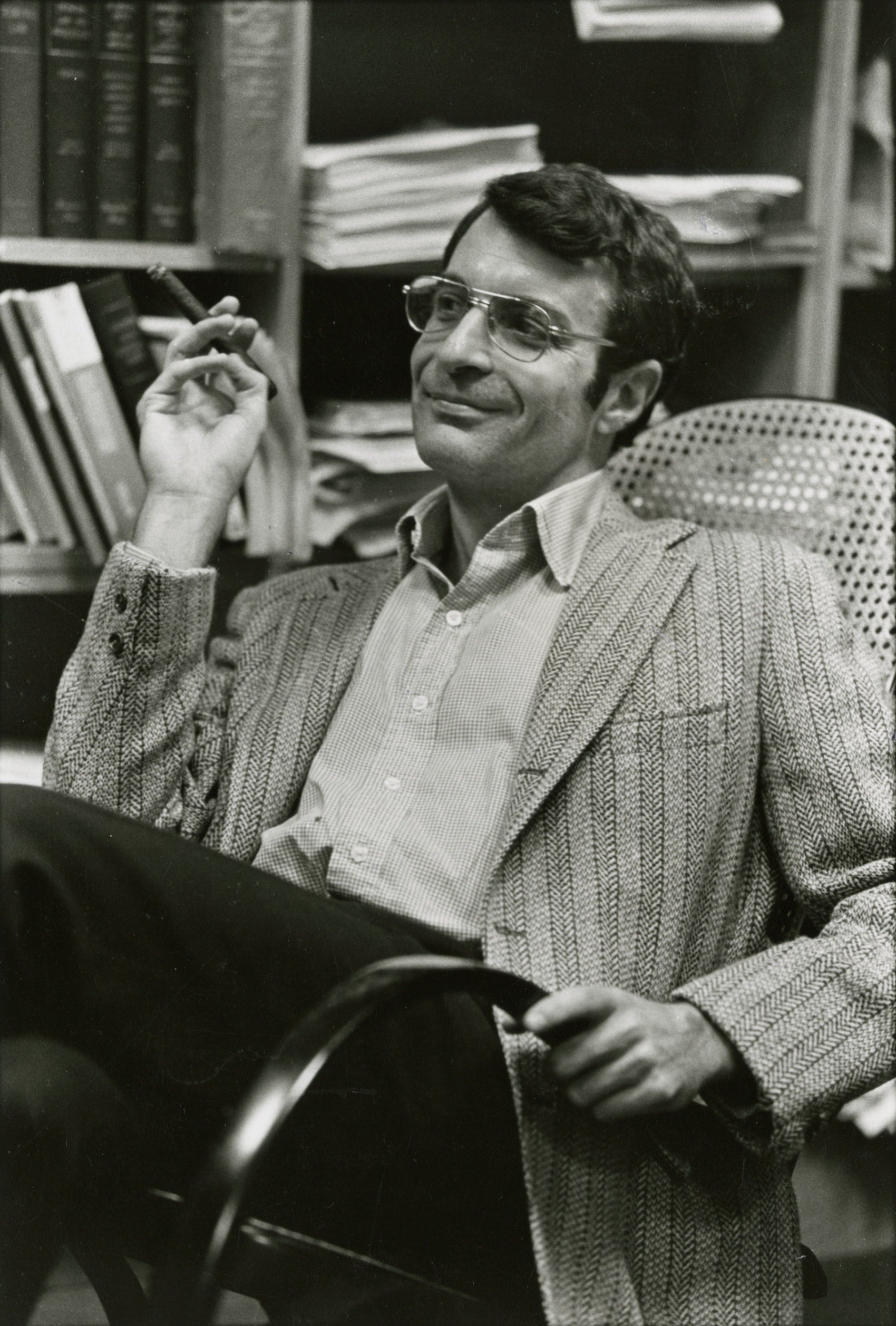

Drawing on his own experience, he wrote “The Politics of Public Management” in 1987, which explored how political appointees cope with the powerful political forces that surround them.

In 1993, Heymann returned to public service when President Clinton nominated him as deputy attorney general under Attorney General Janet Reno ’63. His first official task was investigating the Justice Department’s handling of the 1993 standoff between federal agents and members of the Branch Davidian sect near Waco, Texas, where more than 80 people died.

After seven months on the job, Heymann abruptly resigned citing differences in management style.

In a press conference the day after his resignation, Heymann, who had operated as one of the administration’s most senior criminal justice policy makers, publicly criticized the Clinton Administration’s multibillion-dollar crime bill, arguing that proposed provisions to impose mandatory minimum sentences for low-level drug offenders and lock up repeat offenders for life without parole (“three strikes and you’re out”), would be costly and have a negligible effect on crime.

After returning to Harvard Law School in 1994, he wrote and edited seven books and numerous articles on crime and terrorism. Among his most highly acclaimed contributions are his works concentrating on good policy responses to terrorism.

“He focused on solving real-world problems, the harder the better, including targeted killing, interrogation, organized crime, drug addiction, and prosecutorial abuse,” said Goldsmith. “Phil’s solutions were characteristically legally acute, data-driven, imaginative, pragmatic, constructive, and always attentive to rights and liberties.”

He wrote “Terrorism and America: A Commonsense Strategy for a Democratic Society” (1998), and “Terrorism, Freedom, and Security” (2004), which argue that we must preserve our civil liberties and democratic values while fighting terrorism.

With Juliette Kayyem ’95, Harvard Kennedy School professor and former assistant secretary in the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, he co-directed a project to review some of the most difficult legal issues posed by America’s security, convening experts across the political spectrum to devise clear rules to guide government action in a “war on terror.”

They co-wrote “Protecting Liberty in an Age of Terror” (2005), which provides a legal framework for policymakers faced with decisions on coercive interrogation, detention, electronic surveillance, targeted killing, racial profiling, and related issues.

“Phil wasn’t just an exceptional scholar and public servant. He was unapologetically optimistic, believed in the power of ideas, energetic in all things, and loved a good laugh,” said Kayyem. “For so many students and colleagues, he was the person who never doubted them. It is a rare quality, to be so generous and supportive, and we are all lucky to have been in his orbit.”

Describing Heymann as her mentor and colleague, Gabriella Blum LL.M. ’01 S.J.D. ’03, the Rita E. Hauser Professor of Human Rights and Humanitarian Law and vice dean for the Graduate Program and International Legal Studies, said, “He was indiscriminately kind to everyone he interacted with and was much quicker to find virtues than flaws in his interlocutors.”

Blum, who co-wrote “Laws, Outlaws, and Terrorists” (2010) with Heymann, said, “He studied political and criminal violence, and wrote seminal works on terrorism long before these topics featured on the front pages. He understood politics, institutions, and the best and worst of human nature.”

In 2019, with his son Stephen P. Heymann ’82, a former federal prosecutor, he co-wrote “Challenging Organized Crime in the Western Hemisphere,” which explores how organized crime groups develop their capacities in response to heightened powers of law enforcement.

Heymann’s greatest influence was on his students and young attorneys, among whom he was renowned as a mentor and role model.

“I met him before I was even a student,” said Will McConnell ’22, who served as Heymann’s last research assistant. “As an anonymous 24-year-old, I emailed to him a piece that I had written on separation of powers. He was remarkably gracious, read my paper, and, to my incredulity, invited me to write a book with him on the professionalism and dedication of public servants.”

McConnell worked nearly full time together with Heymann for a year-and-a-half, co-writing the still unpublished “War Stories.” The book, McConnell said, refutes the notion, promoted by some in the political sphere, that a “deep state” of Washington bureaucrats controls the government and thwarts the will of the people.

At the end of one of the chapters, Heymann wrote: “There is no “deep state” in the policy world of law enforcement; there is a deep, protective culture that affects in a consistent way the decisions of hundreds of thousands of officials involved in the policy area. It cannot be found in secret code books of meetings of armed conspirators. The culture exists in our Bill of Rights, in thousands of Supreme Court decisions, in tens of thousands of other court decisions, and in millions of pages of manuals and other training material. It is rooted in hundreds of years of fear of unbridled powers at home and buried deep in the reaches of the patriotism behind our wars against tyrants.”

He is survived by his wife Ann Ross Heymann, his two children, four grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren.