For centuries, the Takla Lake First Nation people have lived in a remote area of northern British Columbia on land that is inextricably linked to their culture, spiritual life and livelihoods. In recent times, their land—rich in mineral and timber resources—has been the target of Canada’s mining industry, with current mining law allowing anyone to go online and buy a claim. About one third of their 27,000 square kilometers of territory is currently staked out in mineral claims.

Mining and mineral exploration, which have brought jobs and important revenue to the province, have also disturbed the wildlife and the environment on which the community depends. Some people have stopped hunting and fishing for fear of contamination.

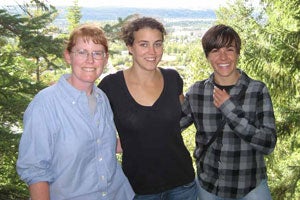

Last year, as part of Harvard’s International Human Rights Clinic, Susannah Knox ’10 and Lauren Pappone ’11, traveled to British Columbia with Lecturer on Law and Clinical Instructor Bonnie Docherty ’01 to investigate how mining affects the Takla Lake First Nation people.

Working with Docherty for the entire year, Knox and Pappone helped research aboriginal law, analyze existing mining laws and draft what would become a 200-page report. In June, the clinic released the report, “Bearing the Burden: The Effects of Mining on First Nations in British Columbia,” which found that the province’s laws favor mining interests over the aboriginal rights of Takla and other First Nations. The report calls for the government to give First Nations more say in how their traditional lands are used.

“Everything about their traditional culture is also about the land that they have lived on and their ancestors lived on,” said Knox. “You can’t just take that away and say, well, ‘go somewhere else and practice your culture.’ It doesn’t work that way.”

The clinic’s fact-finding mission in September 2009 took the students to Prince George and the Takla’s territory. They flew by floatplane to some of the more remote areas where the people of Takla live. They interviewed members of Takla and witnessed firsthand the effects of mining activity, visiting several sites, including an abandoned mercury mine from the 1940s.

“We talked to families whose traditional land was on or near that site and they told us stories of how they found vials of mercury in the old cabins and used to play with it,” said Knox.

The team later conducted interviews with provincial government officials and industry representatives.

The report received significant media attention and sparked public discussion. The clinic is now determining how it can best continue to address the issue in future projects.

This fall, as Pappone begins her 3L year at HLS, Knox will start work as an associate attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center in Chapel Hill. Both described the experience as a highlight of their law school education.

“It just meant a lot to me to finish this report, and make it really good and effective and informative,” said Knox. “It’s really nice to feel like you’re doing something that makes a difference.”