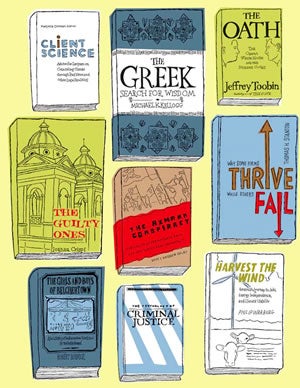

“Client Science: Advice for Lawyers on Counseling Clients through Bad News and Other Legal Realities,” by Marjorie Corman Aaron ’81 (Oxford). No one likes to deliver bad news—attorneys included. But oftentimes providing honest and difficult advice is a crucial part of the job, and Aaron offers her own advice on how best to do it. The former executive director of HLS’s Program on Negotiation and now professor at the University of Cincinnati College of Law shows how to bolster the lawyer-client relationship and ultimately enhance legal practice.

“The Guilty Ones,” by Joanna Crispi ’81 (NYQ). In her third novel, Crispi’s experience as a criminal defense attorney informs the tale of an HLS alumna who gives up that career to live abroad with her husband, a Parisian banker, only to be upended by his arrest in a Rome airport. According to the author, the premise of the book stems from the lessons she learned as a young attorney assisting Professor Alan Dershowitz on the Claus von Bulow appeal.

“The Girls and Boys of Belchertown: A Social History of the Belchertown State School for the Feeble-Minded,” by Robert Hornick ’70 (University of Massachusetts Press). Through the story of a state school in Massachusetts, Hornick exposes the history of society’s negligent treatment of people with intellectual disabilities. The Belchertown State School and other such institutions, he writes, served “as venues of quarantine rather than pedagogy” for those whom the state at one time called “the idiots of Massachusetts.” The author recounts the abuses of the residents that took place at the school and its eventual closure in the early 1990s.

“The Greek Search for Wisdom,” by Michael K. Kellogg ’82 (Prometheus). The author offers a cultural and historical introduction to ancient Greece and devotes chapters to the period’s most compelling authors and their writings. An appreciation of these masterworks, ranging from the epic poetry of Homer to the drama of Sophocles to the philosophy of Plato, enriches our lives and enlarges our sensibilities, Kellogg writes. His goal is “to take the measure of human wisdom and the highest reaches of the human spirit.”

“The Axmann Conspiracy: The Nazi Plan for a Fourth Reich and How the U.S. Army Defeated It,” by Scott Andrew Selby ’98 (Berkley). The Nazi threat did not die with Hitler, as Selby recounts in this previously untold history of the post-World War II attempt to re-establish Nazi dominance. The book tells the story of Artur Axmann, a member of Hitler’s inner circle who re-formed the Nazi party in Allied-occupied Germany, and the undercover work of U.S. Army Counter Intelligence Corps Officer Jack Hunter and other agents who discovered and thwarted the conspiracy.

“In Doubt: The Psychology of the Criminal Justice Process,” by Dan Simon S.J.D. ’94 (Harvard). The professor of law and psychology at the University of Southern California explores the investigative biases that can cause injustice even in seemingly open-and-shut cases. Grounded in a comprehensive review of psychological research, the book shows breakdowns that can occur through faulty evidence collection, coercive interrogations, mistaken eyewitness identifications and jury misunderstanding. Simon proposes reforms that, even in light of imperfect human cognition, he contends will improve the accuracy of verdicts.

“Why Some Firms Thrive While Others Fail: Governance and Management Lessons from the Crisis,” by Thomas H. Stanton ’70 (Oxford). In a twist on Tolstoy, the author contends that when it came to surviving the financial crisis, unsuccessful firms were all alike; every successful firm was successful in its own way. Stanton, who served on the staff of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, outlines how failed concerns like Countrywide neglected to manage risk and calls for leaders to “promote higher quality organizational design and management.”

“The Oath: The Obama White House and the Supreme Court,” by Jeffrey Toobin ’86 (Doubleday). On the cover of Toobin’s latest book, two of the most prominent HLS grads stand face to face: President Barack Obama ’91 and Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. ’79. When it comes to the Constitution, however, they rarely see eye to eye, as the author outlines in a book that illuminates a battle between two branches of government and two “honorable and intelligent” men. At its root, the conflict pits Roberts’ desire to use his position “as an apostle of change” against Obama’s determination “to hold on to an older version of the meaning of the Constitution,” writes Toobin.

“Harvest the Wind: America’s Journey to Jobs, Energy Independence, and Climate Stability,” by Philip Warburg ’85 (Beacon). In the face of America’s longtime reliance on fossil fuels, Warburg advocates harnessing an abundant alternative energy. The former president of the Conservation Law Foundation travels to places where wind power has thrived, such as Cloud County, Kan., and other rural areas of the Midwest, as well as farther afield to Denmark and China. While acknowledging the downsides of wind power, the author contends that it can help jump-start the economy and address the problem of climate change.

Judging the Meaning of Words

“Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts,” by Antonin Scalia ’60 and Bryan A. Garner (West). It may seem obvious to declare that words have meaning. But in the view of Supreme Court Justice Scalia and his co-author, known for his writing on language and the law, many judges need to learn that lesson. Describing themselves as textualists, they argue that “the established methods of judicial interpretation, involving scrupulous concern with the language of legal instruments and its meaning, are widely neglected.” And the consequences are dire, they write: unequal treatment of litigants, a distortion of governmental checks and balances, and a weakening of democratic processes. Their attempt to clear up confusion in the field of interpretation covers a wide range of language issues, including the use of the word “include” and how punctuation can indicate meaning, as well as an examination of historical cases. In one of them, the decision hinged on making a distinction between the meanings of the words “damage” and “damages,” exemplifying, as they write, the importance of “attention to text, and specifically to its original meaning, that we seek here to promote.”