Maybe everyone will be surprised and Tuesday night’s presidential election will go off with no drama, no disputes and a clear winner in place by midnight. But given the strong possibility that won’t happen, a group of Harvard Law School students have launched a website that explores every other possible scenario.

The website, Electoral College FAQs, grew out of Professor Lawrence Lessig’s course “Presidential Elections: War Gaming 2020.” The course explores the history of the Electoral Count Act, a 19th-century statute which governs the Electoral College in ambiguous terms—and which opens up numerous, possibly disastrous, possibilities for the coming election. Students were expected to outline the open issues and possible complications, and to create a tool for public use.

The course, Lessig said, was inspired by an article that his co-instructor Matthew Seligman wrote. “He was writing about the consequences of a world where you can’t count on people acting in good faith. So, if people in Congress start not acting in good faith, what happens? Mapping that out led me to the course. The students were all eager to produce something they could put out there, and there were a lot of talents—one was expert at putting graphs together, another could coordinate the website, and they all did a ton of work to pull the information together. If the election is extremely close and we begin to see the games being played in states and Congress, the resources will help people understand how to follow and unpack it.”

Launched seven days before the election, Electoral College FAQs functions as a “make your own adventure” site, says Jack Jacobson ’22, one of the students who worked on it. Some sections are written for a general audience, while others go into enough depth to be useful to litigators who may work on election issues. “It gets increasingly specific as it goes on. For example, the first question on the FAQs is ‘Who elects the President?’ and the last is ‘What does “the legislature thereof” in Article II mean?’ So, it goes from the most easily digestible to the most dense and specific.” Other pages give interactive electoral maps, updated election data, links to relevant litigation and an archive of Lessig’s political podcast, Another Way.

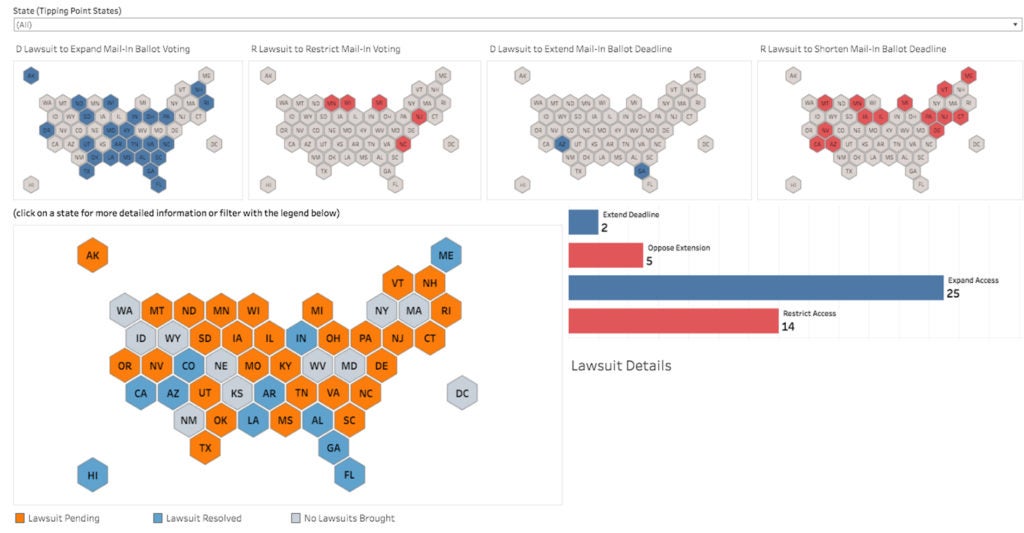

A portion of the site provides analysis of one potential scenario—the “Red Mirage”/“Blue Shift,” a phenomenon that could occur Tuesday in states where election-day votes, which may skew Republican, are counted before mail-in votes. Dinis Cheian, the course teaching assistant, lays out the possibility: “You might see in Pennsylvania, for example, that President Trump will have an edge that will be seen to diminish as the mail-in votes are counted. And so, he predicts, there could be “calls to stop counting the votes, court challenges, and so on.” The site provides graphics charting how this effect could play out in certain states as the night goes on.

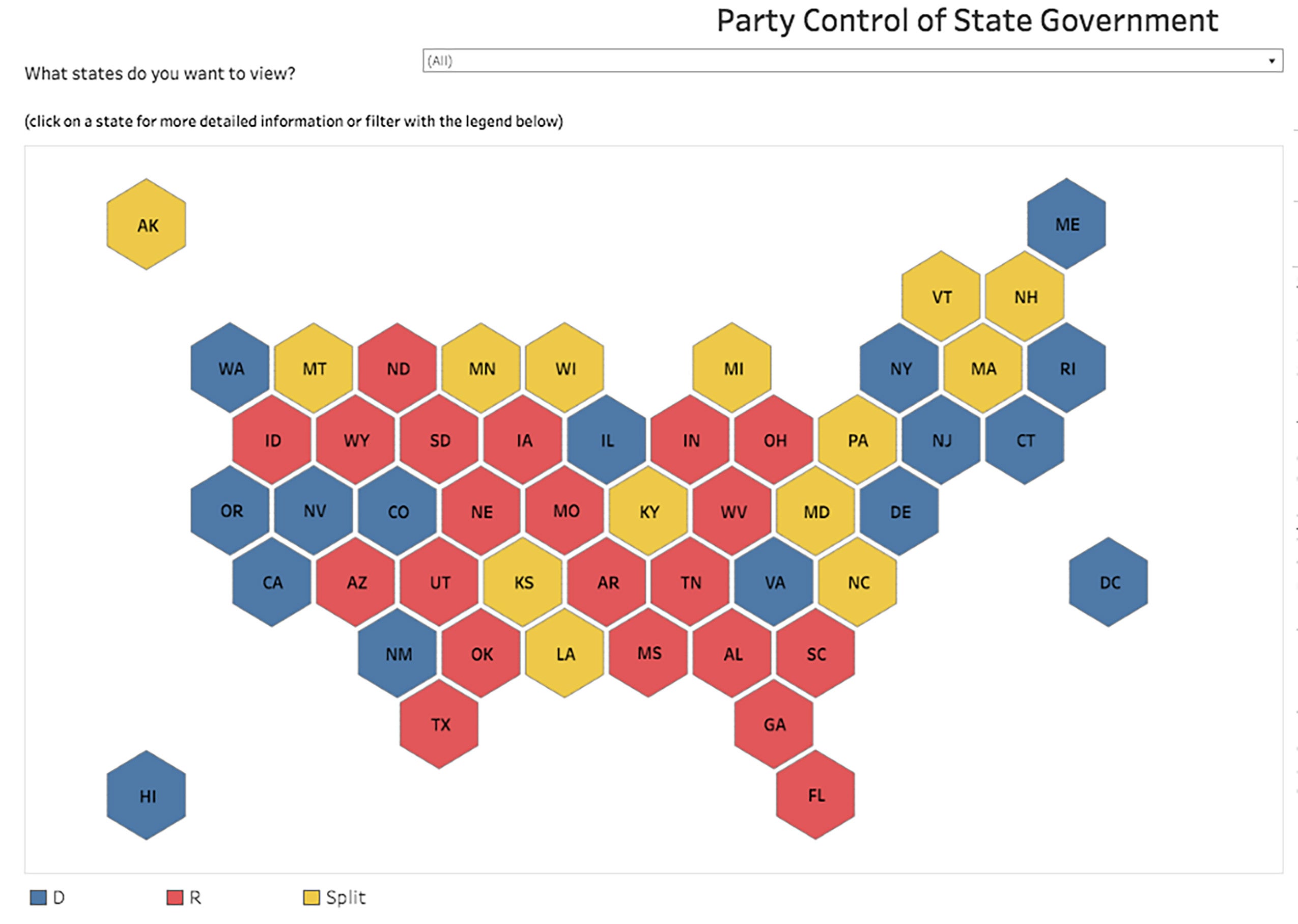

Other scenarios include the possibility of a state sending two different “slates” of electors to Congress to be counted—something that last happened in 1960, when Hawaii had an extremely close vote between John F. Kennedy and Richard M. Nixon—or a state declaring after Nov. 3 that electoral fraud had occurred. Says Cheian, “To assess that, you need to know the composition of the governors and the legislatures in different states. So, we have maps that summarize those details.”

“In doing this project, we’ve discovered the laws underlining our very system of democracy,” says student Steven Jiang ’21. “The general public may see it as: they cast a ballot, they watch it on TV, and that’s how the election works. But underlining that is an often-fragile system of laws that have many different weaknesses in terms of potential exploitation by people who might not want to see the results of their election certified. As we go through the course, we have been more expansive in terms of the scenarios that we have been envisioning and trying to preempt.”

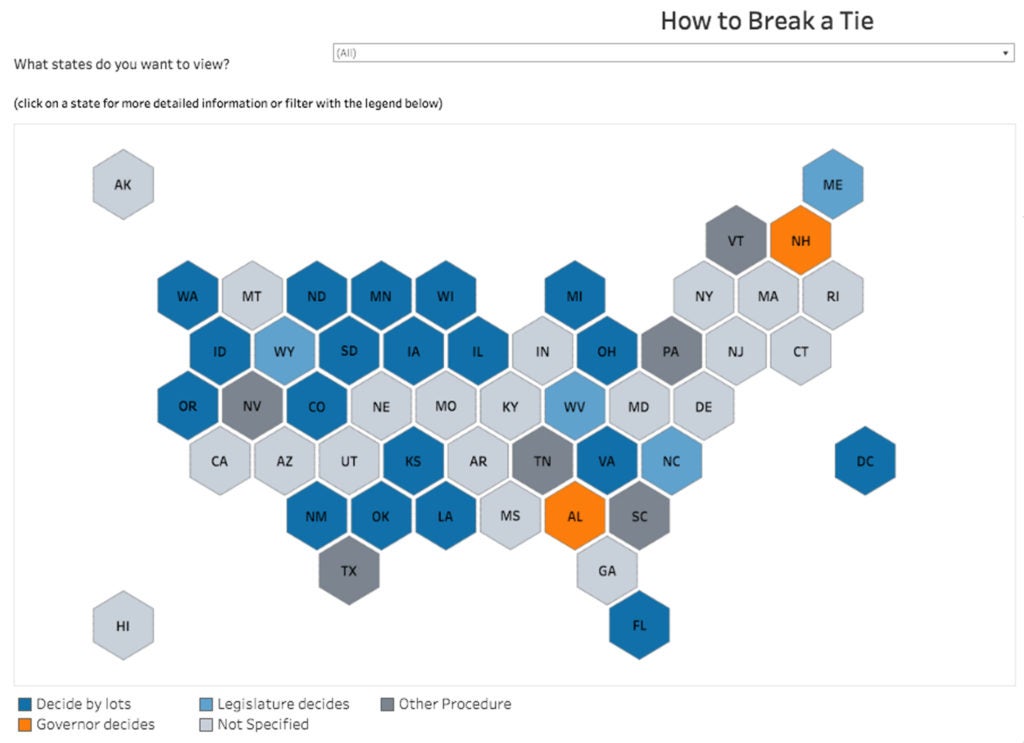

Adds student Mason Ji ’21: “All of us know that this is likely to be one of the most fiery, contentious elections we’ll see in our lifetime, and a lot of people don’t necessarily know why. They’ve heard about the red mirage, but don’t know what that is. They know it will be close in a couple of states, but don’t know how it will be contested. And people don’t realize that state legislatures and governors have a unique set of powers in election disputes. So, part of our goal is to provide possibilities for different states. We’re saying ‘Here’s a scenario to look out for, and in case it’s duplicated, here’s what we can do to remedy that’.”

“I signed up for this course because I was hearing a lot on the news about the possibility of a contested election,” says Katherine Mateo ’20, another of the students who worked on the site. She’d taken notice of a few ominous signs—including an Atlantic article, as well as President Trump’s own tweets, floating the possibility. “We came to the conclusion that the conversations we were having needed to be made public.”

Among the scenarios they discussed was that swing states would fail to reach a choice on the night of the election, and thus the decision would be shifted to state legislatures. As she points out, the president has tweeted “Must have final total on November 3rd,” alleging the possibility of mail-in fraud. “That’s one concern: that people might buy into the rhetoric that mail-in voting is dangerous, and that there is malfeasance if the vote shifts to Biden—whereas there is, in fact, a pandemic going on that has affected voting.”

It’s possible, for instance, that voting will be close in Florida. Further doubt could then be sown if, for example, a natural disaster (a hurricane or the pandemic) is deemed an obstacle to voting, or if a poll watcher alleges that particular votes were being lost or discouraged. In which case the state legislature could invoke Section 2 of the Electoral Count Act, claim that the people have failed to make a choice, and choose its own slate of electors.

“That was the eye-opener for me. I was always used to seeing my vote as a right,” Mateo says. “What the site can do is to put people on high alert. We give a textual analysis of what failure to make a choice means, we talk about how the Supreme Court could interpret it, and we make arguments around what it means for the legislature to disregard the voter choice. What the site looks to do is to point out what the open questions are, and make what we think are the best arguments.”