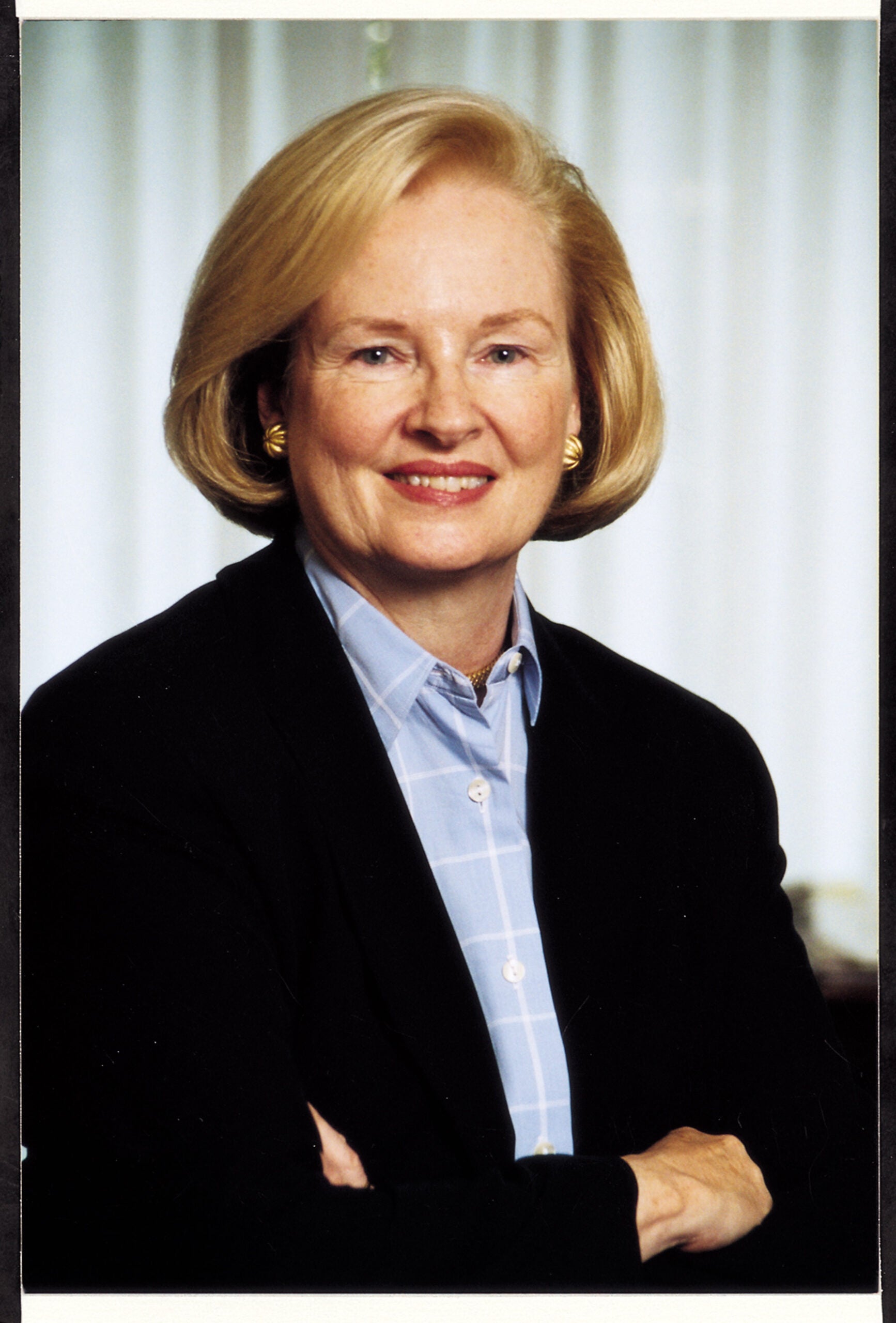

Professor Mary Ann Glendon set out to write a straightforward history of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. But Eleanor Roosevelt would not let her do it.

“It’s similar to what I’ve heard novelists describe,” Glendon said. “The characters took over the story, and Mrs. Roosevelt took over the characters–just the way she did in life.”

The result, A World Made New: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Random House, 2001), chronicles Roosevelt’s proudest achievement. After the horror of World War II, she and the other 17 members of the newly formed UN Human Rights Commission were determined to come up with a list of rights so fundamental that no country would openly disavow them.

While the delegates argued, reflected, cajoled, and edited, they saw their window of opportunity narrowing as U.S.-Soviet relations worsened by the minute. By the time the declaration was ratified in 1948, the Cold War had set in and no further progress could be made. Glendon makes it clear that one of Roosevelt’s achievements as chairwoman was her practical decision, criticized at the time, to focus on the statement of rights, rather than a binding treaty that was unlikely to be ratified by the U.S. Senate.

Glendon, who grew up in a family where the Roosevelt name was venerated, captures the pragmatic idealism of the former first lady, who brought to the commission the prestige of the Roosevelt name but also her reputation as an outspoken defender of humanitarian causes. Even today, however, the politics behind the treaty are often attacked.

When Glendon discussed her book on a radio program this spring, one caller asked why they were wasting their time with a document that had the mark of the hammer and sickle all over it. And just as often as the declaration is pegged as a socialist document, it is criticized as being too Western to be applicable to the rest of the world. These issues were present for Roosevelt and the other members of the commission, and Glendon grapples with both.

Her research has uncovered that, contrary to what some have claimed, the provisions for economic and social rights often associated with the Soviet Union were in fact supported by representatives from every country on the commission. Eleanor Roosevelt, in particular, saw them as an elaboration of her husband’s New Deal and Harry Truman’s Fair Deal. As for arguments that the declaration is Western, Glendon says she believes the document to be “impressively but imperfectly multicultural”–impressive in that people from many nations were consulted; imperfect in that people whose countries were still under colonial rule were not represented at the UN in 1948.

Today the UN Human Rights Commission itself is more multicultural. The United States, however, is missing for the first time.

In May the United States was voted off the Human Rights Commission, losing a seat President Bush reportedly considered offering to Glendon.

Glendon feels that the act goes beyond retaliation for what might be viewed as American arrogance or unilateralism. The United States was in the running against Western European countries, and Glendon says the ouster may reflect a feeling that “Europe ought to assert itself as a sort of second force.”

The real losers, she predicts, are the United Nations and victims of human rights violations. “What we have now,” she said, “is a commission that has failed to elect the United States and has accepted notorious human rights violators such as China, Sudan, and Sierra Leone. This cannot be good for people who are suffering from human rights violations around the world.”

Over the years the declaration itself has become a victim of politics, says Glendon, as “nations and interest groups continue to use selected provisions as weapons or shields.” This goes on today, she writes. Even human rights supporters treat the declaration “like a menu from which one can select what one likes and leave out the rest.” All articles, she says–those involving economic and social provisions as well as political and civil rights–were thought to be indispensable.

Yet Glendon believes that despite the misuse, the declaration is a forward-looking document whose potential has yet to be tapped.

“The Universal Declaration has become the most important point of reference for cross-cultural discussion of human freedom and dignity. It provides the framework and the terminology,” Glendon said.

Some people may think such conversations are futile. Yet without them, Glendon says, we are giving up not only on the idealism of Eleanor Roosevelt, but on the conviction–as expressed in the Federalist Papers–that human affairs need not always be governed by accident and force but can be affected by reflection and choice.