When Heather Artinian ’18 walks on stage to receive her HLS degree later this month, it will be the culmination of 18 years working toward the goal of becoming a lawyer. Beginning as a 7-year-old, in fact, she was as sure as a child that young could be that law school would be in her future.

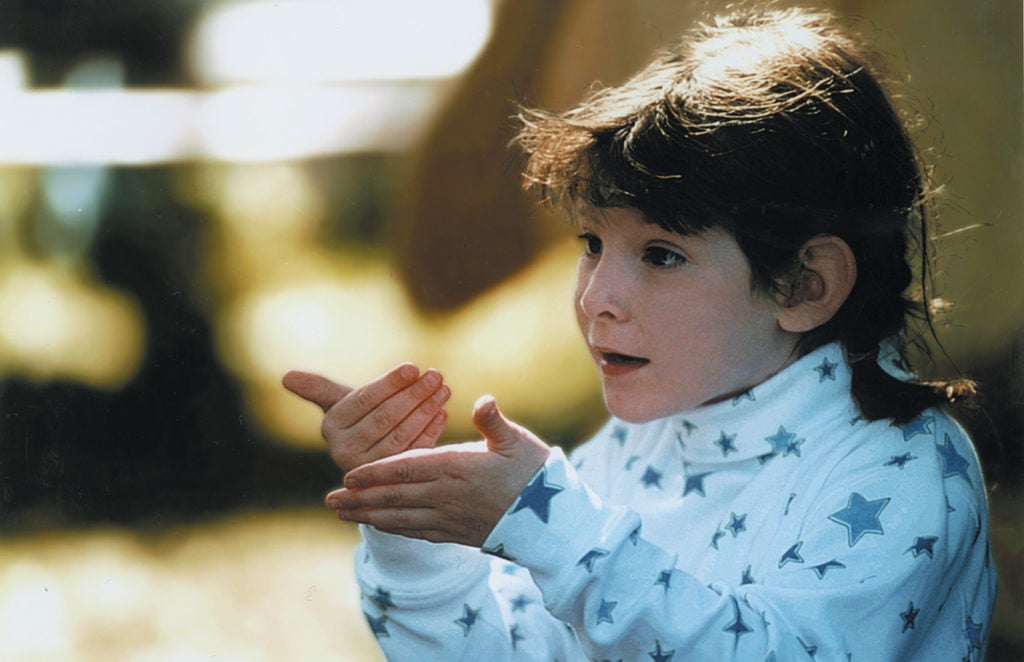

That was one of many ways she was not an average 7-year-old. By that age, she had been featured in an Academy Award-nominated documentary. A viewer can see she was an unusually precocious child as well, asking the type of pointed questions that would make a lawyer proud.

She also is deaf, and enough of an observer of the world even then to notice how her two deaf parents were treated by people who could hear. “It was almost as if they didn’t exist,” she recalls now. “Like they were invisible or people to be walked over. I remember watching them struggle to communicate and be taken seriously by their peers. That really upset me.”

Artinian told a teacher about the unfair treatment her parents faced, and asked what she could do about it. The answer: Become a lawyer.

She came to HLS aspiring to fight for justice and empower communities that are marginalized. As a student on campus, she simply wanted to be treated like everyone else, to have access to everything HLS has to offer its students, and to rise or fall on her own abilities.

The documentary, called “Sound and Fury,” chronicles a decision that has had a profound impact on her life. At the time, Artinian requested to receive a cochlear implant, an electronic device surgically placed under the skin that gives some deaf people the ability to hear sound. Her father in particular was against it as were other members of the deaf community, deeming it a rejection of deaf culture. By the end of the movie, Heather had agreed not to get the implant.

Heather Artinian ’18 as a child in a still from the documentary “Sound and Fury.” Made in 2000, the film chronicles her request to receive a cochlear implant. By the end of the movie, Heather had agreed not to get the implant because it was deemed by her father and other members of the deaf community as a rejection of deaf culture.

At that time, her family moved from a largely hearing community in New York to a community in Maryland with many deaf members with whom they communicated in sign language. Heather also went to a school for the deaf. The family later moved back to New York, where she said her father was denied a promotion at his workplace and told directly the reason was because he is deaf.

She asked her parents again about getting the implant. She said she is deaf and will always be deaf. But she also wanted every opportunity to be made available to her.

“I did not want anybody to have any reason to say no to me. It was never about being hearing,” said Artinian, comparing it to learning Spanish in a predominately Spanish-speaking country. “I just wanted to be able to communicate with the majority of people who live in this world who are hearing.”

At age 10 she did get the implant, and later was the only deaf person in a mainstream school. Having the implant has maximized her ability to integrate among hearing people while she still feels a sense of community with other people who are deaf, she says.

During her time at HLS, she has had two interpreters for the classroom and other campus activities, though she makes a point of going to social events without them (the implant is most effective, she says, when she is in a one-on-one conversation or in a small group). She typically tells hearing people who’ve never met her – and also often have never encountered another deaf person – that she won’t always understand their speech and they won’t always understand hers. After a while, people who get to know her, like they have at HLS, can forget she’s Heather a person who is deaf and think of her as just Heather.

There still can be obstacles in her path. Artinian recalls one professor who picked her name from a list of students to answer a question in class, but then, upon noticing that she was the student, said it was a mistake to ask her and posed the question to someone else. “That’s disappointing because it sends a message to students in class that I am somehow inferior or not able to answer the question or not as smart,” she says. Later she explained to the professor why skipping over her wasn’t appropriate, and the professor was apologetic. She will always speak up when she sees injustice, to make sure it doesn’t happen to the next person.

Artinian came to law school thinking her main interest could be constitutional law. But she took criminal law in her 1L year and loved it. She signed up for Harvard Defenders her first year and for the last two years has immersed herself in the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau, eventually becoming its intake director and typically devoting more than 40 hours a week there. As a student legal representative for HLAB, she has mainly worked on behalf of domestic violence survivors, in restraining order hearings and in family court. She was drawn to domestic violence cases because women in her family have experienced it and often people in marginalized communities are vulnerable to it.

“I wanted to do all I could to empower these survivors in the justice system in court because these communities don’t always have a voice, and I think that’s incredibly unfair,” she said.

After graduation, she will begin a job with Latham & Watkins in Washington, D.C., a firm that appealed to her because of its emphasis on pro bono work, she said. Someday she would like to effect change in the criminal justice system. No matter what her future holds, she has learned from a young age the power of being determined and persistent in order to achieve what is right.

“When people tell me no,” she said, “that just becomes more of a motivator for me.”

Spoken like someone who has wanted to be a lawyer for a very long time.