Fifty years ago, the Special Olympics was founded as a summer camp for people with intellectual disabilities. Over the past five decades, it has grown to a global movement, working in more than 170 countries on a daily basis to empower people with intellectual disabilities through sports, education and health programs, and educate the broader public about the ways in which genuine inclusion benefits all.

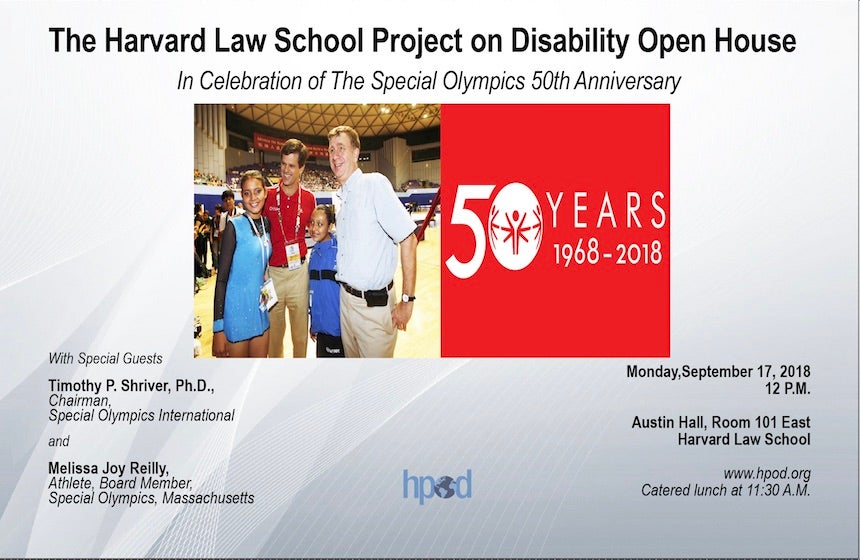

On Sept. 17, the Harvard Law School Project on Disability (HPOD) will bestow its fifth annual HPOD Award for the Betterment of Humanity to Special Olympics on the occasion its historic anniversary.

The event, which will take place in Harvard Law School’s Austin Hall, will include Special Olympics International Board Chairman Dr. Timothy Shriver and Melissa Joy Reilly, an athlete who competed in two Special Olympics World Winter Games, and now works in the office of Massachusetts State Senator Jamie Eldridge and the Learning Program of Boston.

Harvard Law School’s Project on Disability, founded in 2004 by Professor William Alford ’77 and Visiting Professor Michael Ashley Stein ’88, has worked to advance the understanding of disability law, policy, and education worldwide. Alford, Chair of HPOD, has been a member of the board of Special Olympics International for all but one of the past 14 years, and now serves as its Lead Director and Chair of the Executive Committee. An internationally recognized disability expert, Stein, HPOD’s Executive Director, was instrumental in the drafting of the landmark United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. They will present the award on behalf of HPOD.

The HPOD Award recognizes individuals and organizations dedicated to making the world a better place for all its inhabitants. Previous recipients include Justice Albie Sachs of the Constitutional Court of South Africa, Justice Rosalie Abella of the Supreme Court of Canada, Ambassador Luis Gallegos of Ecuador, Professor Gary Siperstein of the University of Massachusetts and Professor Han Dayuan, Former Dean of Renmin University of China Law School.

Alford, the law school’s Vice Dean for the Graduate Program and International Legal Studies, has focused his academic work on China, its legal history and its effort to develop its legal system, and increasingly, also disability law. In 2007, Alford and Stein organized China’s first conference on disability law and rights, in conjunction with Renmin University of China and the China Disabled Persons’ Federation. Alford’s involvement with Special Olympics for more than two decades has allowed him to bring together his many interests and work collaboratively with Chinese colleagues to build civil society.

In a Q&A with Harvard Law Today, Alford discusses HPOD’s connection with the Special Olympics and its impact over the past 50 years.

What is the connection of HPOD to the Special Olympics?

Initially, the connection was through me, but happily it has grown and multiplied so many people are involved. I have worked as a volunteer in various capacities for Special Olympics for decades now. I started with that because I worked with Sargent Shriver who was chair of the Special Olympics. His wife, Eunice Kennedy Shriver, was its founder. So what does HPOD do with Special Olympics? As we do with many organizations, we bring our comparative and international law learning, particularly in the area of disability, to bear on our public interest work. Michael Stein and Dr. Fengming Cui and I have gone several times to give talks for Special Olympics about the U.N. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities or disability law issues in the U.S., China, or other countries. We all take part in a range of Special Olympics activities. Professor Stein has led wonderful training programs in Cambridge, some on the Harvard campus. He teaches self-advocacy skills to persons with intellectual disabilities, some of whom are Special Olympics athletes. And on the more playful side, in Hemingway gym a few years ago we hosted Dikembe Mutombo, Michelle Kwan, and the rest of the Special Olympics International Board playing floor hockey, with local Special Olympic athletes and Harvard men’s varsity ice hockey team.

How has Special Olympic evolved over the past 50 years and what is its impact.

It really has changed a great deal over the years. I would say Special Olympics these days rightly stresses the enormous contributions that persons with intellectual disabilities give to the rest of society. As inspiring an organization as it has been from its inception, that’s a different emphasis. Initially, the focus was more on what the rest of us could do for persons with an intellectual disability and I think we’ve been trying more of late to stress the things that we all can learn from persons with intellectual disabilities. So what do I mean by that? Incredible determination, courage, inclusion, generosity. And I really mean that. The life lessons that I’ve had the good fortune to witness are just incredible. The way human nature is, people tend to sometimes write off or be patronizing about individuals with an intellectual disability. One should not underestimate what people are capable of doing if they have the opportunity and encouragement. We’ve seen amazing things that people have done. I think there’s a lot to learn, particularly given how fractured our world is these days, from the inclusiveness and spirit of Special Olympic athletes.

How has your work with Special Olympics informed your academic work in China

My first trip to China for Special Olympics was in 1979 when I went with Mr. Shriver, but that didn’t lead to anything immediately. When conditions in China warranted, in the 1990s, things did begin to blossom. I’ve been going to China for my own academic work forever, and in the last 20 years I’ve tried to do more with respect to disability issues there. Special Olympics has been one vehicle for that, although we also have our Harvard program which has wonderful, strong collaborations with Chinese colleagues in the area of disability. For me personally, it’s been especially gratifying because when I go to China, whether it’s 30 years ago or yesterday, people always want to know what I’m working on, what I think is interesting, what I think is important, in part because I’m a professor at Harvard Law School, and I’m pleased to use that opening to draw their attention to disability. We’ve been very fortunate, we’ve identified a group of Chinese academics and lawyers who genuinely are interested in this area and I’ve learned a lot from them. Many of them have come up with ideas for all kinds of things we could do together. We have a terrific and mutually beneficial collaboration between Harvard and Renmin University of China Law School. It’s been a great way to connect to China at a time when there are many fractious political issues between the U.S. and China, this is one that really does bring people together. And I believe that the public interest work we do has created a lot of goodwill for Harvard.

This work has certainly informed my writing and teaching. To give you a concrete example, years ago when we first started to do disability work in China, many former students and friends were kind and supportive, but almost to a person they said that, historically, China had not been particularly benevolent in its treatment of persons with disabilities. For a variety of reasons I didn’t want to accept that at face value. I thought, if you accept that things have been tough and therefore they’re going to be tough, it’s almost self-defeating. And it also seemed, as a student of Chinese history, that with 5,000 years of rich, complicated history, it perhaps wasn’t as uniformly bleak as people were telling me. So I decided to do research on the history of disability in China. And although there is certainly a foundation for some of the negative portrayals, just as there is in much of the West historically, I’ve also identified five different threads of a more benevolent approach toward disability issues in imperial China–in philosophy, government policy, law, social practice (clans and groups outside of government) and self-help of persons with disabilities. I’ve done a couple of papers about that which have gotten a very positive reception in China. People are really curious, because they just assume their past is entirely bleak and one, that’s not true, and two, if you’re trying to build something in China today, it can’t be 100 percent an import. You really have to have roots in Chinese soil to be sustainable.

This also informs my teaching in some ways, because, again, at a time when there’s a lot tension in the U.S.-China relationship on many fronts, this is one area in which there is a lot of shared interest. Our Chinese colleagues at Renmin University are great. It’s really an equal partnership. They’re pushing us as much as we’re pushing them. They’re coming up with new ideas. I think they’re really determined to make a mark in making society better. So it’s been gratifying. It’s also been good for Harvard Law School. As I mentioned, to be involved in a pretty substantial pro bono project in China bears out an important dimension of what this place is about.

Because of the extent of things that we’re doing in China, it also gives me a kind of practical hands-on experience about Chinese institutions that I think I would otherwise only be able to get by doing consulting for a business. I’m able to see what it means to implement something new in China, how the law in a very concrete way works in particular areas, and what it means to foster legal development. For me this is a very comfortable and exciting way to glean a lot of hands-on experience that I can bring back into the classroom. It’s not just talking about China at a remove of 6,729 miles, but it’s really dealing with concrete everyday challenges and opportunities.

So, please join us at our Open House Monday at noon to experience our work for yourself.