Since at least 1983, when a Harvard Law student wrote a third-year paper exploring a human rights argument for same-sex marriage, HLS has participated in anticipating, shaping, critiquing, analyzing and guiding the long path toward marriage equality.

In the 1980s, Harvard Law students wrote papers and student notes debating the pros and cons of a constitutional right to same-sex marriage in the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses. Those students graduated and became advocates who argued before legislatures and courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court, both for and against legal recognitions of same-sex marriage. Others eventually became judges whose decisions created a legal basis for marriage equality, and some became scholars whose contributions inspired a new generation of students, advocates, and judges to think critically and creatively about LGBT rights. Together, they helped shape the course of a social and legal movement that surprised many by its swift changes in both public perception and legal doctrine.

***

1983:

Evan Wolfson ’83 Pens Prescient Paper

In 1983, a decade after a fledgling movement for same-sex marriage came to a grinding halt in the courts, Harvard Law School third-year student Evan Wolfson asked a question that few in the mainstream legal world were seriously deliberating: Does the Constitution, and its myriad explicit and implied protections of expression, privacy and individualistic self-fulfillment, guarantee the right to same-sex marriage

Many of the arguments Wolfson made then, grounded in a historical framework of marriage as a human rights issue, would later shape legal arguments that would sweep the courts in the decades to come. Twenty years later, Wolfson built on his unpublished thesis in the book “Why Marriage Matters: America, Equality, and Gay People’s Right to Marry.” Published the year after Massachusetts became the first – and at that point only – state to legalize same-sex marriage, the book provided a legal analysis for why marriage should be a constitutional right for all.

***

1985:

Carol Steiker ’86 Explores Constitutional Status of Gay Persons

In “The Constitutional Status of Sexual Orientation: Homosexuality as a Suspect Classification,” a widely cited student note for the Harvard Law Review, Carol Steiker ’86, now a professor at Harvard Law, argued that legal classifications based on sexual orientation should be subject to heightened scrutiny beyond the “rational basis” test then used by courts. Steiker argued that the most commonly asserted constitutional foundations for gay rights – the right to privacy and the First Amendment guarantee of free speech and expression – had failed to overcome inequality, and that an equal protection approach would provide a richer framework to address discrimination against gay people. Equal Protection – as well as the Due Process Clause – would later serve as a chief tool for courts finding a constitutional right to same-sex marriage.

***

1986:

Laurence Tribe ’66 Argues to Strike Down Georgia Sodomy Laws

In 1986, the Supreme Court heard Bowers v. Hardwick, in which Laurence Tribe ’66 represented Michael Hardwick, a man who had been arrested by Georgia police under a state statute criminalizing sodomy. In a 5-4 decision, the Court upheld Georgia’s law, finding that prescriptions against sodomy “have ancient roots,” against which an argument for a constitutional right to engage in homosexual sex was, “at best, facetious.”

(In 2003 the Supreme Court overruled Bowers in Lawrence v. Texas, a case for which Tribe wrote the ACLU’s amicus curiae brief supporting Lawrence.)

***

1989:

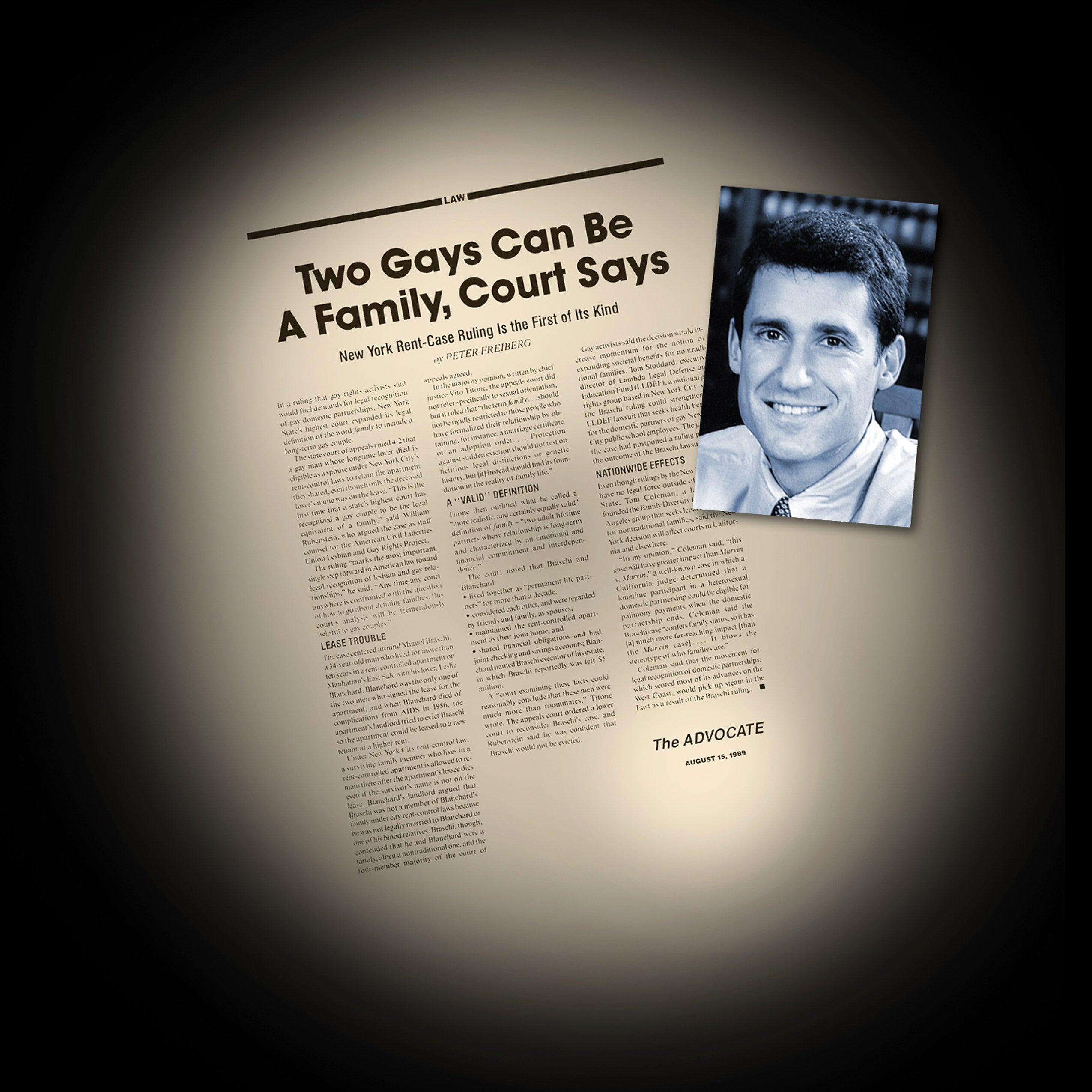

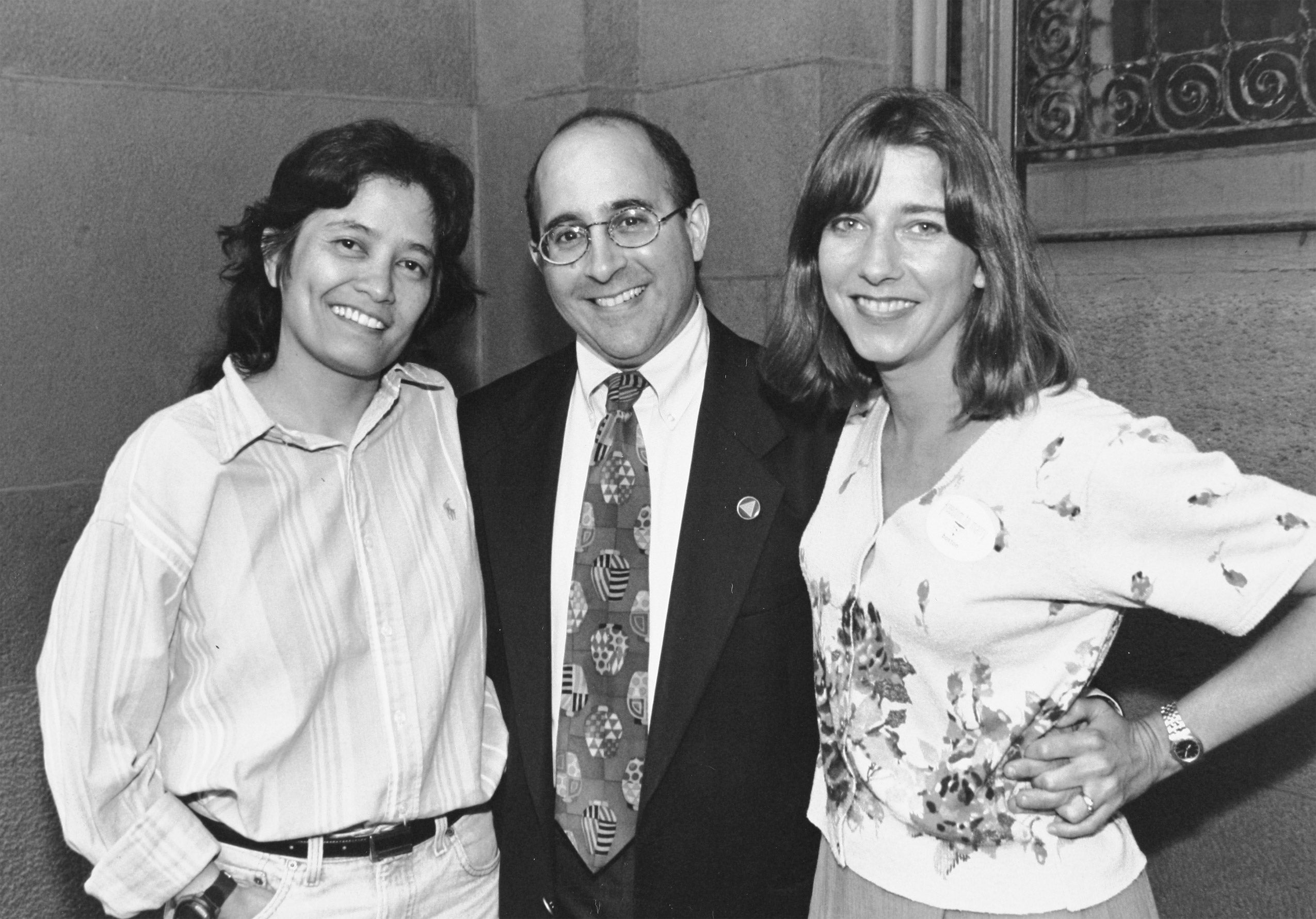

William Rubenstein ’86 Wins Legal Recognition of Gay Couples as Families

In 1989, William B. Rubenstein ’86, now a professor at Harvard Law School, convinced a New York court that the surviving partner and caretaker of a man who had died of AIDS counted as “family” under the state’s law, and could thus continue living in a rent-controlled apartment that had belonged to his partner. In Braschi v. Stahl Associates, New York became the first state supreme court to recognize a gay couple as a family, forging an important precedent at a time when there was almost no legal recognition of same-sex couples. After graduating from HLS, Rubenstein was a staff attorney and later director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s National LGBT and AIDS Projects, and in 1993 authored the first casebook on LGBT law, now in its fifth edition and known as “Cases and Materials on Sexual Orientation and the Law.”

***

1993:

Evan Wolfson ’83 Joins Landmark Hawaii Litigation for Legal Right to Marriage

In the mid-1990s, Evan Wolfson participated in landmark litigation, serving as co-counsel in Baehr v. Lewin, later Baehr v. Miike, a Hawaii case in which the state’s supreme court held that the state’s prohibition on same-sex marriage was discriminatory. The state’s highest court sent the case back to trial, where a lower court found in 1996 that the state had no rational reason to deny marriage licenses to same-sex couples. Backlash against the decision later led the state to amend its constitution to cement a ban on same-sex marriage, and inspired Congress to pass the Defense of Marriage Act in 1996. In 2003, Wolfson would go on to form the national advocacy group Freedom to Marry.

***

1996:

Jean Dubofsky ’67 Lands the First LGBT Rights Win at the Supreme Court

In 1996, after Colorado voters unexpectedly passed Amendment 2 to the state Constitution, which would have prevented local governments from recognizing homosexuals as a protected class, activists asked Jean Dubofsky ’67, an appellate attorney who had been the first woman to serve on the Colorado Supreme Court, to challenge the law. Although her goal was to get rid of Amendment 2 at the state level without landing in the U.S. Supreme Court, the Court eventually took the case, Romer v. Evans, and ultimately struck down the amendment as failing under the rational basis test of the Equal Protection Clause, marking the first win for LGBT rights in the Supreme Court.

It also sparked the beginning of a line of opinions by Justice Anthony Kennedy ’61 that, unlike the Court in Bowers, treated gay people as individuals with rights and dignity. “If you look back at Bowers and all the federal decisions after, their language was just horrific,” Dubofsky said. “They belittled people and made their claims seem frivolous and ridiculous. Romer treated people as if they had some dignity. I couldn’t believe it, when I read the opinion, how much of a sea change it was.”

***

2001:

Harvard Scholars Question Marriage as the Unifying Goal for LGBT Rights

As the legal fight for same-sex marriage began to trickle through the courts, Harvard Law Professor Janet Halley examined in 2001 what she viewed as the troubling rhetoric increasingly adopted by advocates for gay marriage. In an essay titled “Recognition, Rights, Regulation, Normalisation: Rhetorics of Justification in the Same-Sex Marriage Debate,” Halley expressed concerns that although limiting marriage to heterosexual couples indeed deprecated the relationships of gay couples who wished to marry, the fight for equality had too readily adopted language emphasizing the normative value of traditional coupling. Instead, Halley argued, the movement should question widespread assumptions about marriage and monogamy, leaving the door open for a broader range of non-traditional relationships.

In 2003, then-3L Douglas NeJaime published an article in the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review titled “Marriage, Cruising, and Life in Between” that explored a range of ideological positions through case studies of some of the leading gay-based organizations. NeJaime expressed concerns that the push for marriage would homogenize the LGBT movement and leave behind those who did not wish to advocate for traditional relationships or gay assimilation.

***

2003:

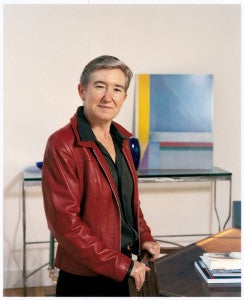

Chief Justice Margaret Marshall Pens Massachusetts Opinion Legalizing Same-Sex Marriage

On November 18, 2003, Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Chief Justice Margaret Marshall wrote the majority opinion for a divided court holding that the state’s ban on gay marriage violated the equal protection and due process rights of same-sex couples under the state constitution, making Massachusetts the first state to legalize same-sex marriage. Marshall, who in 2012 joined Harvard Law as a senior research fellow and lecturer, wrote a much-lauded and frequently quoted opinion that extolled marriage as a “deeply personal commitment to another human being and a highly public celebration of the ideals of mutuality, companionship, intimacy, fidelity, and family.”

***

2012:

Michael Klarman Reflects on Rapid Change

After dozens of states had legalized same-sex marriage – whether through legislation or the courts – Harvard Law Professor Michael Klarman authored “From the Closet to the Altar: Courts, Backlash, and the Struggle for Same-Sex Marriage.”

Klarman, who frequently writes about social backlashes that follow controversial court decisions, provided an overview of the growing legal acceptance of same-sex marriage and the role courts played in sparking or responding to social change.

September 2013:

Klarman, along with HLS Professors Tomiko Brown-Nagin, Charles Fried, and Visiting Professor Justin Driver offered their thoughts on a trio of critical U.S. Supreme Court rulings involving same-sex marriage, voting rights, and affirmative action.

***

2013:

Harvard Law Professors and Alumni Battle Before the Supreme Court

On June 26, 2013, the Supreme Court decided United States v. Windsor, which challenged Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act, and Hollingsworth v. Perry, a challenge to California’s Proposition 8. Months earlier, the Supreme Court had tapped Harvard Law Professor Vicki Jackson to argue that the Court lacked jurisdiction to hear Windsor, an argument that neither party to the case had presented, and which the Court ultimately rejected before ruling on the merits.

Paul Clement ’92 argued for the House of Representatives’ Bipartisan Legal Advisory Group, a contingent of mostly Republican representatives who argued to uphold the Constitutionality of DOMA after President Barack Obama ’91’s administration refused to continue doing so. In addition, Professors Elizabeth Bartholet ’65, Lawrence Lessig, and Laurence Tribe ’66, Professor Emeritus Frank Michelman ’60, and Lecturers Kevin Russell and Benjamin W. Heineman Jr., filed amicus briefs in the two major cases.

***

2015:

Mary Bonauto and Douglas Hallward-Driemeier ’94 Call for full Legal Recognition

Litigators across the country vied for the opportunity to argue for a constitutional right to same-sex marriage in some of the most anticipated cases in LGBT and civil rights history. In January 2015, the Supreme Court granted certiorari to Obergefell v. Hodges and its companion cases to answer the question whether the Constitution required states to perform same-sex marriages, or whether the Full Faith and Credit Clause required states to, at the very least, recognize same-sex marriages performed in other states. Mary Bonauto, who was also lead counsel for the couples seeking the right to marry in Goodridge and has taught an LGBT reading group at Harvard in recent years, was ultimately picked for the task of arguing the first question, while Douglas Hallward-Driemeier ’94, a partner at law firm Ropes & Gray, took on the Full Faith and Credit question. On April 28, 2015, the pair faced the Supreme Court justices, arguing, as Bonauto put it, that the true question was not whether the government should decide that gay people should be able to marry, but that it was for ” the individual to decide who to marry.”

November 2014:

In a conversation with Dean Martha Minow at HLS, Mary Bonauto reflects on a quarter century of seeking equal treatment under law.

***

2015:

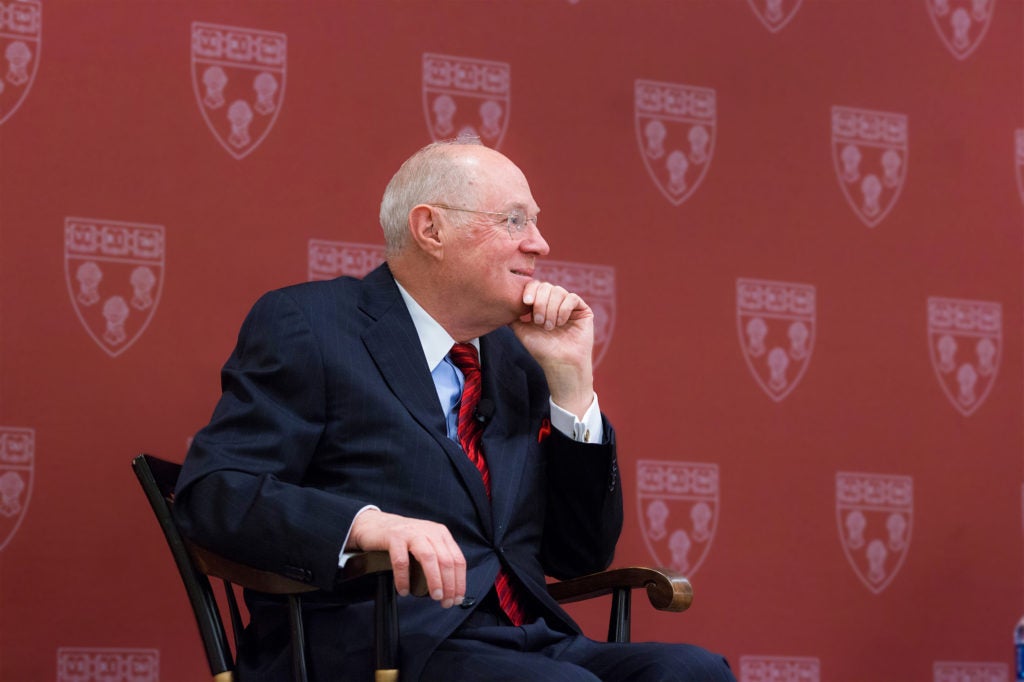

Justice Anthony M. Kennedy ’61 Writes Majority Opinion Affirming Marriage Equality

On June 26, 2015, the Supreme Court ruled in a 5-4 decision that the Constitution guarantees a nationwide right to same-sex marriage. Justice Anthony M. Kennedy ’61 delivered the opinion of the Court in the landmark decision. He was joined by Justices Stephen Breyer ’64, Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’56-’58, Elena Kagan ’86, and Sonia Sotomayor.