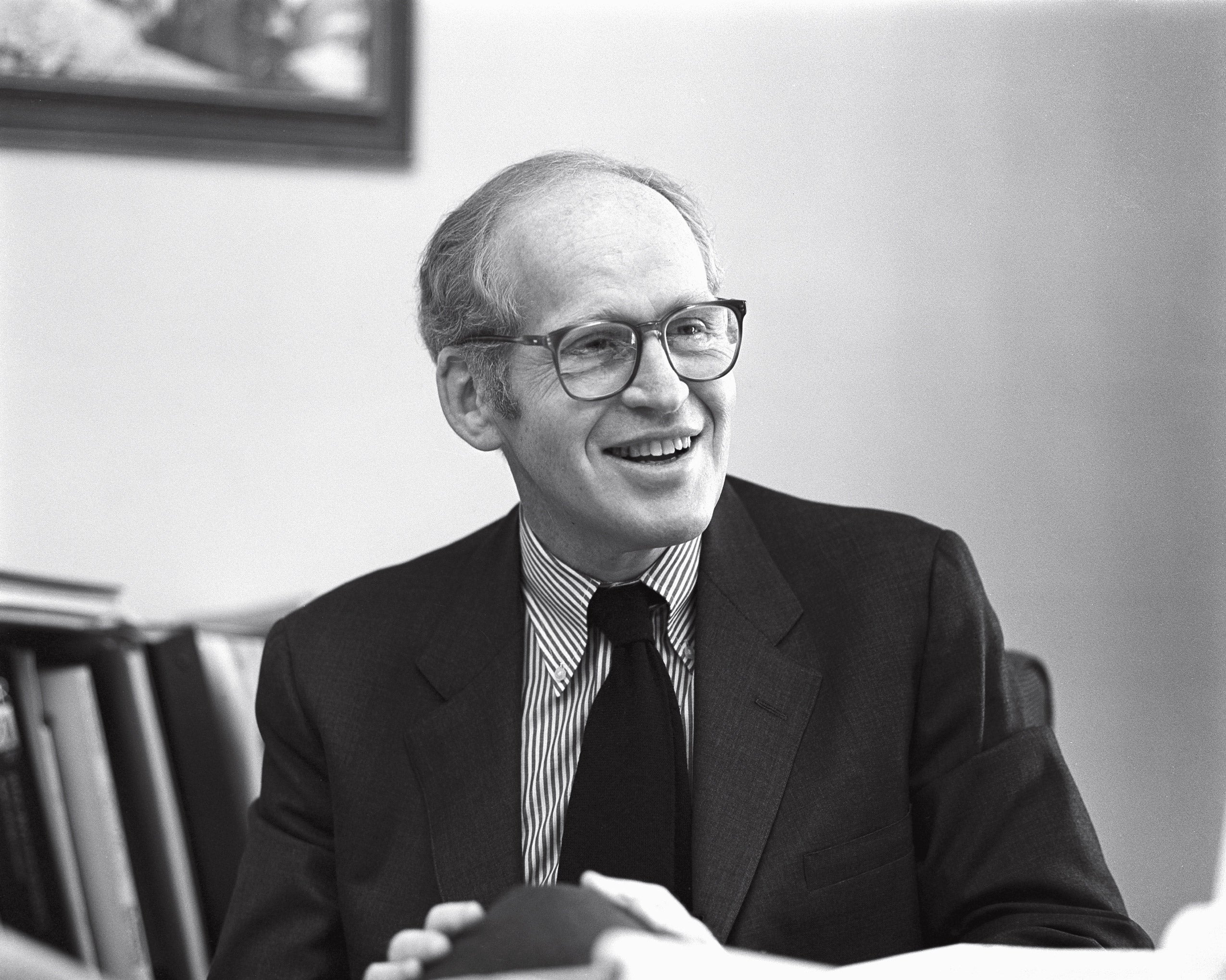

Alan A. Stone, the Touroff-Glueck Professor of Law and Psychiatry Emeritus in the faculties of law and medicine at Harvard University, died Jan. 23. He was 92.

Trained in psychiatry and psychoanalysis, Stone was a dominant figure in the ethics of psychiatry and forensic psychiatry. Deeply committed to intellectual engagement, he was well read across multiple disciplines — psychiatry, law, literature, and film — and was the voice for ethics in the legal and medical systems during his more than five-decade teaching career at Harvard.

“Alan’s wisdom, honesty, insight, fearlessness, compassion, and intellectual and moral integrity helped him reshape both law and medicine on vital questions arising at the intersection of both fields. Though not a lawyer, he had deep insights about law — and helped the lawyers around him gain richer understandings about our work and our profession,” said John F. Manning ’85, the Morgan and Helen Chu Dean and Professor of Law at Harvard Law School. “He was so widely read, so curious, so engaged with the world around him. He always had something insightful and interesting to say about films, about great books and plays, about science and medicine, and about human beings and humankind. … All of us who were his friends, his colleagues, and his students were fortunate indeed to know this extraordinary person.”

Stone’s influence on the law and on psychiatry has been profound. During his tenure with the American Psychiatric Association, where he served as president from 1979 to 1980, he challenged psychiatry’s use in public policy and successfully lobbied to have homosexuality removed as a psychiatric diagnosis from the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.” He was also involved with controversial questions about psychiatric ethics in South Africa, the Soviet Union, and China.

His writings encompass more than 100 books, chapters, and articles, many of which have been influential in the legal and medical professions, some directly influencing Supreme Court opinions. His landmark book “Law, Psychiatry, and Morality” explores how moral reasoning can elucidate problems of law, ethics, and the treatment of the mentally ill and has been widely cited.

Stone entered the field of law at a time of “challenge to the assumption that psychiatry and psychoanalysis were value-free sciences,” and spent his career examining the moral implications of psychiatry.

In his keynote address at the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law’s annual meeting in 1982, “The Ethics of Forensic Psychiatry: A View From the Ivory Tower,” he argued that psychiatry was burdened with hidden moral biases, and he was sharply critical of the prevailing ethics standards of forensic psychiatry. His critique was later described as having “reverberations on a national scale.”

In a controversial 1995 address to the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, he argued that while analysis has failed as a treatment for mental illness, it can still relieve “ordinary suffering.”

In 1993, he served as a member of the U.S. Justice Department’s behavior science panel tasked with evaluating government action at Waco, Texas, where a standoff between federal agents and members of the Branch Davidian sect, led by David Koresh, resulted in the deaths of more than 75 people. On the Waco Commission, he was critical of the government’s assault. In a minority report, submitted to then Deputy Attorney General Philip Heymann ’60, Stone criticized the government’s handling of the negotiations, concluding that the government failed to give adequate consideration to their own behavioral science and negotiation experts’ assessment of Koresh’s psychopathology before “embarking on a misguided and punishing law enforcement strategy that contributed to the tragic ending at Waco.” In later interviews, he said he feared that until mistakes made at Waco were acknowledged, they would continue to fuel extremism.

Stone, who grew up in East Boston, enrolled at Harvard College in 1946 as an economics major, with the intention of going to law school. A sophomore year course which explored the phenomenon of conversion sparked his interest in psychology. Stone, who was a starting lineman on the Harvard football team, wrote his senior thesis on “Violence and Aggression in Football,” and graduated in 1950 with a degree in psychology.

He went on to earn an M.D. from Yale Medical School in 1955, and trained in psychiatry at McLean Hospital in Massachusetts, where he served as director of residency training from 1961 to 1968, while serving as a lecturer at Harvard Medical School. He completed his psychoanalytic training at the Boston Psychoanalytic Institute.

Stone’s career in law began by chance when, in 1965, HLS Professor Alan Dershowitz invited him to co-teach “Psychoanalytic Theory and Legal Assumptions” at Harvard Law. They went on to co-teach “Psychiatry and the Law.”

In 1968, Stone took a yearlong sabbatical to study law and shifted his primary focus from medicine to law. He was named a professor of law and psychiatry in the faculty of law and the faculty of medicine at Harvard in 1972, and, in 1982, he was named the Touroff-Glueck Professor of Law and Psychiatry.

At Harvard Law, he designed a law and medicine curriculum, teaching “Psychiatry and the Law,” the “Psychoanalytic Theory,” “Clinical Dimensions of Mental Health Law” and “Law and Medicine,” among other courses. His interests included the right to treatment, economics of the medical profession, ethics of forensics, right to die, and political misuse of psychiatry.

In 1975, he wrote a monograph, “Mental Health and Law: A System in Transition,” aimed at acquainting policymakers, judges, and program administrators with recent developments in law and mental health. The book formulated positions on standards for civil commitment, the determination of competency to stand trial and the right to refuse treatment, among other issues, and earned Stone the American Psychiatric Association’s Manfred S. Guttmacher Award.

During his five-decade tenure at Harvard, his courses expanded to cover topics including law and literature, film, and violence. One of his most popular courses, “Justice and Morality in the Plays of Shakespeare,” included a staged trial of Hamlet, sometimes with U.S. Supreme Court Justice Anthony M. Kennedy ’61 presiding.

He also contributed film reviews to the Boston Review, a collection of which were published in 2007 as a book, “Movies and the Moral Adventure of Life.” Another volume, “The Abnormal Personality Through Literature,” illustrated sociopsychological manifestations and effects of mental illness through excerpts from world literature.

“For half a century, Alan Stone illuminated desires, fears, passions, and emotions of human beings that are so central to law — while he also involved students, colleagues, and readers in his deep and searching explorations of literature, films, and life’s meaning,” said Martha Minow, the 300th Anniversary University Professor and former dean of Harvard Law School. “I will always remember his quips, insights, and advice as well as his intellectual curiosity and his kindness.”

Upon Stone’s retirement in 2017, a professorship in his name was formally instituted at Harvard Law. Endowed in 2007 by his sons, David (’84) and Douglas, it was temporarily called the Alfred Smart Professorship, in recognition of Stone’s father-in-law. When asked at the time to name his major accomplishment at the school, Stone said, “to bring humanism to the law school.”

Professor Jon Hanson, the inaugural holder of the professorship named for Stone, said: “I’ll never forget how supportive Alan was when I, as an assistant professor, began exploring social psychology and other mind sciences. Alan had a lifetime fascination with the human experience and behavior, which manifested as bountiful erudition spanning from psychiatry, philosophy, and history to law, literature, and cinema. His encouragement gave me the confidence I needed to prioritize pursuing questions I cared about over fidelity to a method. More important, Alan provided everyone lucky enough to know him a beautiful model of how to live: warm, generous, eager to engage and laugh, and brimming with love for friends and family. To put it in movie-review terms, Alan’s life was a tour de force. The greatest privilege of holding a chair in Alan’s name are the frequent reminders it provides me of him, of how he lived, and of who I aspire to be.”

In addition to his two sons, Douglas and David, Stone is survived by his partner, Laura Maslow-Armand ’92; six grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren. His wife, Sue (Smart) Stone, died in 1996. His daughter, Karen Stone Zieve, died in 1988.

Related Reading

“Alan A. Stone, 92, Dies; Challenged Psychiatry’s Use in Public Policy” (New York Times)