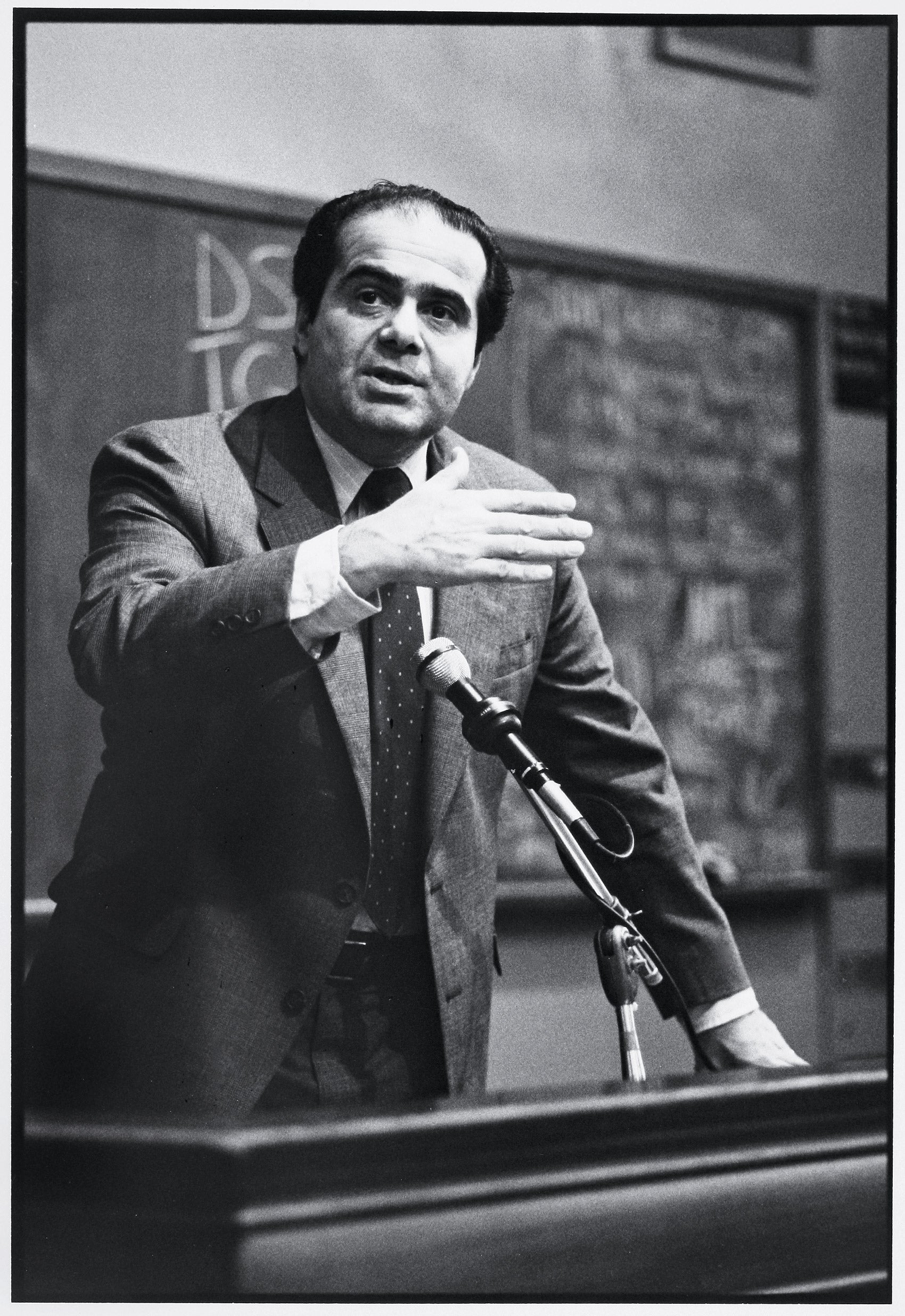

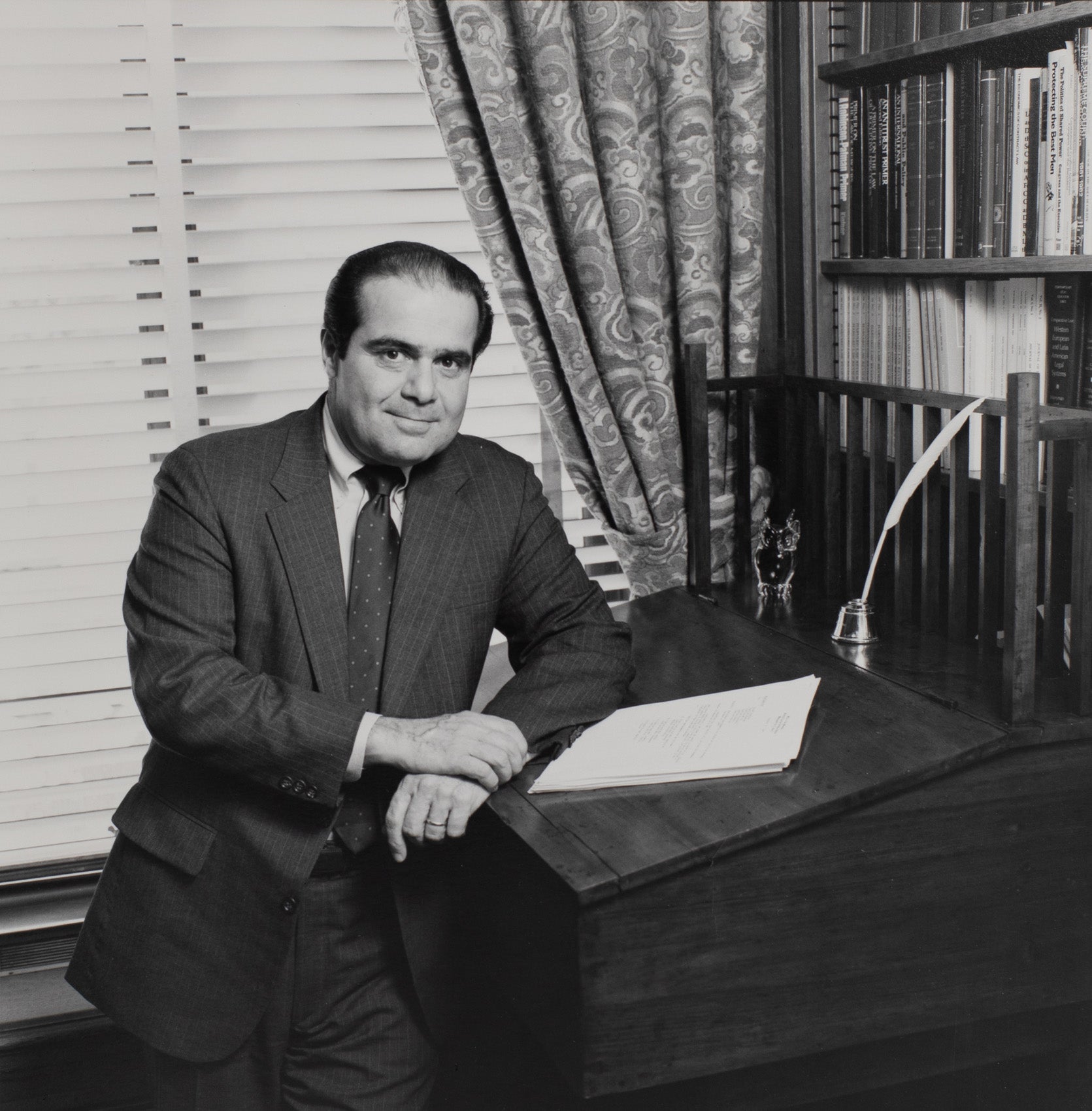

With the passing of Justice Antonin Scalia ’60 of the U.S. Supreme Court on Feb. 13 has come an outpouring of remembrances and testaments to his transformative presence during his 30 years on the Court. On Feb. 24, Dean Martha Minow and a panel of Harvard Law School professors, each of whom had a personal or professional connection to the justice, gathered to remember his life and work.

Professor John F. Manning ’85

Law Clerk, Justice Antonin Scalia, 1988-1989

“I clerked for Justice Scalia almost 30 years ago, when he was a young man and a fairly new justice. … What struck me immediately about my new boss was that for him, it was all about the ideas, about mixing it up, about arguing so that you’d come out closer to the truth. Sometimes, he’d have to remind us, ‘Hey, it’s my name that’s going on the opinion.’ And sometimes, that would be followed by, ‘And I’m not a nut.’ But that just underscores how free he made us feel to express ourselves and to disagree with him. … Justice Scalia was also a natural teacher. He would always tell us that part of what we were entitled to as law clerks was to understand the Court. And so after every conference, he would call all five of us into his office and ask us each to predict case by case and justice by justice how the case had been decided by the Court. It was unspeakably fun, and he was always playful about it. And he’d rewrite our drafts from top to bottom—well, at least he would rewrite mine from top to bottom. And he would always tell us why, and it would help us learn.”

Professor Lawrence Lessig

Law Clerk, Justice Antonin Scalia, 1990-1991

“It’s puzzling to many of my friends why I am an admirer of Justice Scalia. Justice Scalia’s politics, his personal preference, his judgment in many cases, are all things I would say I disagree with. But I can’t escape the fact that he profoundly affected how I thought, how I think about the law. … [T]he experience that was most meaningful to me was to sit as a law clerk and watch him struggle with what he knew his principles said he should do, and what he wanted as a conservative to do. … In every single case where we saw that conflict, Scalia did what his principles said he should do. … When people of great power demonstrate their willingness to restrict their power in the name of something—whether you agree with it or not—it is moving.”

Professor Richard Lazarus ’79

Supreme Court Advocate

“[Justice Scalia] changed the way lawyers argue cases. He changed our framework. And so, too, he changed the way the justices, and all judges, analyze cases. Arguments became better, more rigorous, more precise, and less sloppy, and it was true for both written briefs and oral arguments. It will be strange to stand up before that bench and not have Scalia there. I cannot say I’ll miss his vote. … Justice Scalia was environmental law’s greatest skeptic. In cases I have done, he has been my most persistent nemesis. While I won’t miss his vote, I will miss his voice. And I’m grateful for his enormous public service and contributions to a nation he clearly adored.”

Professor Adrian Vermeule ’93

Law Clerk, Justice Antonin Scalia, 1994-1995

“I want to make a suggestion about the justice’s ruling virtue. I think it was courage. So many people remarked on his brilliance, his joie de vivre, his loyalty. I think all those are true, but I think that courage underlies them all in some essential way. … His brilliance [wasn’t] just a function of IQ, but it stemmed from a kind of courage to follow a chain of reasoning wherever it might lead and ignore the socially induced constraints and self-censorship that so many times caused us to stop short in our reasoning. His joie de vivre is famous. He was a man bubbling with good humor. I think that’s, in part, a product of courage, too. Fear’s great enemy is joy, and this is a man who was joyful because he was often unafraid. And his loyalty [was] courage not to fall away, not to deny a person or deny one of his commitments even when the whole world was clamoring for him to deny them.”

Professor Cass Sunstein ’78

Colleague of Antonin Scalia, Law Faculty, University of Chicago

“I want to say two things that are kind of questions in the spirit of Justice Scalia’s own love of argument. I think that he was not at his very best when his convictions were most intensely felt. Some of his technical opinions are kind of transcendently good, where his convictions were kind of red in color—not communist but deeply felt. The large abstractions, I think, being less enduring than they would otherwise have been. That’s one question. The other question has to do with the existence of originalist blind spots. There are areas … —standing, affirmative action and takings are three—where the historical record is not clearly supportive of his ultimate judgments. And I think it’s fair in the spirit of welcoming contestation to wonder whether the positions he defended in those three areas were compelled by or were consistent with the original understanding. Still, Justice Scalia was not just a very significant justice; he was also a superb one. You’re blessed to be working in law in the time when Justice Scalia was on the scene.”

Professor Emeritus Frank Michelman ’60

Classmate of Antonin Scalia, HLS Class of 1960

“I think my friend Nino was an exceptionally gifted man in many ways, of which I stand sometimes almost in awe. … I admire [Justice Scalia] for sticking his neck out, putting out on the table a method for judging constitutional cases, a judicial philosophy, as we sometimes grandiosely call it. … So, what do we think, and what will history say about that judicial philosophy’s suitability to the time and the country and the conditions in which it was brought to bear? What do we think about its founding premise? Do we really do best to treat our Constitution as a lock-in for more or less specific political ideas and conceptions accepted by majorities and on their minds at the time of the formation? Would we do better to treat it as an open-ended pointer toward a better future and continued progress toward liberty and justice for all? Is the answer sometimes one and sometimes the other?”

Dean Martha Minow

“ … ‘Just call me Nino.’ That’s the first exchange that I had with Justice Scalia. I was a dean; I met a lot of famous people. That’s not usually how the conversation begins. His warmth and his willingness to just be genuine were what overwhelmed me. And in each of the interactions that I had with him, that was the overriding experience. His interest in having a genuine conversation, connecting about family, about religion, about law, about ideas, thorough, complete, generous and engaging. At the same time, he knew I didn’t agree with almost anything that he actually concluded, whether it was his methods of interpretation or where he came out in many cases. It didn’t matter to him. In fact, I think it made it a plus.”

Professor Charles Fried

Former U.S. Solicitor General

“I have known, I knew, Antonin Scalia since 1985. … And whether it was meeting him at a Federalist Society jamboree for really young lawyers over pizza and beer, or at the poker table, or arguing to him on the Supreme Court, or watching him as others argued to him, one came away with a sense of energy. And now he’s gone. Well, he’s not, because of his writing, which we will encounter in generations to come. And so I thought I would just give you a little bit of that voice. … He is in that great trilogy, of Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Robert Jackson and Scalia. But there’s a difference. Let me give you one fairly characteristic to me, Holmes in Buck v. Bell: ‘Three generations of imbeciles are enough.’ It is not an argument. It is not the conclusion of an argument. It is just what he said. … But it’s memorable. In McAuliffe v. Mayor of New Bedford, [regarding] a policeman who’d been fired for engaging in political activity: ‘The petitioner may have a constitutional right to talk politics, but he has no constitutional right to be a policeman.’ That isn’t the conclusion of the argument; that’s the whole argument. Well, compare that to Jackson … in the steel seizure case: ‘I am quite unimpressed with the argument that we should affirm possession of [emergency powers] without statute.’ And his line ‘Such power either has no beginning or it has no end.’ That is not the whole argument. It is the summation of an intricate, careful argument, which any law student knows, which goes on for pages. But the maxim sums it up. And that is the case with Scalia. There are memorable maxims, but they either introduce or sum up a careful, intricate and memorable original argument. In the independent counsel case Morrison v. Olson, the maxim comes by way of introduction. ‘That is what this suit is about. Power. The allocation of power among Congress, the President, and the courts in such fashion as to preserve the equilibrium the Constitution sought to establish. … Frequently an issue of this sort will come before the Court clad, so to speak, in sheep’s clothing. … But this wolf comes as a wolf.’ And there follows an original and remarkable piece of analysis. It’s not just the maxim.”