Early on a Thursday evening in March, 2L Gwen Hochman, a student in the upper-level course Expert Witnesses and Litigation, is poring over a series of questions she’ll be asking in just a few minutes. Dressed in a pin-striped pantsuit and looking every bit a real lawyer, Hochman is about to take her first deposition, an exercise for which she’s been preparing for weeks.

“I think it’ll be fun, but I’m really exhausted right now,” she says.

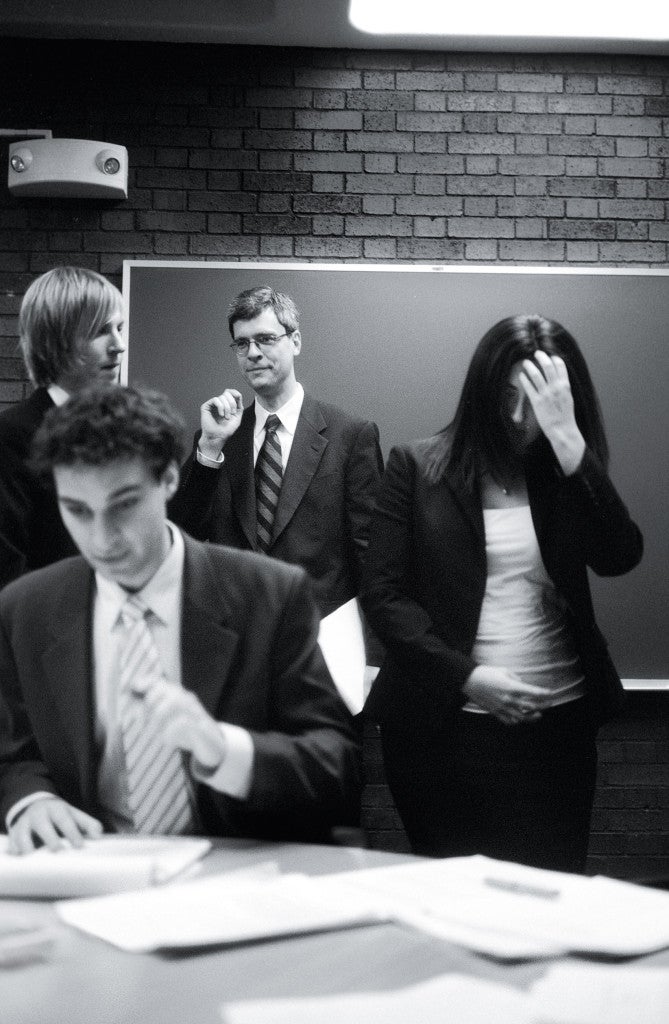

The court reporter, a student from the New England Court Reporting Institute, arrives and sets up her equipment as Hochman and her expert witness—Omar Wasow, a graduate student in the African-American studies program at Harvard—settle into chairs across a table from their opponents, 2L Dalie Jimenez and her witness, Cassandra Wolos, a graduate student in statistics.

Hochman’s weariness disappears as soon as she launches into the mock deposition. She moves quickly from setting the rules into complicated queries about statistical data related to voting patterns. Sometimes she pauses to gather her thoughts or rephrase. But both she and Wolos keep their cool.

Jim Greiner, an HLS assistant professor of law, watches carefully without interrupting. He created this unique course as a joint endeavor between HLS and the Harvard statistics department, where Greiner, who holds a Ph.D. in statistics, is an affiliate. The 13 law students will be taking and defending two depositions each, one involving a political redistricting hypothetical and the other involving an employment discrimination case. The eight statistics students, who play the roles of expert witnesses, learn to explain complicated concepts in simple terms and defend their findings against sharp challenge in an adversarial setting. The court reporting students, meanwhile, practice recording and transcribing a highly complex deposition with specialized language.

For the HLS contingent, Greiner says, this is about learning how to work effectively with clients or lawyers who have specialized knowledge of an unfamiliar field. “Modern complex litigation often comes down to a battle of the experts,” he explains. And statistical expertise, he believes, may be particularly powerful. “Scientific knowledge—of any kind—comes these days from the analysis of data,” he says, “so if law students learn something about statistics, they will have a leg up in terms of tackling any set of technical issues.”

Greiner begins the semester with a primer on relevant law and quantitative methods. He later brings in litigators and expert witnesses who’ve participated in similar cases and who discuss ethical dilemmas they’ve faced while testifying.

But throughout the course, “the fundamental premise is that there are things we can’t teach in terms of telling people how to do them,” he says. “We just have to let them do them.”

Following that principle, the students take (or defend) depositions in two cases so they can learn from the mistakes they made the first time around. “I tell the class on the first day, ‘You’re not going to communicate enough with your expert to start with, and you won’t believe that until you get to about seven or eight days before the brief is due, and you sit down to try and write it, and all of a sudden you realize you have all these questions that are unanswered.’ They all look back at me stone-faced and—I can see it in their eyes—they’re thinking, Not me, because I’m driven and this professor is just trying to encourage us to work. And I know what’s coming: When it comes to the post-deposition class, they tell me, ‘I wish I’d started earlier. I wish I’d worked with my expert more.’ And they do, in the next simulation.”